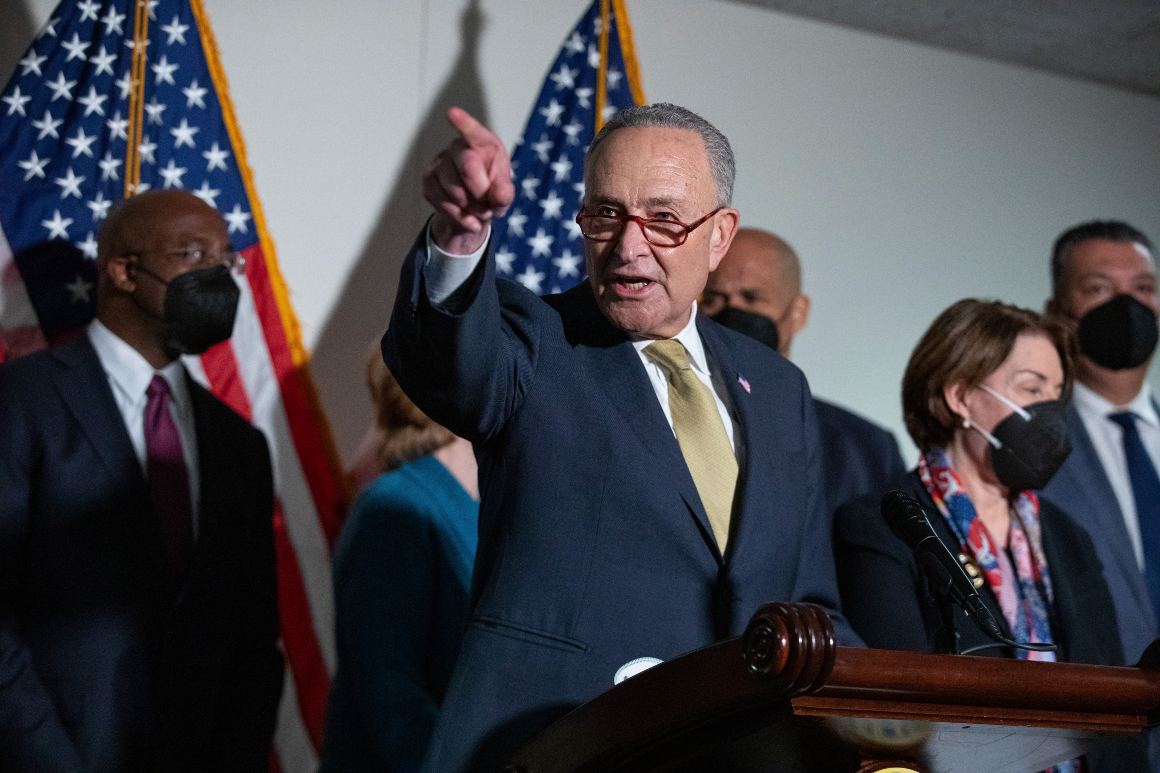

Chuck Schumer doesn’t typically lead his caucus into losing votes that divide Democrats. He made an exception for election reform.

The Senate majority leader has run a 50-50 Senate for a year now, longer than anyone else. The whole time, Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin have consistently communicated to Schumer that he wouldn’t get their votes to weaken the filibuster, no matter the underlying issue. But his decision to force the vote on the caucus anyway — and get 48 Democrats on the record for a unilateral rules change dubbed "the nuclear option" — will go down as one of Schumer’s riskiest moves as leader.

The New Yorker was a defender and wielder of the filibuster while serving as minority leader during Donald Trump’s presidency. But Democrats’ year of work on writing elections and voting legislation — and GOP opposition to an effort designed to undo state-level ballot restrictions — turned Schumer into a proponent of scrapping the Senate’s 60-vote threshold, at least for this bill.

He and most of his members have endorsed what they see as a limited change to chamber rules. Even so, Schumer has set the table for a future majority with a slightly bigger margin, whether it’s Democratic or Republican, to follow through where he fell short and perhaps go further.

Schumer gave Manchin months of space to work on a compromise elections bill, despite activists pushing him to move quicker. The leader’s insistence on a vote that will split his caucus has only trained more ire on the West Virginian and Sinema of Arizona, whom he needs to execute the rest of President Joe Biden’s agenda. Yet Schumer says he had no choice.

“We sent our best emissary to talk to the Republicans. That was Joe Manchin. And we gave him months,” Schumer said in an interview on Wednesday. “The epiphany that occurred on a rules change? He didn’t even get any bites.”

Though social spending, coronavirus relief and infrastructure have at times consumed the Senate this Congress, no topic has riveted Democrats like voting and election reform. Schumer designed Democrats’ first version of the bill “S. 1” — denoting it as the party’s top priority. Even when senators were digging into other legislation, Schumer was still maneuvering on elections, convening weekly meetings with a small group of senators for months.

His long arc of aligning Democrats for a bill designed to fight gerrymandering, expand early voting and make Election Day a federal holiday ended up persuading literally dozens of them to change the filibuster — despite previous vows in writing that they would do no such thing. In quick succession this summer, Sens. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), Angus King (I-Maine) and Tim Kaine (D-Va.) informed Schumer they would back a rules change.

That same trio tried and failed to sway Manchin to their side.

“Truly, he’s worked every way possible to try to get us to yes. This is the last piece of the puzzle. If this doesn’t do it, then he has literally turned over every rock in the crick. He’s done everything,” Tester said of Schumer.

There are no moral victories in the Senate: Bills either pass or they fail. And Schumer has repeatedly acknowledged it was a fight he might not be able to win.

Sinema and Manchin support Democrats’ election reforms but not going around the 60-vote threshold to pass them, which assures that the legislation will ultimately not succeed. Still, by midday Wednesday the rules change had won over Sens. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), all previously reluctant to chip at the filibuster.

Early last year, “maybe only half would be for changing the filibuster rule. And by the fall it grew,” Schumer said. “We have 48.”

Sinema and Manchin, however, have been remarkably consistent in opposing changes to the filibuster. In a 2019 interview, Sinema bluntly warned Schumer and Democratic leaders that they “will not get my vote” to tweak the supermajority requirement. Manchin voted against his party’s 2013 move to end the filibuster for most nominations and vowed last January that "I will not vote in this Congress” to change the threshold.

Sinema declined to comment for this story. In a floor speech on Wednesday, Manchin said Schumer should keep the voting and elections package on the Senate floor for weeks rather than move quickly to a rules change to pass the bill.

“We could have kept voting rights legislation as the pending business for the Senate today, next week, a month from now," Manchin said. "This is important.”

Just one year ago, Manchin’s and Sinema’s positions were a boon to Schumer; at that time, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to sign off on an organizing resolution for a 50-50 Senate without a vow from Schumer not to change the filibuster. Schumer never gave that promise, even as two of his moderates did.

Yet the Democratic leader has been deliberate and almost painstaking in his drive against the filibuster, to a degree that his predecessor, the late Sen. Harry Reid, was not after he left the Senate and campaigned against the supermajority requirement. Schumer convened a small group of centrist Democrats for “family conversations” about rules changes after another failed vote on voting legislation earlier last year. He made his first explicit push in December, after Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) blocked a bipartisan amendment deal on a defense bill.

At that point Schumer was most focused on passing Biden’s $1.7 trillion climate and social spending bill. When Manchin derailed that, Schumer quickly moved to the voting legislation, even while acknowledging it was an “uphill” battle.

Schumer usually touts his caucus’ unity, declining to engage in extended debates over issues that divide his 50 members. This time, Democrats were fine with isolating the holdouts.

“There’s been a lot of anxiety as to how high of a priority this is for us. And this, I think, makes it clear there is no higher priority,” said Sen. Ben Cardin (D-Md.).

Republicans view the real leftward pressure on Schumer as coming from outside the chamber.

“He’s feeling incredible pressure from his progressive base. And also, his own political future may depend on his performance, too, to avoid a difficult primary,” said Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), a frequent sparring partner of Schumer’s.

Schumer is up for reelection but has yet to draw a primary opponent, despite the GOP’s hopes that Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) challenges him. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) said it’s “extremely cynical” to believe Schumer’s actions as leader stem from a primary threat that she said won’t materialize anyway: “I doubt it.”

There are other political considerations afoot. While Republicans are planning to hammer Democratic incumbents up for reelection this fall, the four Democrats facing the toughest Senate races all back Schumer’s rules change.

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.) said Wednesday that the Senate needs to be restored “to a time where we can debate these issues,” and Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) said when she vowed to protect the filibuster she “never imagined that today’s Republican Party would fail to stand up for democracy."

Kelly said simply that Schumer’s "prerogative" is to call votes. “My job is to come here and represent my constituents in the best way I know how. And to vote on legislation, even if it’s not going to pass.”

Some Democrats suggested that Schumer’s move on Wednesday was only the start of a long campaign to peel off Manchin and Sinema. Another unilateral rules change vote this year isn’t off the table for the party.

But as Schumer neared the on-record floor vote he craved, he still sounded a note of willingness to keep working with Republicans. Even, it seems, on overhauling chamber rules.

“We have to restore the Senate,” Schumer said. “What I intend to do on rules changes is get a group together, maybe even bipartisan, to come up with rules changes and see what we can do to make the Senate better.”