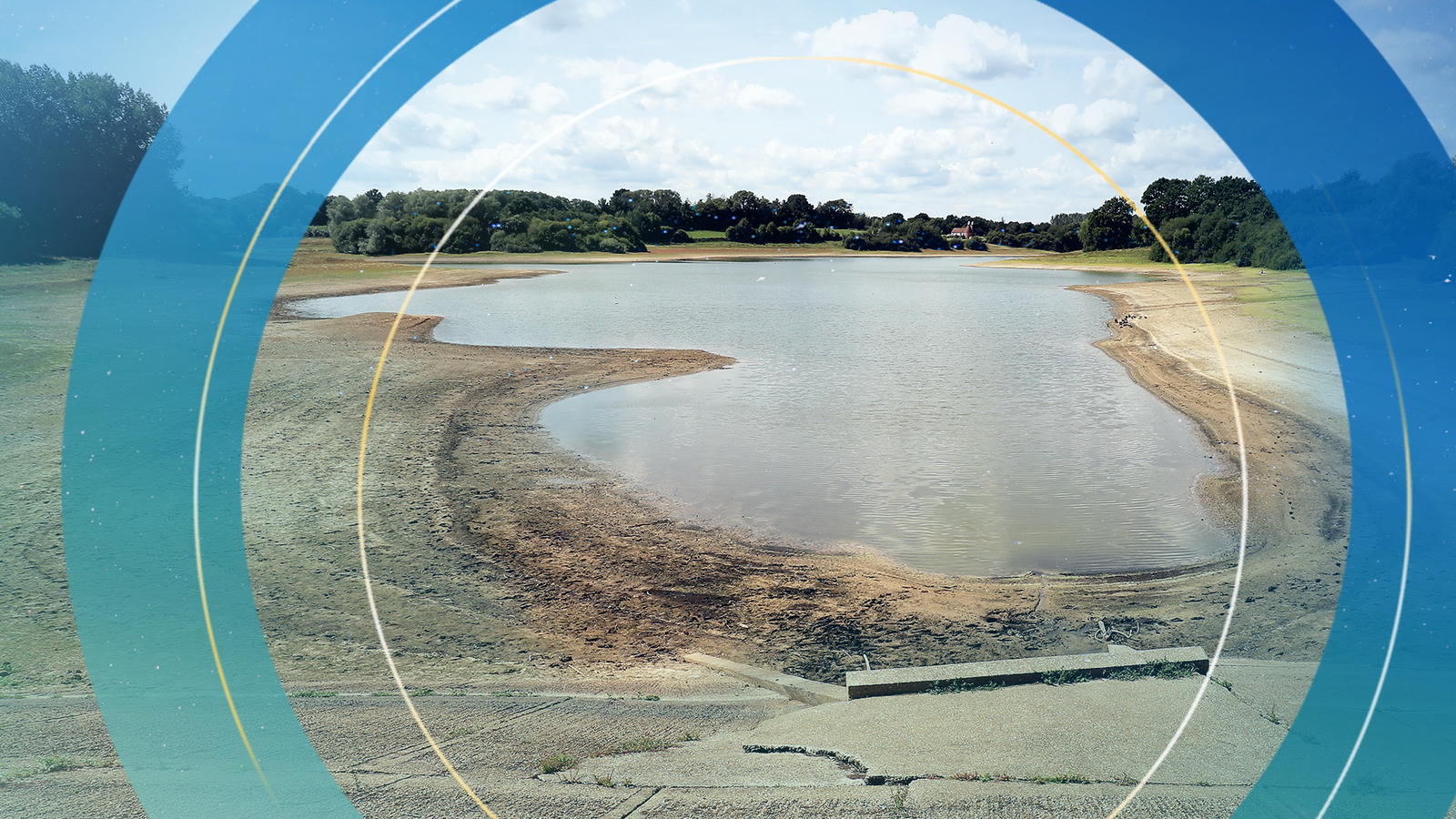

With the possibility of another warm spell in England this summer, there are warnings parts of the country could experience droughts in August.

The first heatwave and drier-than-normal conditions have already seen England’s drought level increased to the ‘prolonged dry weather stage’.

Further periods of no rain could see this pushed up even further, resulting in hosepipe bans and restrictions on commercial and residential water usage.

Following a meeting of the National Drought Group on Tuesday, the Environment Agency and water companies are urging people to be mindful with their usage to avoid shortages during hotter spells.

Here Sky News takes a look at where our water comes from and how we can help reduce our water consumption amid drought fears.

Where does our water come from?

The water we drink out of the tap originally comes from either reservoirs, rivers, lakes and springs, or underground permeable rocks that bear water known as aquifers.

In England and Wales, around two thirds of tap water comes from reservoirs, rivers and lakes (surface water) and the remaining third from aquifers.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, they use much more surface water – 97% and 94% respectively.

This is because there are more lakes and rivers there. Loch Ness, for example, contains more water than all of the rivers and lakes in England and Wales combined.

Across England, the make-up of water supply differs from region to region, depending on how much surface water there is there.

How does it get to our taps?

Seventeen water companies have signed up to the UK drought plan and are responsible for the majority of the water supply across England and Wales.

The way they collect, clean and process their water varies slightly depending on what sources they have.

But whether it comes from surface water or an aquifer it will be pumped to a treatment plant before various chemicals and materials are added to make it clean enough to drink.

First the chemical aluminium sulphate helps bind small bits of dirt in the water together to make them easier to remove later on.

Then sand and gravel are added to help remove the dirt, before ultraviolet light is used to neutralise any bacteria that could cause stomach bugs.

Chlorine is mixed in last to get rid of any remaining unwelcome substances.

Once it has been cleaned, water companies transfer it to their storage reservoirs, where it is tested regularly to make sure it is still safe, before being pumped to homes through a network of underground pipes.

Where do we use the most water at home?

The UK uses an estimated 16 billion litres of water every day across homes and businesses, according to the Energy Saving Trust.

Each person uses an average of around 150 litres a day.

At home, Britons use most of their water in the bathroom, with the shower (25%), toilet (22%) and taps (29%) taking up the majority of our consumption.

An average shower uses less water than a typically-sized bath – 60 litres vs 80 litres.

And energy efficient shower heads and units can further decrease your water usage.

In the kitchen, washing machines use the most water (9%), followed by hand washed dishes (4%) and the dishwasher (1%).

Boiling the kettle with more water than you need is one of the most common ways Britons over-use water.

Filling up a dishwasher is more water efficient than washing dishes by hand.

For those without dishwashers, using a separate bowl for dirty suds and another for cleaning them off will waste less water than rinsing them with a running tap.

Washing machines take up a considerable chunk of kitchen water use (9%), but are more water efficient if used to capacity and at a lower temperature (30 degrees or lower).

What is a drought?

Droughts are defined as “natural events which occur when a period of low rainfall creates a shortage of water”. They can be widespread across the country or just cover a small area.

The last time there was a drought in England was the summer of 2018. The most severe on record was in 1976, when water supplies were restricted, trees were destroyed by moisture stress, and dried out moor and heathlands set on fire.

The Environment Agency, which manages drought response in England, outlines three different types of drought, which affect different aspects of day-to-day life.

Environmental – This happens when river water reduces to a low level and there isn’t enough moisture in the ground, which can result in fish, wildlife and their habitats being damaged or destroyed.

At this stage, officials will limit the amount of water utility companies can take from rivers and groundwater that are suffering from low levels.

Agricultural – This occurs when there isn’t enough rain to make soil moist enough to grow crops. It also means there isn’t enough water for watering crops through spray irrigation.

At this point, water supplies to people’s homes are unlikely to be affected.

Water supply – This is the most concerning type of drought, whereby water companies struggle to supply their customers with enough water to power their homes and businesses.

They each have drought plans in place to limit customer usage and draw on emergency supplies. Often English water companies will use reservoirs in Wales in these instances – as its population is far smaller.

The Environment Agency is the body who will declare a drought and coordinate the national response with water companies.

There are four stages – normal, prolonged dry weather, drought and severe drought – with England currently sitting in the second, ‘prolonged dry weather’ one.

This means there is a short-term risk to wildlife, plants and crops, and drought plans are being enacted by water companies.

At the most severe stage, private and public water supplies would be at risk and restrictions would be imposed.

To stop this happening, water companies can impose hosepipe bans across their region and apply for drought orders, which involve reducing water pressure and setting up standpipes or water tanks for emergency supplies.