Last week Boris Johnson met representatives of the nuclear industry at 10 Downing Street to see how the technology could contribute to his Energy Security Strategy.

After the PM’s opening remarks, there must have been smiles all round when he said he wanted to see a quarter of the UKs energy coming from nuclear power.

That’s the level it was at back in the heyday of nuclear power, and would require a massive replacement programme of ageing, or already decommissioned plants.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

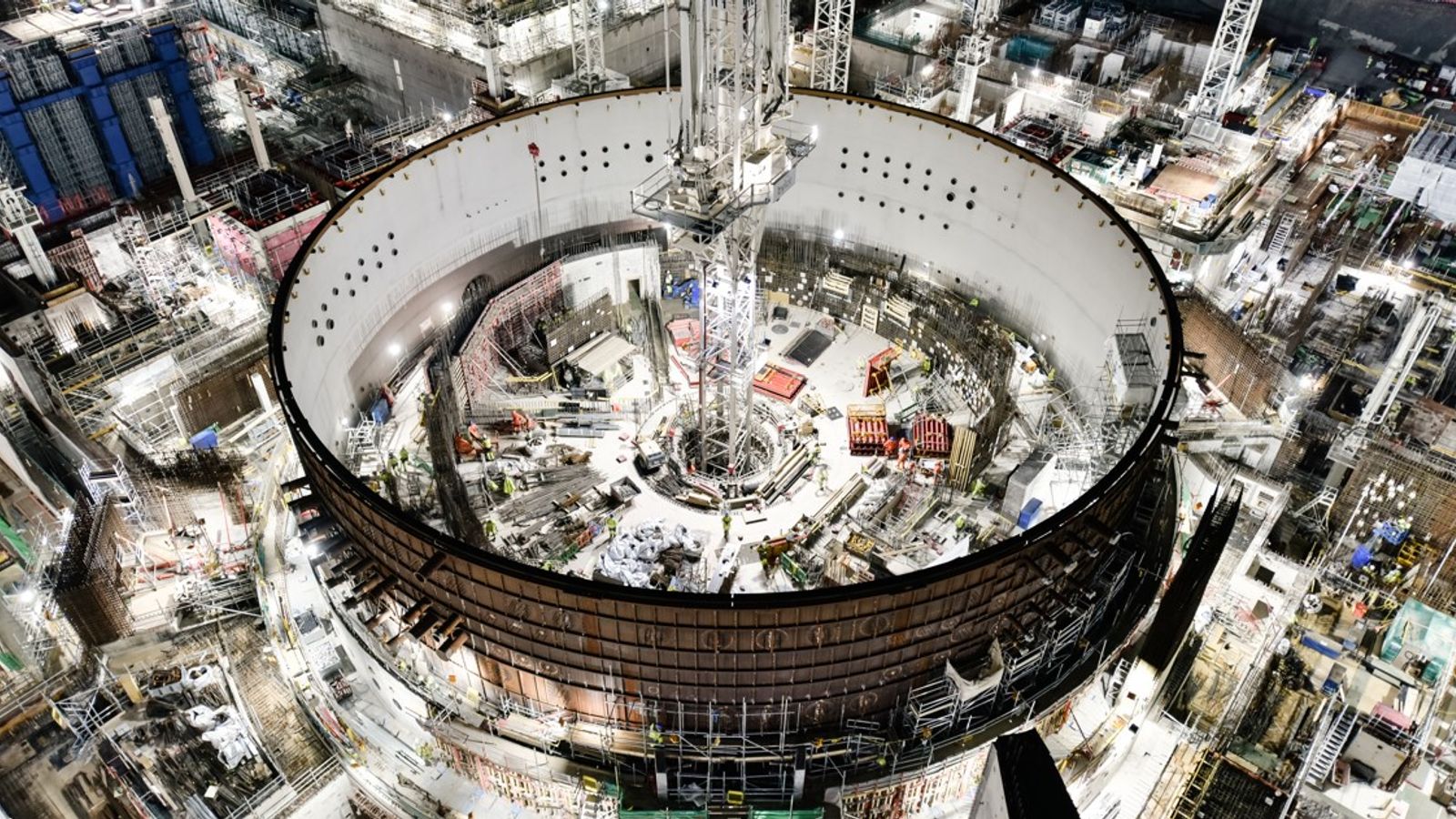

There are only six stations still operating now, making up about 16% of our electricity generating capacity. But by 2030 all but one of the existing plants are due for shut down, and there’s only one – Hinkley C in Somerset – scheduled to come online.

It’s a moment that even those in the nuclear industry thought may never come. The recent history of UK nuclear investment has not been pretty.

Two major nuclear developments in North Wales and Cumbria both collapsed during the last decade as investors pulled out following the Fukushima disaster.

And while the Hinkley Point C plant in Somerset survived, it has run spectacularly over schedule and budget.

Cash-strapped councils face steep costs for breaking off Russian energy contracts

National Grid criticised for £4.2bn sale ‘of the national silver’ to foreign investor

Energy companies ‘playing fast and loose’ as they double direct debits, Martin Lewis tells MPs

But three things have now changed the prospects of the nuclear industry.

The first is the Russian invasion of Ukraine, making energy security a new, and urgent priority for the UK.

The anticipated Energy Security Strategy is expected to feature a renewed commitment to fossil fuel free nuclear.

Then there are ambitious net-zero targets which many think aren’t achievable without nuclear power making at least some contribution.

Finally, according the industry at least, nuclear technology has improved to the extent that investing in it is far less risky.

Follow the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

And the new offering turning heads in Whitehall is the idea of Small Modular Reactors or SMRs.

The only SMR technology being actively considered here in the UK so far is being pitched by engineering giant Rolls Royce using a reactor based on the one they make for nuclear submarines.

Their idea is that reactors can be prefabricated in a factory as modules, and then assembled on old nuclear sites, exploiting their grid connections, source of cooling water, and skilled, nuclear-friendly local workforce.

By being smaller, and assembled at multiple sites around the country, they’re more “investable”, argues Rolls Royce, than colossal, bespoke reactors like EDF’s Hinkley C in Somerset.

The promise of lower cost and lower risk nuclear is likely to see SMR’s get some kind of support in the upcoming energy strategy.

But industry insiders warn that like all “first in class” designs, it might not come on stream as quickly as its backers hope.

For that reason, to ensure a quarter of our power comes from nuclear, the government will have to make sure it backs other ideas too.

That would ensure continued commitment to a new nuclear plant at Sizewell in Suffolk, and at least two new more reactors, quite likely the American AP1000 design being pitched by engineering consortium Westinghouse and Bechtel for Wylfa in North Wales and possibly other former nuclear sites.

One downside – even for small reactors – is that upfront costs are high compared to things like onshore wind and solar power.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

And with the Chancellor pushing back against the Prime Minister’s energy strategy on cost grounds – it’s unknown how much material support the industry gets.

But one thing the government’s new enthusiasm for nuclear won’t do is make a difference to energy bills in the short term.

None of these new nuclear proposals, small or otherwise, are expected to be delivering electricity to the grid for at least a decade.