The Turkish lira is seemingly in freefall.

The currency has fallen by more than 40% this year against the US dollar and, following an 11% fall on Tuesday alone, now sits at close to a record low against the greenback.

The driver for this collapse is a peculiar attempt by the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, to subvert the laws of economics.

Orthodoxy is that, if inflation rises, monetary policy is tightened to bring demand more into kilter with supply.

Mr Erdogan contends that, to the contrary, high interest rates are a cause of higher inflation rather than a way of bringing it under control.

Accordingly, the president reacted with delight when on Thursday last week, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) cut its main policy rate from 16% to 15%.

It was the third time in as many months that it had cut its main policy rate – at a time when inflation in the country is running at 20%.

Scaled-back Christmas as consumers become ‘more used to seeing fewer things on shelves’

HGV driver crisis: Drinks firms warn of Christmas booze shortage due to ‘delivery chaos’

Lidl says it will create 4,000 jobs as store numbers rise to 1,100 by end of 2025

The move came a day after Mr Erdogan promised to release Turkey from the “scourge” of high interest rates. He has called those demanding higher interest rates in the country as “opportunists” and “global financial acrobats”.

Few now believe that the CBRT is independent to set monetary policy as it wishes. It is presently on its fifth governor this decade and its fourth since 2019, Mr Erdogan having sacked the previous incumbent, Naci Agbal, in March this year after he had the temerity to raise interest rates in an attempt to tackle inflation.

His successor Sahap Kavcioglu, a former MP and business school professor, has appeared far more willing to do Mr Erdogan’s bidding. That may be, perhaps, because he is a member of the president’s ruling Justice and Development Party.

He met with Mr Erdogan following the sharp falls in the lira on Tuesday, after which, the CBRT issued a statement in which it said the sell-off in the currency was “unrealistic and completely detached” from economic fundamentals.

Simon MacAdam, senior global economist at the consultancy Capital Economics, said: “Given this backdrop and Erdogan’s record at sacking disobedient central bank governors, hopes that the CBRT will allay investors’ fears and put a floor under the lira by not cutting rates further (or even raising them) are evaporating.

“Sharp falls in the lira are likely to tighten Turkey’s financial conditions and could eventually end up straining its debt-laden banks.”

The danger is that Turkey now enters an inflationary doom loop, with the collapse of the country’s currency sparking a fresh round of inflation, if not generating hyper-inflation.

There are already signs that the economy has moved into that stage. Many Turkish consumers seeking to buy electronic products online today – such items are seen as a possible store of value in inflationary times – were unable to do so amid signs that some retailers are now unwilling either to take the risk of accepting the lira. They included Apple’s website in the country.

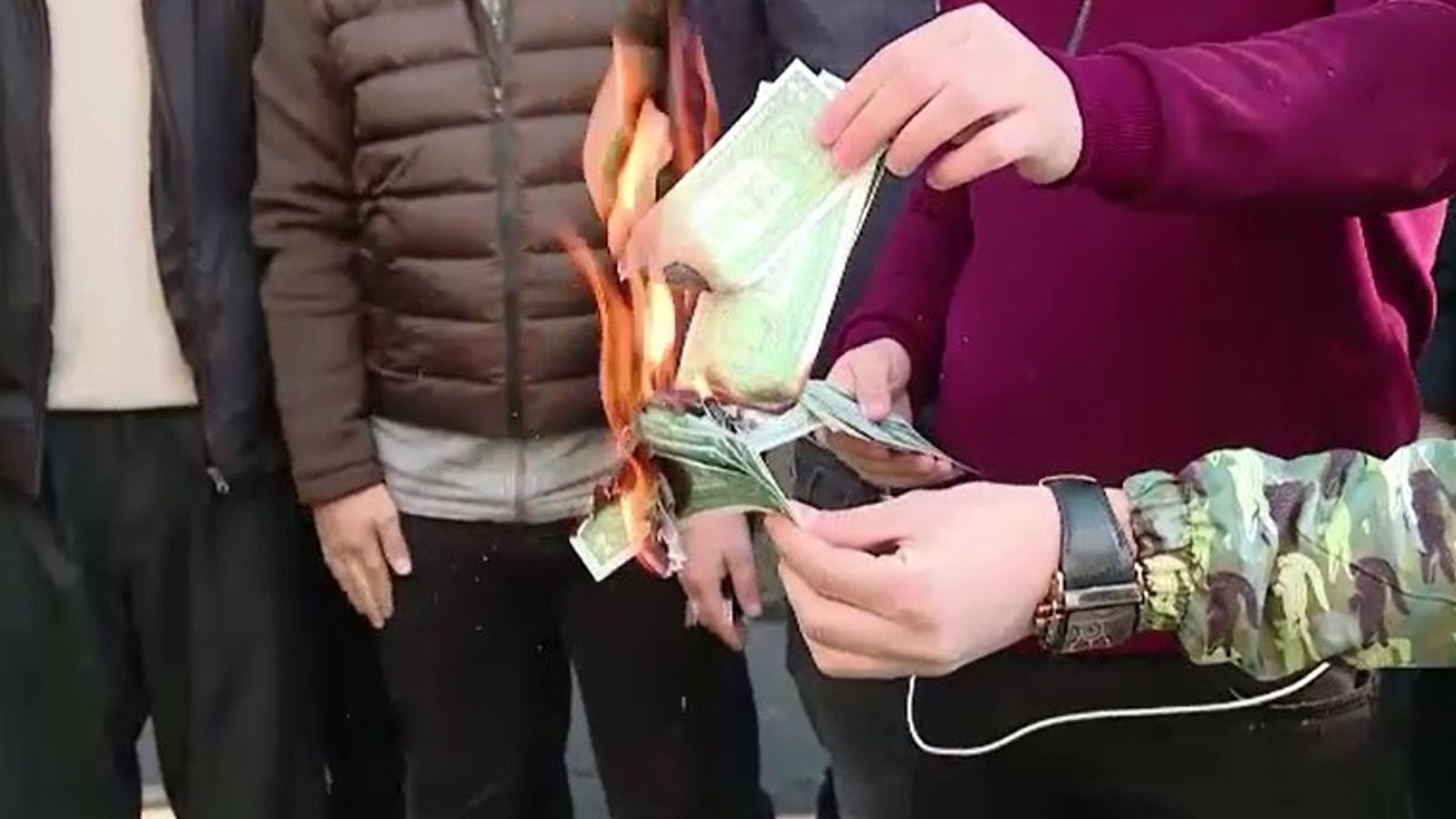

Meanwhile, with interest rates significantly below the rate of inflation, Turks have been seeking where possible to protect their spending power by offloading their holdings of their local currency in exchange for either the euro or the US dollar.

This has itself contributed to further downward pressure on the lira.

One major question is the extent to which Mr Erdogan is prepared to see the lira fall. The president has been a big advocate in the past of running trade surpluses and the collapse in the lira is certainly making the price of Turkish exports more competitive. The value of Turkish exports surged by 20%, to $21bn, in October.

This may help pacify some business leaders. Hakan Bulgurlu, chief executive of Arcelik, the owner of brands such as Beko and Grundig and one of Europe’s biggest manufacturers of household appliances, told Sky News last month that the company was benefiting from a weaker currency.

Yet that only works for businesses when all their costs, as well as their sales, are priced in a weakened currency. Turkey is heavily dependent on imports of raw materials and energy and therefore the decline in the lira is likely to bite business before long.

It is already biting consumers. The price of basic goods has been rising steadily, such as bread, which has risen by 25% in recent weeks. Bread accounts for around 2.5% of the inflationary basket on its own in Turkey and is therefore likely to contribute to a higher figure next month.

Other essential goods, including postal services, fertiliser and fuel, are also likely to exert upward pressure in inflation. That is likely to chip away at Mr Erdogan’s popularity and may in turn induce further populist policies.

While sympathetic to the plight of ordinary Turks, economists and market participants have a bigger concern, which is whether the collapse in the lira might spark a collapse in other emerging market currencies. This happened in 2018 when the likes of the South African rand, the Mexican peso and the Vietnamese dong found themselves in the crossfire.

Mr MacAdam argues this is not so much of a risk this time around because countries like South Africa do not have the same funding needs that they did three years ago and their currencies are not as over-valued.

Meanwhile, although some European banks, such as ING of the Netherlands, BBVA of Spain and BNP Paribas of France, do have exposure to the country, their exposure is not what it was, while foreign investors are also less exposed to the Turkish stock market than was once the case. There are, though, still risks ahead.

As Mr MacAdam put it: “The way this would get uglier for the rest of the world is if President Erdogan were to hold his nerve for long enough and for the lira to fall far enough to endanger Turkey’s banks.

“This could sour risk appetite enough to prompt currency falls in other emerging markets and provoke central banks, in turn, to further tighten monetary conditions.”

It is not that bad yet – but it is possible to see how things might worsen.

But for many Turkish households, already grappling with surging inflation and a real terms fall in their living standards, things are already pretty dreadful.