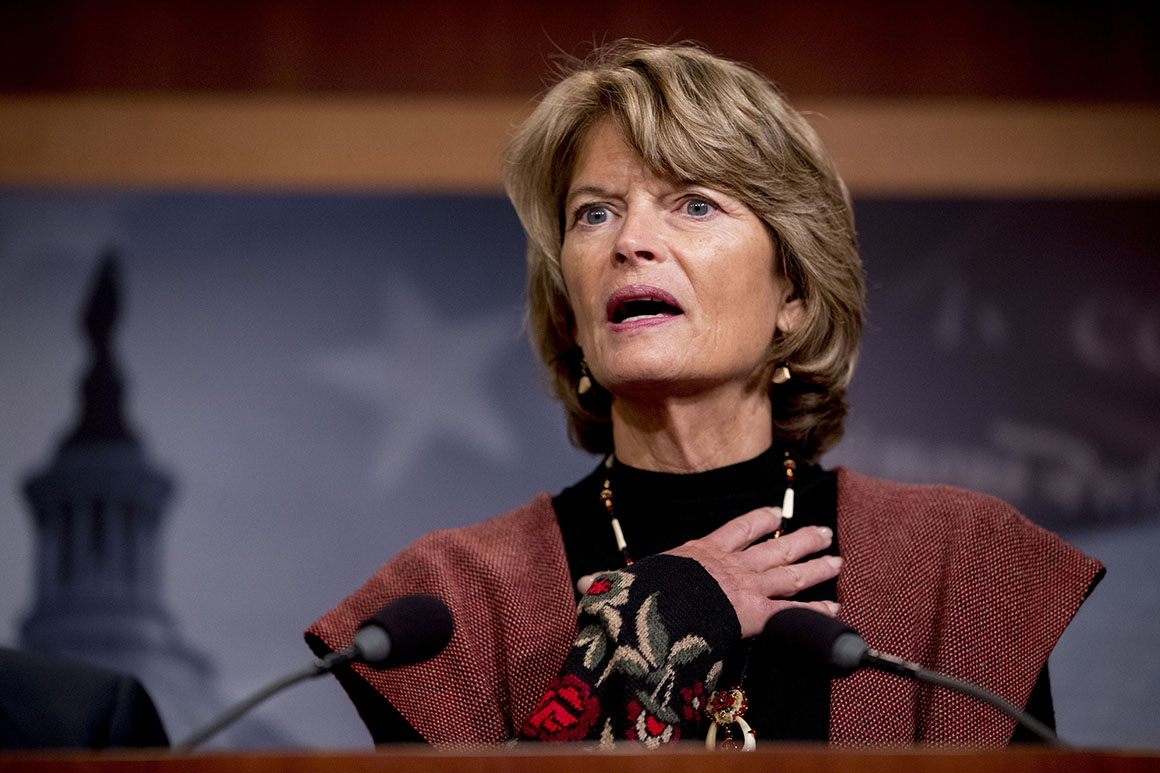

Lisa Murkowski isn’t fully comfortable with her fellow Republicans’ stance on the debt ceiling, which could risk a U.S. debt default or a government shutdown. She recognizes, however, that she’s something of a unicorn.

“I always look carefully at things that will tie or limit our ability to address things on the [government funding] side. So, I probably take a different view of it than different colleagues,” Murkowski said on Tuesday, referring to the possibility that the debt ceiling conflict causes a shutdown next week.

The moderate senator is one of a handful of Republicans who are uncomfortable — or undecided — on how to handle a bill that would avert a shutdown on Oct. 1, supply disaster relief money and lift the debt ceiling through the 2022 election. Regardless of where they come down, it’s not going to be enough to hand Democrats a lifeline: Republicans are certain to filibuster the bill once it passes the House, according to interviews with a dozen GOP senators on Tuesday.

Sens. John Kennedy and Bill Cassidy, the two Louisiana Republicans, are viewed as probable “yes” votes after their state’s Hurricane Ida experience. Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) declined to say if she’d vote to advance the bill, reiterating instead her hopes to keep the debt ceiling separate from government funding. Asked if she was undecided on how she might vote, Murkowski replied: “I’m just not telling anybody.”

But Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) is making sure that foursome stays isolated. He made the case again in a private caucus lunch meeting Tuesday that Republicans should not vote to raise the debt ceiling, going through previous debt ceiling increases and encouraging the caucus to stick together and stay strong, according to two attendees.

It’s possible another senator or two might rebel against McConnell’s hardline opposition and vote to advance the bill after it passes the House. But GOP leaders seem assured they can hold the line and block that legislation with a filibuster, refusing to allow it to come to a final vote that Democrats could then pass on their own.

That’s what occurred in 2014, when Republicans helped break a filibuster on raising the debt limit but all voted against the actual bill. That’s not happening this time, according to GOP senators.

“They are not going to get 10 Republican votes on that,” vowed Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), the No. 3 GOP leader, who helped break that impasse seven years ago.

Republicans relied on Democratic votes during the presidency of Donald Trump to lift the debt ceiling, even after their tax cuts bill passed the Senate over Democratic opposition. And counterintuitively, Republicans say they don’t want a default while saying they will vote against a debt ceiling increase.

The GOP claims times are different, pointing to Democrats’ big spending plans and ability to unilaterally pass a debt ceiling increase via budget reconciliation. However, Democratic aides say even that strategy would require some Republican help in the Budget Committee.

And help is in dwindling supply, even among the Republicans who supported Biden’s infrastructure bill just last month. Though that bill added to the deficit, McConnell said it pales in comparison to Democrats’ hopes to spend as much as $4 trillion on Biden’s agenda, some of it paid for with tax increases on corporations and the wealthy.

Infrastructure supporting Sens. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), Mitt Romney (R-Utah), Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), John Hoeven (R-N.D.), Shelley Moore Capito (R-W.Va.) and Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) all said they will vote to filibuster the debt ceiling and spending package — and they seem quite comfortable with that choice.

“I feel just as comfortable as Speaker Pelosi did in ‘19 where she said she wouldn’t vote for the debt limit unless there was an increase in spending,” Blunt said, referring to a bipartisan budget deal that also raised the debt ceiling. “The debt limit always involves some kind of negotiation on spending policy.”

Romney added: “Republicans are not going to want to vote procedurally to do this because then we become complicit and that’s not something we want to do.” Senate Budget Committee ranking member Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) said he was unsure of whether he’d even help Democrats get a new debt ceiling plan out of his committee.

If Senate Republicans hold the line next week and in the run-up to October’s potential default date, it would leave just two options: A strategic reversal by Democrats or a default. What’s more, Republicans’ debt ceiling tactics add to Democrats’ pileup of complications as they struggle to pass Biden’s jobs and families plan.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) was adamant Tuesday that McConnell is solely to blame for the brinkmanship. He declined to entertain a tactical change that would increase the debt ceiling with only Democratic votes: “It should be bipartisan.”

“You deviate from a bipartisan solution, it can cause huge problems for America now. And in the future,” Schumer said.

But some Democrats are regretting the decision to rope in Republicans. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said he’d told his colleagues he would have liked to have done the debt limit in reconciliation even though "Republicans are responsible for the debt we are voting on.” He added that it "should be bipartisan" but that he is "a little skeptical about that happening." The debt ceiling covers past spending, not future legislation that Democrats are preparing now.

Otherwise, Senate Democrats seem copacetic with that strategy. Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), who is up for reelection in a key battleground, said “we should come together in a bipartisan way to raise the debt ceiling.”

“I think we’ll get there,” said Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.). “We’ve got to do something, we’ve got to pay our debt. And I think every Republican knows the same.”

There is some recent precedent for using budget reconciliation to raise the debt limit, but it hasn’t been used since the ‘90s. And Republicans did not do it the last time they controlled the House, Senate and White House in 2018, in part because the party is generally split over whether to raise the debt limit even when they are in power.

If Democrats refuse to change course and drop the debt ceiling from their spending package, a government shutdown also becomes a real possibility next week. Democrats could drop the debt component and avoid a shutdown, but that would punt the battle over the debt ceiling deeper into the fall and closer to a fiscal cliff.

Neither side is showing any sign of backing down, and they’re both predicting someone will cave as the possibility of default becomes a reality. Democrats are betting that as the deadline gets closer, Republicans will begin to feel pressure from the business community and the necessary 10 will sign on to a debt suspension. Meanwhile, Republicans are assuming Democrats will eventually go it on their own, not wanting to be blamed for a debt default while they control Washington.

Cassidy said he’s officially undecided on how he will vote in the coming days. And Kennedy said that he will “reluctantly but likely” support the legislation because it includes disaster relief to help his state. But he has no problem with the party’s overall strategy and said Schumer is “manufacturing a crisis.”

McConnell “doesn’t often express his strong feelings about an issue in terms of how we should vote, but on this one he has been very emphatic,” Kennedy said. “He’s not going to change his mind.”