Ahead of what the British government has declared to be a Russian invasion of Ukraine, parliament was sounding the alarm about the potential impact on Britain and calling for the UK to strike back in response to any cyber attacks.

Speaking in the House of Commons yesterday Liberal Democrat MP, Jamie Stone, said: “We should be clear; if Russia invades Ukraine, massive sanctions will rightly be placed on Russia, and if that happens, we can expect a salvo of cyber attacks on the United Kingdom.”

He asked the secretary of state for defence, Ben Wallace, for reassurance about the UK’s security “and that what is good for the goose is good for the gander, and that if necessary we could use cyber warfare to give as good as we get back to Russia.”

Mr Wallace responded by mentioning the National Cyber Force, the UK’s offensive cyber agency, and added: “I cannot comment on the operations that it will undertake, but I am a soldier and I was always taught that the best part of defence is offence.”

But should the UK really expect a salvo of cyber attacks? And if the National Cyber Force responds, does that risk escalating a cyber tit-for-tat into what President Joe Biden has warned could be an actual shooting war?

UK imposing ‘immediate’ sanctions on Russia as ‘invasion begins’ – Live updares on Ukraine crisis

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

What do we know about the National Cyber Force?

The United Kingdom has adopted a much more secret approach to its offensive cyber activities than allies, including the United States which has pledged itself to a doctrine of “persistent engagement”.

The only case study that the government has ever spoken of in regards to Britain’s offensive actions references a campaign to tackle Islamic State militants and their online propaganda.

But this is a much narrower example than the range of “responsible offensive activity” described in the National Cyber Strategy.

These activities include “degrading adversary weapons systems… countering organised state disinformation campaigns… [and] preventing criminal groups from profiting from their activities”.

Read more: Cyber, war and Ukraine: What does recent history teach us to expect?

The only technical information available about how these activities are conducted is in the law describing them.

In the code of practice for Equipment Interference, as offensive hacking activities are officially known, operations require a warrant that constrains the technical aspects of the interference to what is “necessary and proportionate” as signed off by a senior judge.

These operations have to avoid causing collateral damage to individuals not covered by the warrant, something which would prevent the UK from attacking civilian infrastructure, although dual-use infrastructure with both civilian and military applications could potentially be considered a necessary and proportionate target depending on the action.

Jamie MacColl, a research fellow at RUSI (Royal United Services Institute), said Mr Wallace’s comments “reveal how little we know about the UK’s approach to offensive cyber, particularly when compared to the US”.

“Comments like this highlight how we should be having a public debate about how the government sees offensive cyber, under what conditions it will be used, and what the legal and ethical frameworks are that will guide the use of offensive cyber,” he added.

Should the UK expect a salvo of cyber attacks?

Vladimir Putin has threatened an unspecific “military-technical response” to what he described as “the aggressive line of our Western colleagues,” regarding Ukraine, and pledged to “react harshly to unfriendly steps”.

Mr MacColl added: “In the event of an invasion, Russia is going to be very focused on supporting the operational and tactical objectives of the invasion, the majority of Russia’s cyber capabilities will be tasked with that.”

But he noted warnings in the financial services industry and cautioned that the impact of sanctions – if they changed Russia’s dependence on that industry – could mean it was less of a risk to attack.

Stuart McKenzie, from cyber security company Mandiant, added: “Russia has constituted a long-standing cyber threat to the UK through means of espionage, information operations and even disruptive cyber attacks.”

“Modern warfare will see cyber used as an asymmetric tool to project power far beyond borders and the traditional battlefield. As the situation escalates, it’s likely that serious cyber incidents will not affect Ukraine alone,” he added.

“Beyond the threat of disruptive or cyber intrusions, we should also be cognisant of the threat of propaganda or influence operations, a regular feature of Russian cyber activity.

“These are increasingly used to distract, spread, or falsely leak information which is designed to change the narrative or influence opinion and could look to drive a wedge between UK, EU, NATO and the US and cause internal friction rather than a collective response.”

Read more: Russian disinformation seeking to frame Ukraine has ‘more than doubled’ in past week

Are there dangers of spill over from attacks on Ukraine?

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) said it hasn’t yet seen evidence of the UK being targeted as a result of the situation in Ukraine, but was still urging organisations to strengthen their cyber resilience.

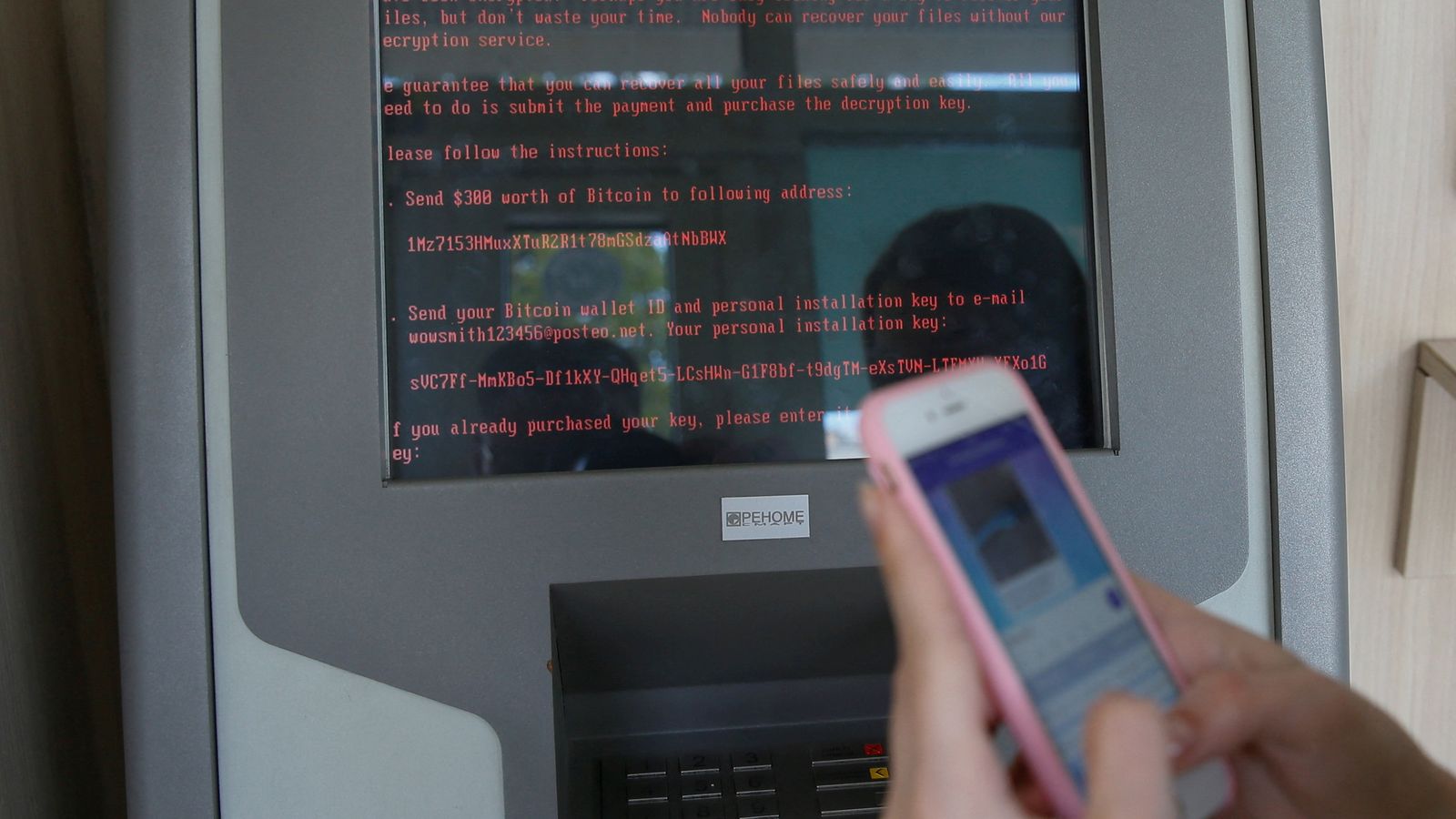

“Over several years, we’ve observed a pattern of malicious Russian behaviour in cyberspace. One big example was the ‘NotPetya’ cyber attack against Ukraine in 2017,” they said.

“NotPetya demonstrated the potential for cyber attacks to spiral out of control – and impact organisations that weren’t even intended to be hit.”

“It was created to target Ukrainian critical infrastructure. But its indiscriminate design caused it to spread further, shutting down some UK organisations’ IT systems and affecting aspects of business operations,” the NCSC added.

What is the risk of escalation?

Last year, President Joe Biden warned that if the US ended up in a “real shooting war” with a major power it could come as a result of a cyber attack.

Mr Wallace’s suggestion to parliament that “the best part of defence is offence” has prompted some concerns that the UK and Russia would trade retaliatory actions back and forth until they passed the threshold for actual armed conflict.

Speaking to Sky News, a NATO official repeated that the alliance had agreed that a serious cyber attack could trigger Article 5 – the collective defensive clause – although they said that determining whether a particular attack passed that threshold was a political decision for allies to take.

“We will not speculate on how serious a cyber attack would have to be in order to trigger a collective response,” they said, adding that a response “could include diplomatic and economic sanctions, cyber measures, or even conventional forces”.

“Whatever the response, NATO will continue to follow the principle of restraint, and act in accordance with international law,” they said.

Can cyber warfare achieve strategic objectives?

Dr Lennart Maschmeyer, a researcher at the Centre for Security Studies in ETH Zurich told Sky News that he thought escalating cyber conflict to be extremely unlikely.

“Importantly, Russia has tried to subdue Ukraine in grey zone conflict for years, using it as a test lab for cyber warfare. And yet it did not achieve its objectives,” he said.

“That is why Russia is now resorting to conventional war, and why we are unlikely to see more powerful cyber attacks now. Russia has already tried cyber warfare, and failed.

Read more on Ukraine crisis:

Russia-Ukraine: How big are their militaries?

How strong is NATO’s position in eastern Europe?

“Compared to the geopolitical consequences of a full-scale invasion, cyber conflict will not have a significant impact.”

“There is a lot of fear and hype around cyber warfare, yet my research has shown in practice cyber operations notoriously fall short of their strategic promise. Contrary to expectations, they are usually too slow, weak, or volatile to produce strategic value,” Dr Maschmeyer added.