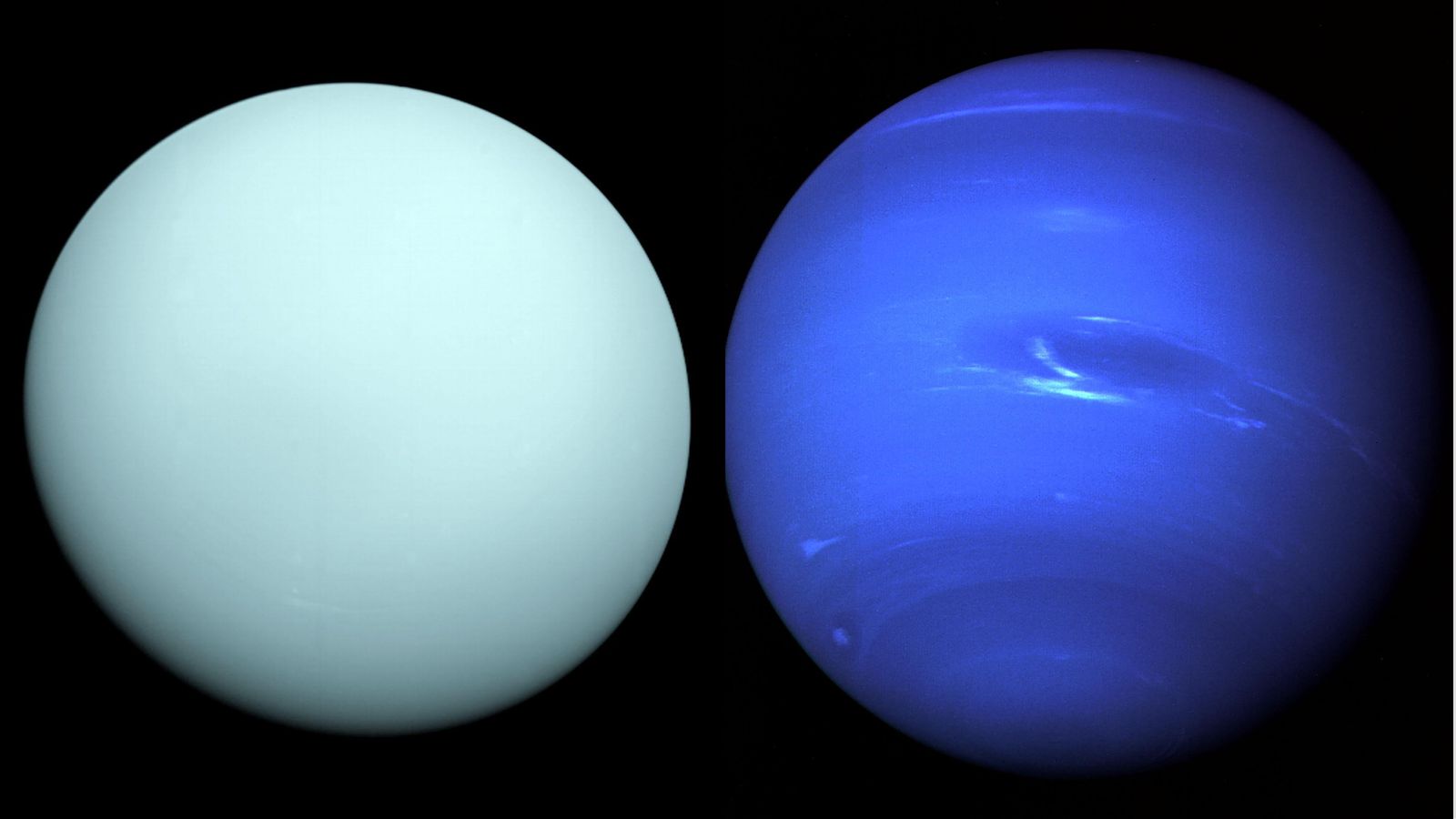

Scientists have explained why Neptune and Uranus are different colours despite having much in common.

The two furthest planets from the Sun are similar in mass, size and atmospheric composition but Neptune is distinctly bluer than its neighbour.

A new study by Oxford University has suggested the reason for this is because of a layer of haze on both planets.

Their appearances would be identical if it wasn’t for this haze, lead author Professor Patrick Irwin said.

Using observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, the NASA infrared telescope facility and the Gemini North Telescope, researchers have developed a model to describe aerosol layers in the atmosphere of both planets.

The model involves three haze layers at different heights.

On Uranus, the middle layer of haze is thicker than on Neptune, which affects the visible colour.

The Sun: ‘Solar hedgehog’ among ‘breathtaking’ images released by European Space Agency

Total lunar eclipse: Blood Moon to appear tonight in the UK – here’s when you can see it

Plants grown in lunar soil for the first time

Scientists also said methane ice condenses in the middle layer of both planets, forming a shower of methane snow that pulls the haze particles deeper into the atmosphere.

Neptune has a more active and turbulent atmosphere, suggesting it is more efficient at producing the snow which removes more of the haze and keeps Neptune’s middle layer thinner.

Therefore, Neptune appears bluer, while excess haze on Uranus builds up in the sluggish atmosphere and causes a lighter shade.

The model also showed the presence of a second, deeper layer.

Read more from Sky News:

Plants grown in lunar soil for the first time

Europe’s mission to Mars could be on hold for years

New type of stellar explosion discovered

When it gets dark, this causes dark spots on Neptune such as the famous Dark Spot GDS-89.

Professor Irwin said: “This is the first model to simultaneously fit observations of reflected sunlight from ultraviolet to near-infrared wavelengths.”

Explaining the difference in colour between the planets was an “unexpected bonus” of the model, according to co-researcher Dr Mike Wong from the University of California.