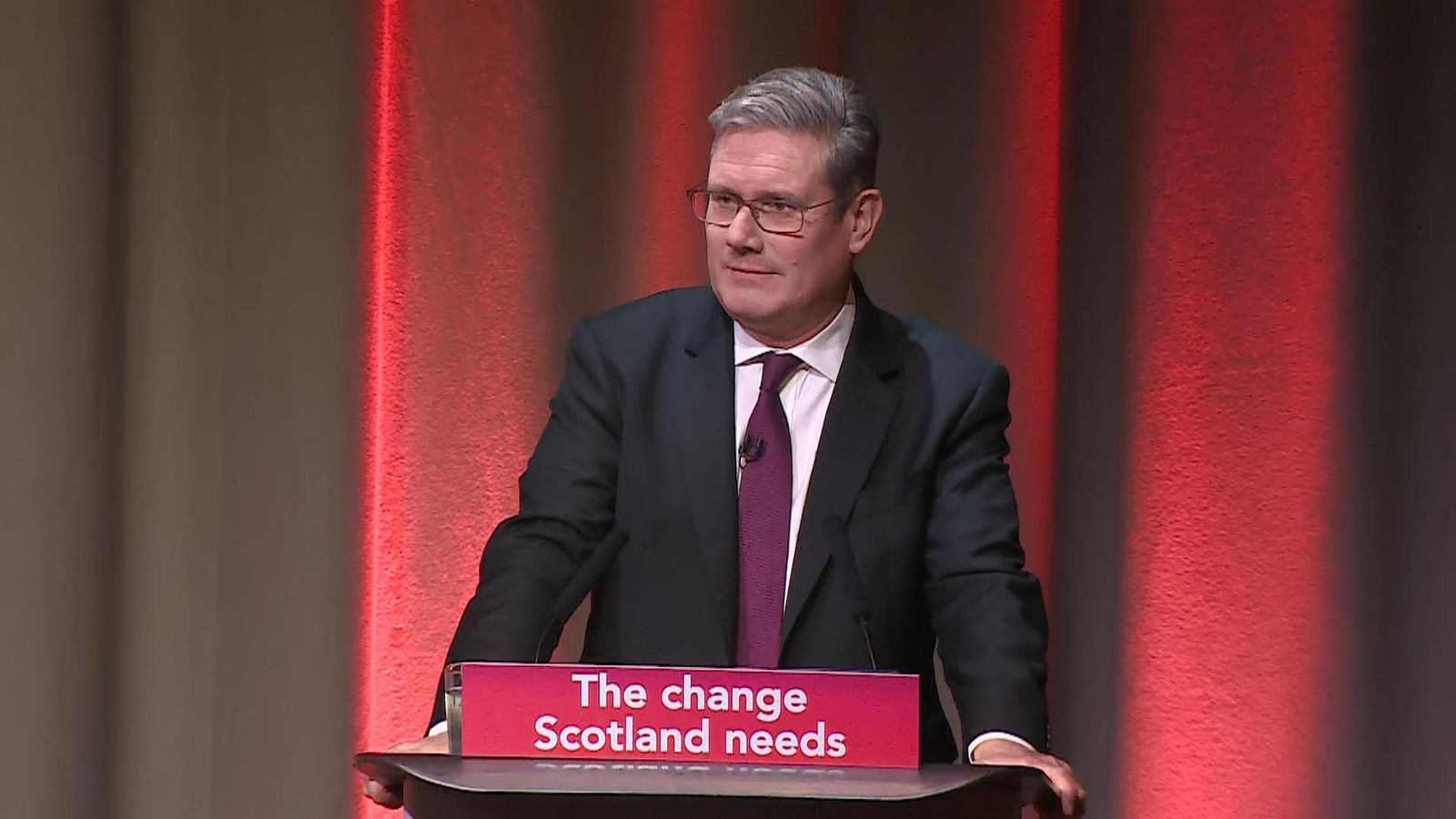

A by-election in Rutherglen and Hamilton West offers Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party the perfect opportunity to re-establish its electoral credentials in Scotland.

Overturning the SNP’s 5,000-vote majority is essential if Labour has any realistic hope of an outright win at the next general election.

The event will highlight the major fault lines that crisscross contemporary Scottish politics, divisions that also appear within political parties.

Established in 2005, Labour first lost the constituency in 2015 when the SNP, led by its new leader Nicola Sturgeon, won all but three of the country’s 59 Westminster seats. Labour’s collapse was spectacular, losing 40 of its 41 seats.

Re-gaining the Rutherglen seat in 2017, albeit by the slender majority of 265 votes, Labour might have thought its Scottish woes were behind it but the national picture was bleak.

The party, humiliated by the SNP two years before, now found itself falling behind the Conservatives in both votes and seats for the first time since 1955.

The 2019 general election added insult to Labour injury. Fewer than one in five voters in Scotland supported the party, less than half the proportion of a generation before.

Will Labour allow ‘wedge issues’ define the next election?

Thousands of criminals left prison ‘unlawfully’ over past decade, figures show

Labour attacks ‘abysmal’ figures showing just 5.7% of crimes solved last year

Voters drifted back towards the SNP both nationally and locally with Rutherglen reverting back to Margaret Ferrier, its MP until her 2017 defeat.

It is her conviction and a community service order for breaching rules during COVID that led first to her suspension from the Commons and then the recall petition that brings us to this reckoning with the electorate.

Under scrutiny will be the record of the Scottish government, with its detractors arguing that failures in public health and education are the result of Holyrood’s mismanagement, rather than failings at Westminster.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

The SNP candidate will be scrutinised about their personal loyalty towards the party’s seemingly multiple factions emerging since Nicola Sturgeon’s surprise resignation.

The subsequent police investigation and the party’s open squabbling while finding her replacement have run alongside a sharp decline in SNP support.

A 26-point SNP lead over Labour at the 2019 general election has evaporated. The five-point swing Labour requires to take this particular seat is half the rate reported by recent polls.

To avoid defeat the SNP will hope to elevate the constitutional issue of independence above other distractions. But with the prospect of a second referendum retreating, while disputes within pro-independence camps are growing, this is not going to be an easy campaign defence to manage.

There is pressure too on Labour and it must avoid at all costs the in-party squabbling over policy direction that became a characteristic of the Uxbridge post-mortem. It is not enough that Labour wins, the size of victory is of equal importance.

Its recent experience last month of the contrasts made between a massive victory in Selby & Ainsty (the second highest swing in a Conservative seat) and the failure to capture the on-paper easier target of Uxbridge & South Ruislip, shows the yardstick for judging Labour success is tough.

But there’s a good reason for that. Labour’s performance in 2019 was not just bad in Scotland. Starmer needs to out-perform Tony Blair in 1997 to enter Downing Street without the need for parliamentary support from other parties.

Blair and his Labour predecessor, Harold Wilson, owed their majorities to a phalanx of support elected from Scottish constituencies.

Read More:

Sunak’s situation is salvageable – but he’s currently on course to lose No 10

Who are the new MPs in Uxbridge and South Ruislip, Selby and Ainsty, and Somerton and Frome?

The swing towards Labour in Rutherglen & Hamilton West has to be large enough to ease the pressure on the party’s effort to secure wins in southern England.

On current boundaries a five-point swing brings 15 SNP seats into view. A less than nine-point swing sees more than twice that number of seats reverting to Labour.

Historically, these are large changes of fortune but Labour’s task will be made much easier if it squeezes the SNP on its record in government while doing the same to the Tories in regard to the Westminster version.

The omens are good for Labour. At a by-election in May 1964, five months before a general election, Labour gained the Rutherglen seat from the Conservatives with an eight-point swing.

Labour would go on to win a slim Commons majority later in the year followed by a landslide victory less than 18 months later.