It is tempting to write off the US and UK bans on Russian oil as being merely symbolic.

After all, as Kwasi Kwarteng, the UK business secretary, noted, Russian oil and oil products, such as kerosene and naphtha, only currently meet some 8% of UK demand.

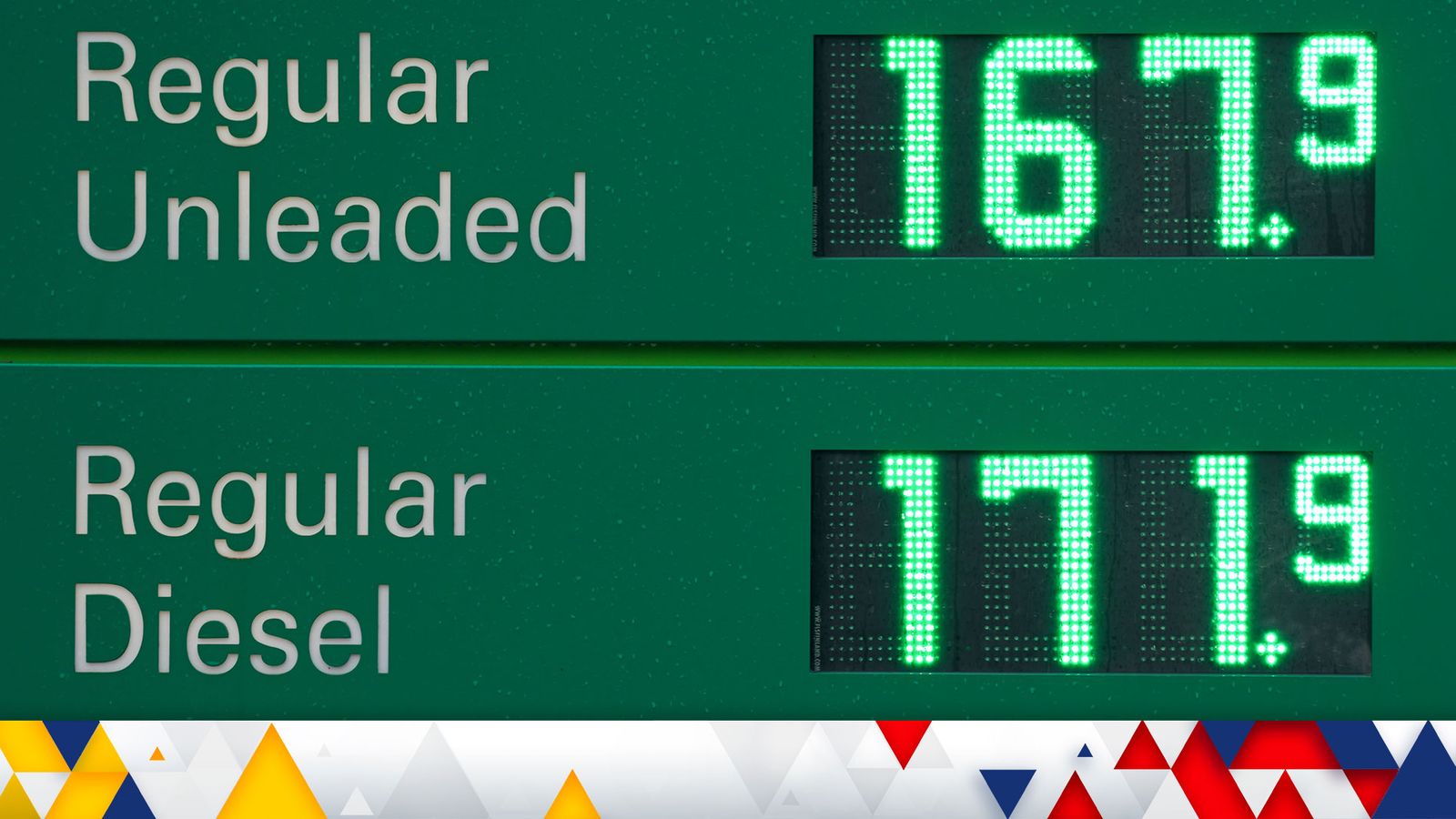

The main impact in this country, in so far as it will be felt, will be suffered by buyers of diesel – where Russia meets 18% of UK needs.

Girl, 6, ‘killed during ceasefire’ – Ukraine war live updates

This partly explains why, at garage forecourts, the price of diesel has increased more rapidly than petrol in recent days as there is already evidence of some Russian supplies not making it here.

The UK’s comparative lack of refining capacity, which many of the oil majors pared back their refining activities in recent years due to poor margins, may bite in coming weeks.

The US, meanwhile, buys just 3% of Russia’s oil exports.

Ukraine war: US bans Russian energy imports and UK will stop using Russian oil this year

Ukraine war: Shell turns its back on all Russian oil and gas and says ‘sorry’ for purchases last week

Ukraine war: Why nickel’s spectacular surge could put the brakes on carmakers’ electric plans

The loss of that business is hardly going to dent Mr Putin’s war effort.

Nonetheless, these moves send a message to the rest of the world about the determination of democracies like the US and the UK to kick away one of the main props supporting Russia’s economy.

They are intended to send a signal that, if democratic countries are serious about undermining the Putin regime, they will have to follow the lead of the US and the UK in attacking its lifeblood.

A lot of eyes will now be on Japan, a key strategic ally of the US in the Asia-Pacific region, to see whether it follows suit.

The world’s third largest economy, which has indicated it would support a ban on Russian energy exports, relies on Moscow for 4.1% of its crude and 7.2% of its natural gas.

So following the UK and the US would be a big sacrifice and particularly in view of the fact that Japan still has a significant number of businesses operating in energy intensive sectors such as steelmaking and carmaking.

It goes without saying that these sanctions would have had a lot more impact had the EU fallen into line with the US and the UK.

Without the EU, there has to be a question over the effectiveness of these sanctions.

And not just because Brussels is not – to date – intending to join in.

The US has previously reached for sanctions on a number of occasions in the past when seeking to challenge unpalatable regimes in Iran and Venezuela.

In both cases, those sanctions had some effect, although this was partly due to the ramshackle ways both those economies were being managed.

But nothing like this has been tried before on a giant petro-economy like Russia – and particularly because, unlike with previous sanctions regimes, the US is not threatening to charge businesses outside the US that continue to buy Russian crude with sanctions-busting.

The sanctions regimes against Iran and Venezuela were effective because the US could, for example, threaten to ban international banks found guilty of sanctions-busting from using the US dollar – at a stroke torpedoing their businesses.

No such threat exists for European buyers of Russian crude.

It also needs to be stressed that the UK and US bans are unlikely to result in Russian crude exports being completely phased out until the end of the year.

This is unlikely to hurt the Putin regime too much in the short term.

However, although the EU has so far failed to join the US and UK bans on Russian crude, the oil market itself appears to be self-sanctioning.

This can be shown by the consistent discount that has opened up in recent days between Brent crude, the European benchmark and Urals, the Russian equivalent.

At 5pm today, Brent crude was changing hands at $131.91 a barrel while Urals was at $111.88.

It can also be shown by the opprobrium that was heaped on Shell after it emerged that the energy giant bought a cargo of cheap Russian crude last Friday from the trading giant Trafigura – an act for which it was publicly shamed by Ukraine’s foreign minister and for which it has apologised.

The industry is already voting with its feet and Moscow is finding it increasingly difficult to identify buyers for its crude – although it will still find them in China and India.

There will naturally be concerns that the moves today from the US and the UK will drive further increases in oil and gas prices.

That does not appear to be the case and, indeed, most analysts believe the increases of recent days actually reflect the market pricing in such an action.

That is not to say there will not be consequences.

The US and the UK will have to find alternative sources of crude.

America, thanks to its shale reserves, will find that rather easier than Britain.

The chances are that the UK will have look to the North Sea in the short term and, in the longer term, towards stepping up the transition to renewables.

It may also add impetus for the need to build new nuclear generating capacity.