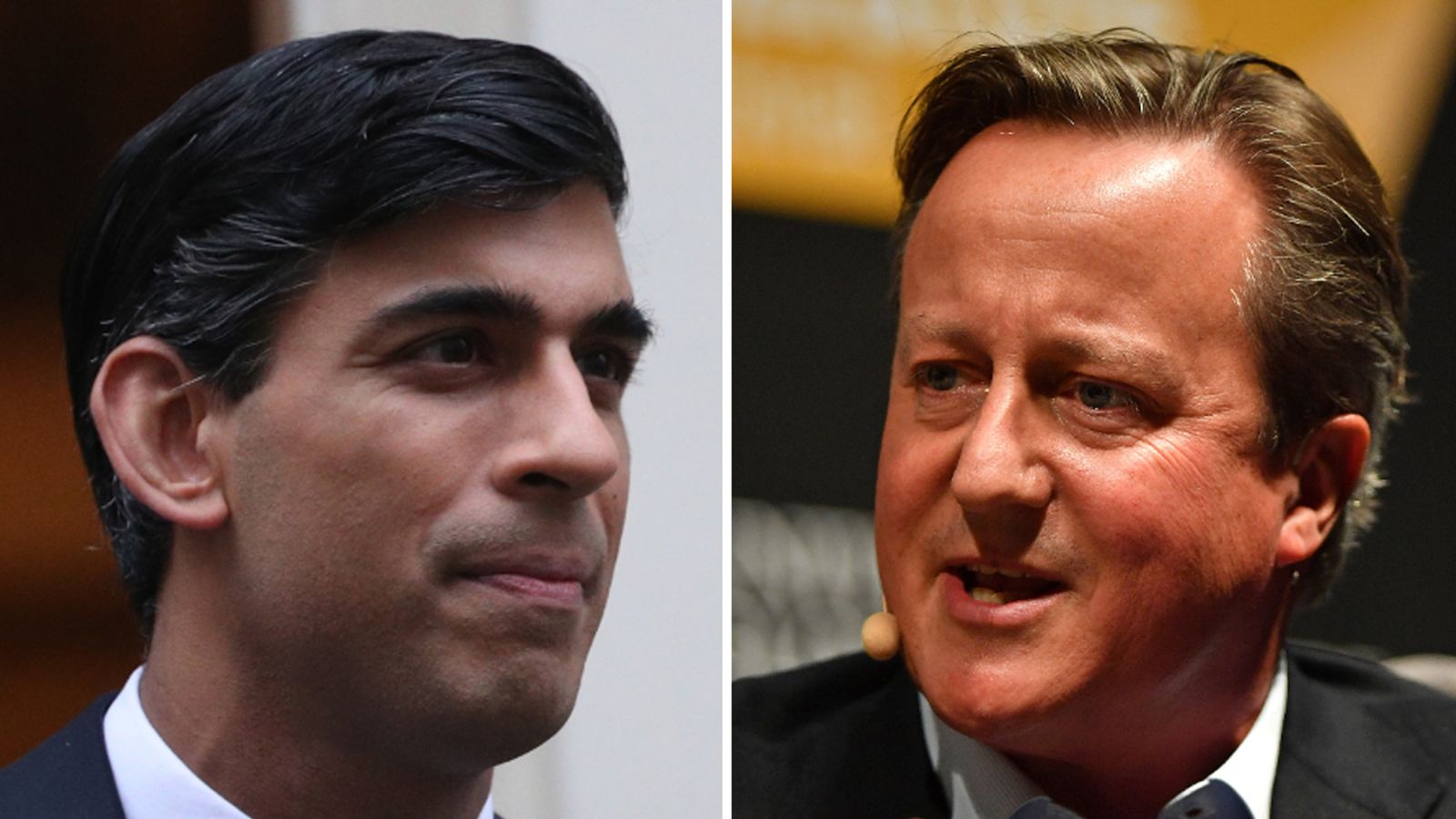

The vortex caused by the collapse of Greensill Capital has consumed the fortunes of its eponymous founder Lex, the reputation of former prime minister David Cameron and, most seriously of all, may yet do the same for Liberty Steel and the 3,000 jobs it supports.

Rishi Sunak and the Treasury officials who were the subject of Mr Cameron’s concerted, desperate lobbying efforts are determined not to join them in a trail of destruction that is already the subject of a Serious Fraud Office investigation.

After more than three hours of evidence to the Treasury Select Committee they will feel more confident they are likely to escape with barely a hair out of place.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Last spring the chancellor and his two senior civil servants, First Secretary Sir Tom Scholar and deputy Charles Roxburgh, received more than 30 messages from Mr Cameron pressing for Greensill to access a key COVID lending facility.

The former PM wanted Greensill to be accredited to one of the Government’s emergency lending schemes, the Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF). It would allow Greensill to make loans with taxpayer cash to its customers, guaranteed against “commercial paper” issued by the financial institutions taking part.

The problem for Greensill was that the terms of the scheme, set by the Bank of England, meant only investment grade companies were accepted to the scheme, and Greensill did not clear the bar.

Ultimately nothing Mr Cameron said to Mr Sunak, his officials, Michael Gove, deputy governors of the Bank of England, or anyone else he love-bombed made a difference.

That was Mr Sunak and his officials’ best and only necessary defence against MPs’ questions about why so much time was expended on Greensill, and whether a company that didn’t have a former PM with share options chasing ministers would have got as much attention.

There was no apology for indulging Mr Cameron from the chancellor, though he did admit surprise at hearing from the former PM: “I hadn’t spoken to him since he was prime minister and I was a backbench MP.”

He said in the teeth of the COVID crisis, before any of the concerns about Grensill’s underlying finances were known, any option was worth considering.

“It was entirely right that we looked at it, was worth exploring, we did the right amount of work to reach the right answer which was not to go ahead,” he said.

He went further, suggesting that the publicity and exposure the Greensill case has had could even be damaging to future policy-making, causing a “chilling effect” if companies and organisations felt their private correspondence, like Mr Cameron’s, could be made public.

While Greensill did not get access to the CCFF, it was accredited to offer loans under a different scheme, the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loans (CLBILs). These are issued by the state-owned British Business Bank (BBB) and guaranteed by the taxpayer.

Lex Greensill told the committee his company had issued around £400m in CLBILs, but Mr Sunak stressed the guarantees had been suspended because the BBB is investigating whether the company met the terms of the scheme.

That leaves the taxpayer short by around £6m of direct exposure to Greensill, the bulk of it in unpaid tax.

Mr Sunak’s version was endorsed by Sir Tom and Mr Roxburgh, both adamant they felt under no undue pressure from either the former prime minister or the current chancellor.

That despite Sir Tom receiving 23 texts in a month from Mr Cameron, some of which were signed off “love Dc”.

The pair know each other well, Mr Cameron having hired Sir Tom as an advisor during his time in Downing Street and rewarded him with a knighthood.

Sir Tom told MPs the biggest lesson of the Greensill saga was the importance of following correct processes and “keeping a proper record of all conversations”, which he was delighted to say the Treasury had adhered to in this case.

“When we went back to look at paperwork we found it all,” he said.

Not quite. Unfortunately Sir Tom could not share his responses to Cameron’s barrage of texts because last June he forgot the password to his phone and it was wiped for security reasons.

He told MPs the same thing has happened about once a year since he got his current number while working for Gordon Brown in 2008. “It tends to happen shortly after the password is changed,” he told MPs.

Sir Tom said the messages will be made available via the Treasury Freedom of Information process just as soon as Mr Cameron, who has the only other copy, has sent them to him.