Some of Britain’s best-loved 20th-century writers were denounced as drunkards, snobs and authors of extreme pornography during a search to fill the prestigious role of Poet Laureate, newly released documents have revealed.

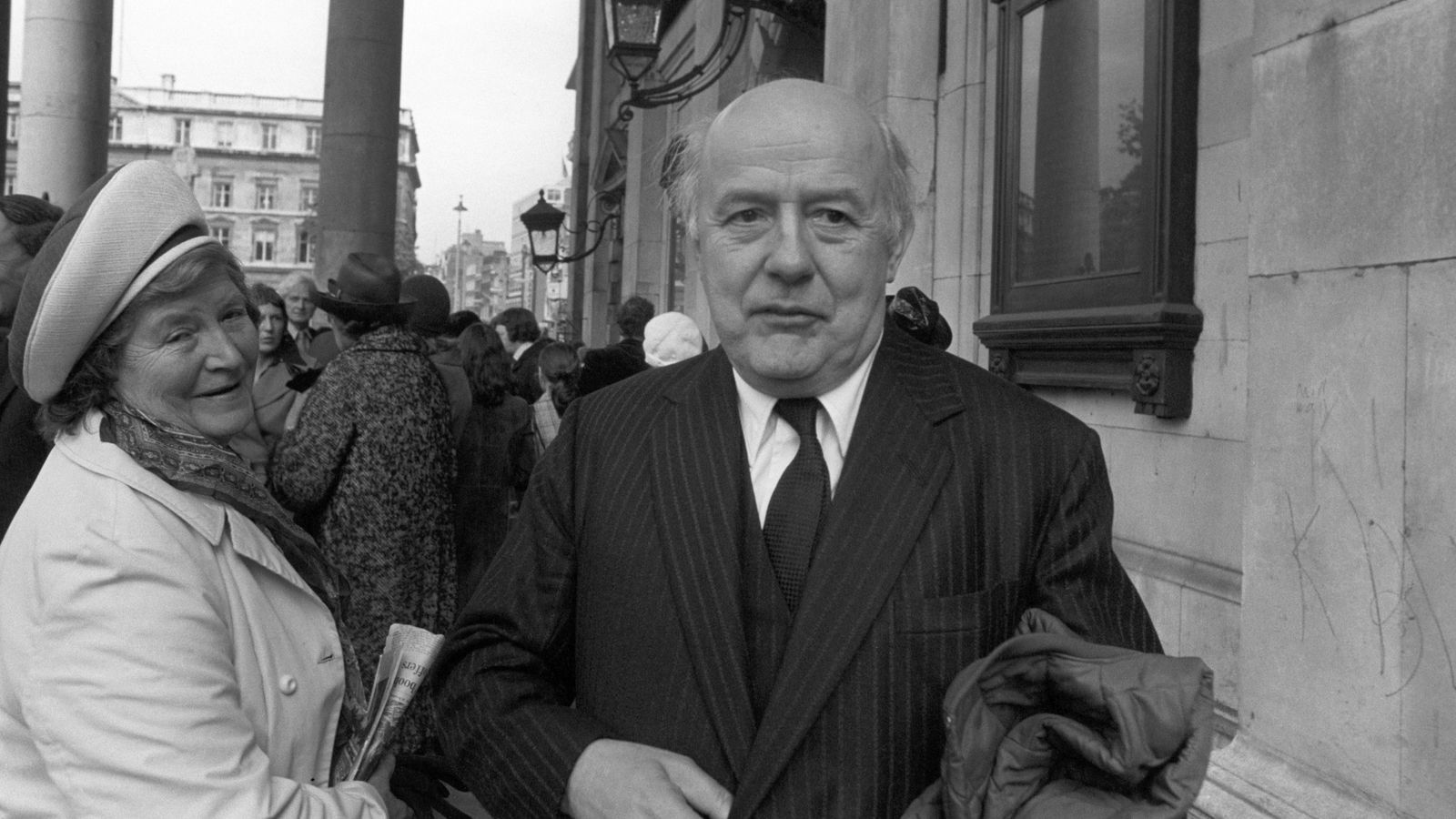

Sir John Betjeman, who famously penned the poem Slough, was initially overlooked for the honorary role because he was considered a lightweight “versifier” who lacked serious merit, according to the official files.

WH Auden and Robert Graves, regarded as the leading poets of the day, were also ruled out for the role in 1968, following the death of John Masefield.

It eventually fell to Cecil Day-Lewis, father of actor Sir Daniel Day-Lewis, who was eventually appointed by Queen Elizabeth II on the advice of then prime minister, Harrold Wilson.

Now government papers, released by the National Archives in Kew, have revealed the extraordinary infighting and backbiting behind the decision.

Following the death of Masefield, Number 10 Appointments Secretary Sir John Hewitt was tasked to take soundings on who could take on the prestigious role.

Auden and Graves were dismissed for various reasons, leaving Betjeman and Day-Lewis as the frontrunners.

But Betjeman – perhaps best-known now for his lines “Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough!/It isn’t fit for humans now” – faced opposition.

According to the papers, Lord Goodman, chairman of the Arts Council and Mr Wilson’s personal legal adviser, warned that to offer Betjeman the post “would not be to take the matter seriously”.

“The songster of tennis lawns and cathedral cloisters does not, it seems to me, make a very suitable incumbent for the poet laureateship of a new and vital world in which we hope we are living,” he wrote dismissively.

“An aroma of lavender and faint musk is really not right for an appointment of this kind at this moment.”

Day-Lewis was selected for the role, but he too faced opposition, chiefly from Geoffrey Handley-Taylor, chairman of the Poetry Society, who described him as no more than “a good administrative poet”.

He held the role for four years until his death in 1972, which sparked a new and equally bitter selection process.

Despite not being eligible for the role after moving to America and taking US citizenship at the outbreak of the Second World War, Auden was again put forward as a front-runner.

However, there was speculation that he could return to the UK and reclaim his British nationality in order to take the post.

In a letter to Number 10, Jon Stallworthy, another poet and literary critic, wrote: “For him now to turn his coat again would make a mockery of the laureateship.”

Then came accusations from Ross McWhirter, co-founder of the Guinness Book of Records.

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

According to the government papers, he contacted Sir John and accused Auden of penning a pornographic poem, named The Gobble, which had appeared anonymously in a publication called Suck. The first Europe Sex Paper No 1.

“He then produced a copy of the paper and showed me the poem by ‘WH Auden’ which ran to about 30 verses of an utterly revolting character,” Sir John wrote.

Read more:

Hollywood stars strike outside Netflix and Disney

Renowned British novelist Martin Amis dies

“His concern was that, if Mr Auden were appointed to the position, a further publication of this poem would take place and that this would bring disgrace upon the appointment itself and would reflect upon Her Majesty The Queen.”

Leonard Clark – a former HM Inspector of Schools and an outside contender for the post – also weighed into the contest.

In a series of letters to Sir John, he warned that Ted Hughes was “unsuitable”, having written “too much in a violent strain”, while Stephen Spender had become a “non-poet”.

Graves, he wrote, was too old and “wedded to Majorca”, where he spent much of the latter years of his life.

Meanwhile, Sir John wrote to Wilson appearing to dismiss Adrian Mitchell, a passionate supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and someone he said had put on a “vulgar display at Southwark Cathedral when you were there”.

Betjeman was later given the role, with Sir admitting that his previous dismissal as “just a versifier” was unfair.

“A fairer criticism would, I think, be to say that Betjeman is by no means the most eminent English poet, although he may be the best candidate for the poet laureateship at this stage,” he told Mr Heath, finally clearing the way for his appointment.