Babies from black, Asian and ethnically diverse backgrounds could be being put at risk due to a decades-old test, a new reported has suggested.

The report, from the NHS Race and Health Observatory said that the Apgar test – which assesses the health of a minutes-old baby – is not fit for purpose as it is “mainly based on white European babies”.

It follows a separate report from the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), that suggests a lack of staff, increasing obesity levels and women having babies when they are older, is putting pressure on maternity care.

The Apgar test – created in 1952 by obstetric anaesthetist Virginia Apgar – is conducted in the first 10 minutes after birth.

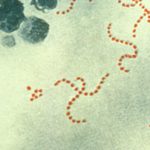

One of the categories under which babies are assessed is their appearance. To score highly, the baby is examined to see if they are “pink all over”.

Among the assessment criteria are words like “pink”, “blue” or “pale” when describing a baby’s skin colour.

The test has been criticised over its ability to accurately assess the health of babies from ethnically diverse communities.

Under a new review, conducted by experts at Sheffield Hallam University for the observatory, much of the current guidance for healthcare workers was found to not differentiate between babies from different backgrounds.

Dr Habib Naqvi, chief executive of the NHS Race and Health Observatory, said: “The results from this initial review highlight the bias that can be inherent in healthcare interventions and assessments and lead to inaccurate assessments, late diagnosis and poorer outcomes for diverse communities.”

Among the conditions that staff lack training to help them spot are jaundice – a condition where there is too much of a chemical called bilirubin in the blood – and cyanosis – when a baby does not have enough oxygen in the blood.

Healthcare workers typically look at a baby for visual clues, such as a “yellowing of the skin” for jaundice, but the report suggests devices that can accurately detect these diseases should be used instead.

Dr Naqvi added: “We need to address the limitations in visual examinations of newborns, such as Apgar scores, where the assessment of skin colour can potentially disadvantage black, Asian and ethnic minority babies with darker skin.”

Meanwhile, “stark and sobering” safety concerns in maternity services are directly linked to a lack of staff, a report by the RCM has suggested.

It said the NHS in England is short of the equivalent of 2,500 full-time midwives after only 247 new midwives entered the NHS between December 2019 and March 2023.

It means that the number of midwives increased by just 1.1%, compared to the NHS workforce in England overall rising by 14.1% in that period.

The RCM also said that women giving birth later in life and rising levels of obesity are placing even more demand on midwives, as both patients and babies require more complex care.

During November 2022, one in four women were reported to have been obese at the time of their booking-in appointment – up from 18% five years earlier.

Birte Harlev-Lam, executive director midwife at the RCM, said: “Women and maternity staff deserve nothing less than total commitment from the government to once and for all end this crisis.

Click to subscribe to the Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

“This means giving maternity services the resources needed now, and long into the future.”

The Department for Health and Social Care said the NHS was “one of the safest places to give birth in the world” but “maternity care must be of the same high standard for everyone”.

It said it has provided £165m of additional investment per year to “grow the maternity workforce and improve neonatal services”.

The Maternity Disparities Taskforce and the NHS’s first ever Long Term Workforce Plan, have both been launched to meet the challenges of an ageing and diverse population, the department added.