UK scientists are developing a COVID vaccine with an in-built insurance against mutations in the virus.

The jab, being developed at the University of Nottingham, should still be effective even if a new variant evolves that knocks out other vaccines.

The prototype has already passed pre-clinical tests and will start trials in volunteers within weeks.

Professor Lindy Durrant, an immunologist at the university and head of the spin-off company ScanCell, said the next generation of vaccines needs to be better prepared to tackle the virus as it “learns” to evade the immune system.

“What has happened was predictable,” she exclusively told Sky News.

“We have the advantage of learning from the inadequacies of the first generation of vaccines to make the second generation better.”

The three vaccines currently in use are all based on the genetic sequence of the spike protein, which the virus uses to latch onto human cells.

But mutations in the spike protein have emerged that have allowed new variants to spread rapidly in the UK, South Africa and Brazil. They may make existing vaccines less effective.

The Nottingham vaccine includes the spike protein, but also part of the “nucleocapsid” protein, a sheath that envelopes and protects the virus’s genetic material. It mutates at a much slower rate.

“It doubles the chances you win over the virus,” Prof Durrant said.

“The chances both will mutate at the same time is unlikely.”

Animal studies show the nucleocapsid protein triggers a strong T-cell response, a separate arm of the immune system to antibodies.

Prof Durrant said: “We are getting as good, if not better, antibody levels than other [vaccines], and more, and better T-cell responses.

“But that is in animals and we need to move into humans to see if it performs as well.”

The vaccine is due to start early-stage clinical trials later this spring, funded by Innovate UK.

Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Vaccine developers are having to face up to the rapidly evolving virus.

Moderna, which will start delivering 17 million doses of its vaccine to the UK in April, is already testing an updated version against the South African variant. Other companies are expected to do the same.

Because they are only tweaking existing jabs it is likely that only small-scale tests will be required. But it would still take around three months before reformulated vaccines could be manufactured at scale, and distributed.

In the meantime there is a risk that if any new variant spreads rapidly, populations would be vulnerable.

Danny Altmann, professor of immunology at Imperial College London, said it may be wise to “hedge your bets”.

“What we’re talking about here is an arms race between the immune system and the virus. Which can move better and faster to win the battle?” he said.

“I can see the logic [to the Nottingham vaccine]. Our lab has seen evidence that the immune system sees many different parts of the virus and makes a response to the protein they are looking at.

“What we don’t know is how much extra that brings to the party.”

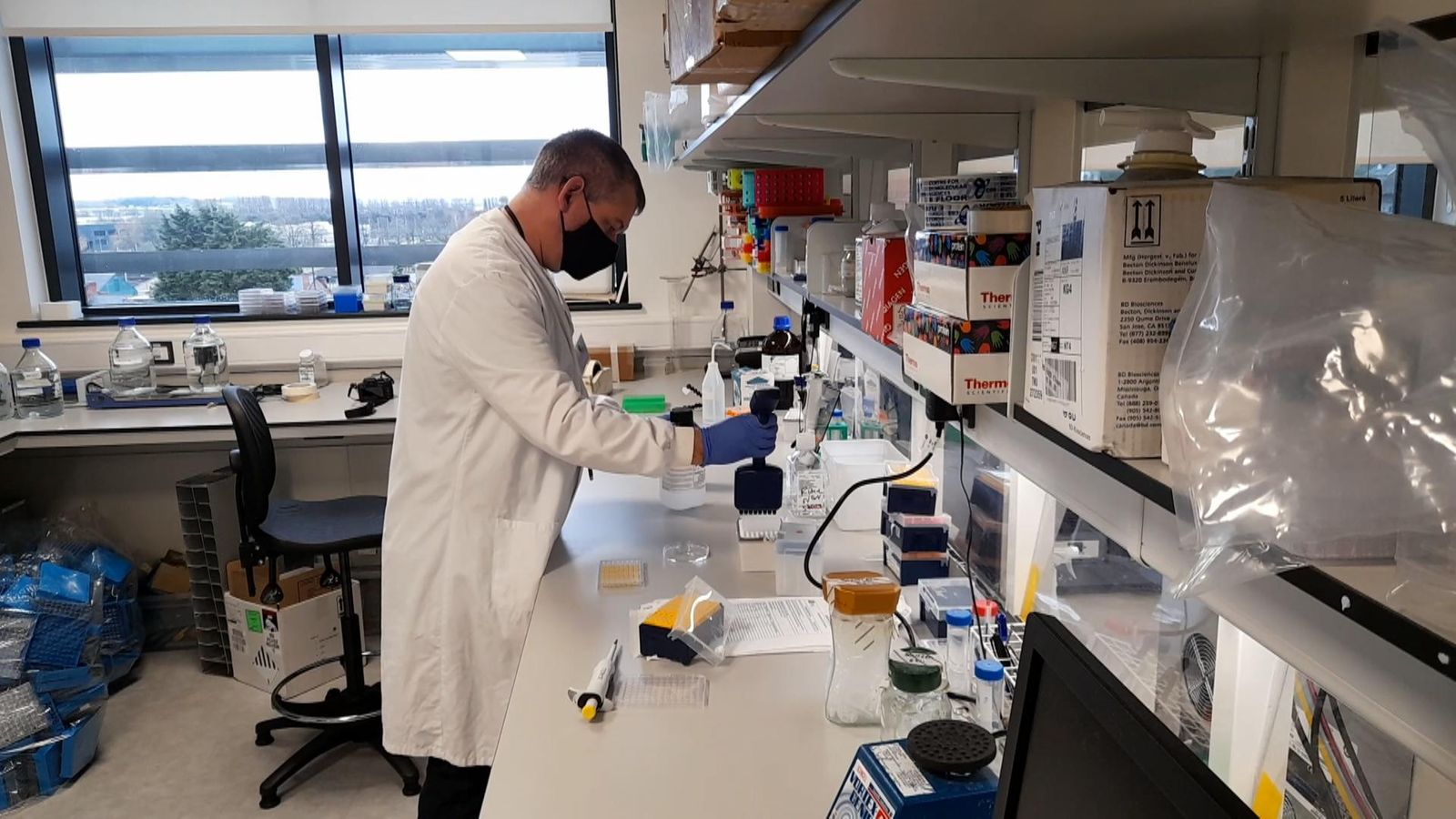

The Staffordshire-based company Cobra Biologics is already producing batches of the Nottingham vaccine to test production and prepare for the trials.

Alexandra Brownfield, the company’s business development director, said the vaccine is “grown” inside cells in a bio-reactor. Just 50 litres of a soup of cells and nutrients can produce “a few thousand doses” over four to six weeks.

She said producing the first batch of vaccine is a thrill: “It’s a really good feeling, but we are always thinking about the next batch.

“It’s a high-pressure environment, so although it’s a relief we’re then thinking we’ve still got work to do with the next batch.”