New research is shedding light on the differences between how human and Neanderthal infants developed after birth.

Scientists at the University of Kent’s school of anthropology believe that modern human children may develop over a much slower and extended period compared to the now extinct species or subspecies of human.

Using state-of-the-art technology to examine the milk teeth of Neanderthals that lived as recently as 120,000 years ago, the researchers found evidence that they sprouted quite early.

Anthropologists know very little about what life was like for Neanderthal infants in the months before and just after their birth.

But the new study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, based on the milk teeth of three Neanderthals, offers some insights.

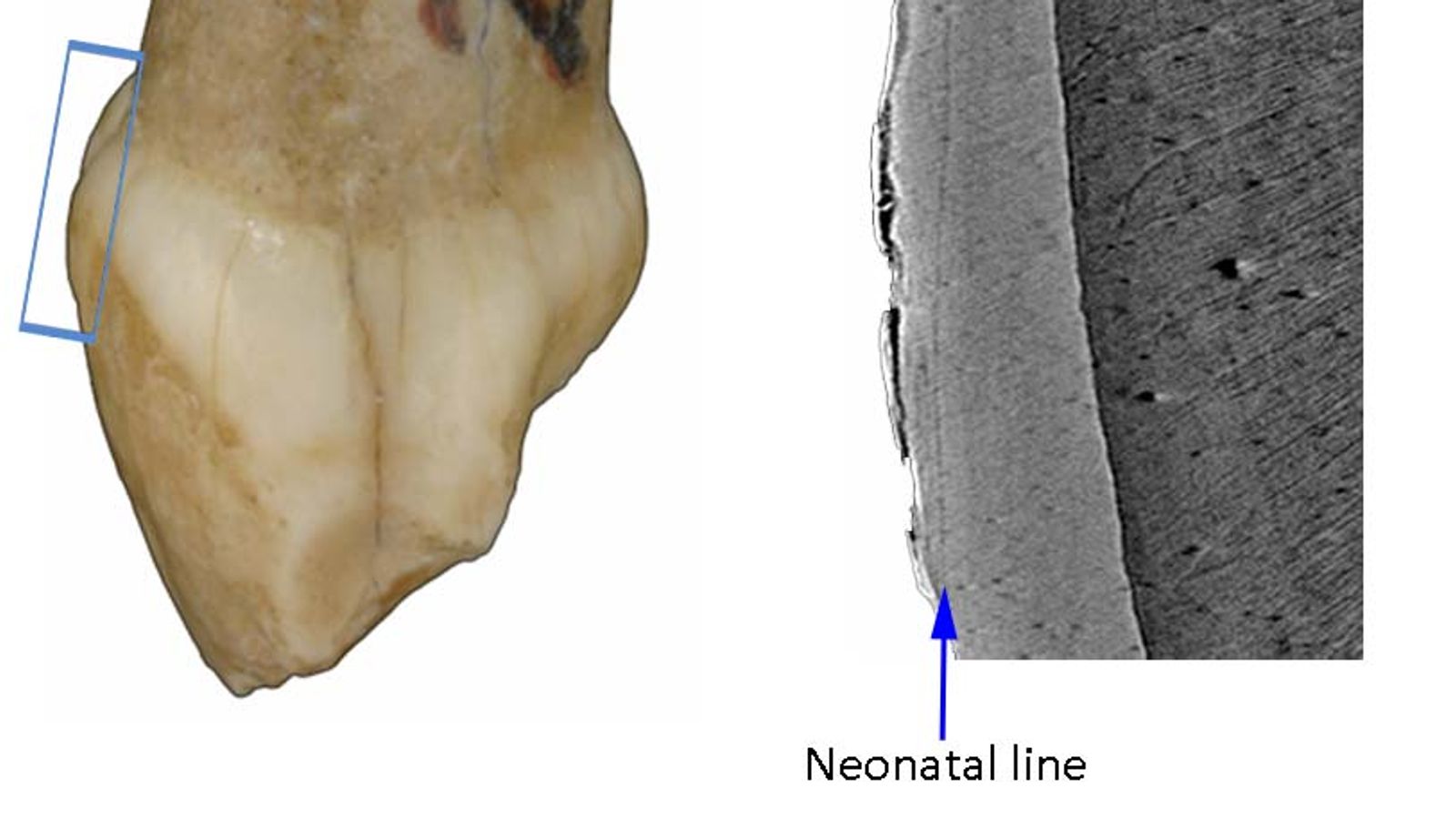

Milk teeth are helpful for scientists because they start to form before an infant is born and then continue to develop as part of a growing organism.

Because of the way the body puts down layers of enamel, milk teeth effectively retain a record of their own growth which preserves quite well as fossils.

NASA Dart spacecraft: Space agency launches first ever asteroid deflection mission

NASA mission or no, thousands of people could still be killed by a completely unpredictable asteroid impact

Apple sues spyware company NSO Group over alleged iPhone hacking

Dr Alessia Nova explained: “We used state-of-the-art non-destructive virtual histology that relies upon synchrotron radiation to examine the inside of the milk teeth. We were able to identify the exact moment these Neanderthals were born.”

Her colleague Dr Patrick Mahoney added: “Our study has revealed these Neanderthals had an accelerated pattern of dental development compared to a typical modern human child. This likely enabled them to process more demanding supplementary foods at an earlier age compared to a typical modern human child.”

These findings are consistent with other studies that had suggested Neanderthals had high brain growth rates by their second year which probably generated large energetic costs.

According to the team at Kent, these costs “could have been offset for Neanderthal infants by their ability to process more demanding supplementary foods at a relatively early age, thereby providing the increased energy rapid brain growth demanded”.