Moments before the Senate took a pivotal vote on its bipartisan infrastructure deal, negotiators zeroed in on the most important undecided member: Mitch McConnell.

The Senate minority leader stayed quiet for weeks but finally tipped his hand on Wednesday afternoon on the floor to a bipartisan group of colleagues, according to senators and aides. He told them he would support moving ahead on the bill, provided that the legislation coming to a final vote was their agreement — not something written by Senate Democrats.

It was the first inkling, among even McConnell’s closest allies, that the Kentucky Republican would support one of President Joe Biden’s top priorities: a bipartisan effort to plow $550 billion in new spending to roads, bridges, public transit and broadband. No senator in McConnell’s inner circle knew that he was about to take the plunge until moments before the vote, and some didn’t know until McConnell broke the news on Twitter.

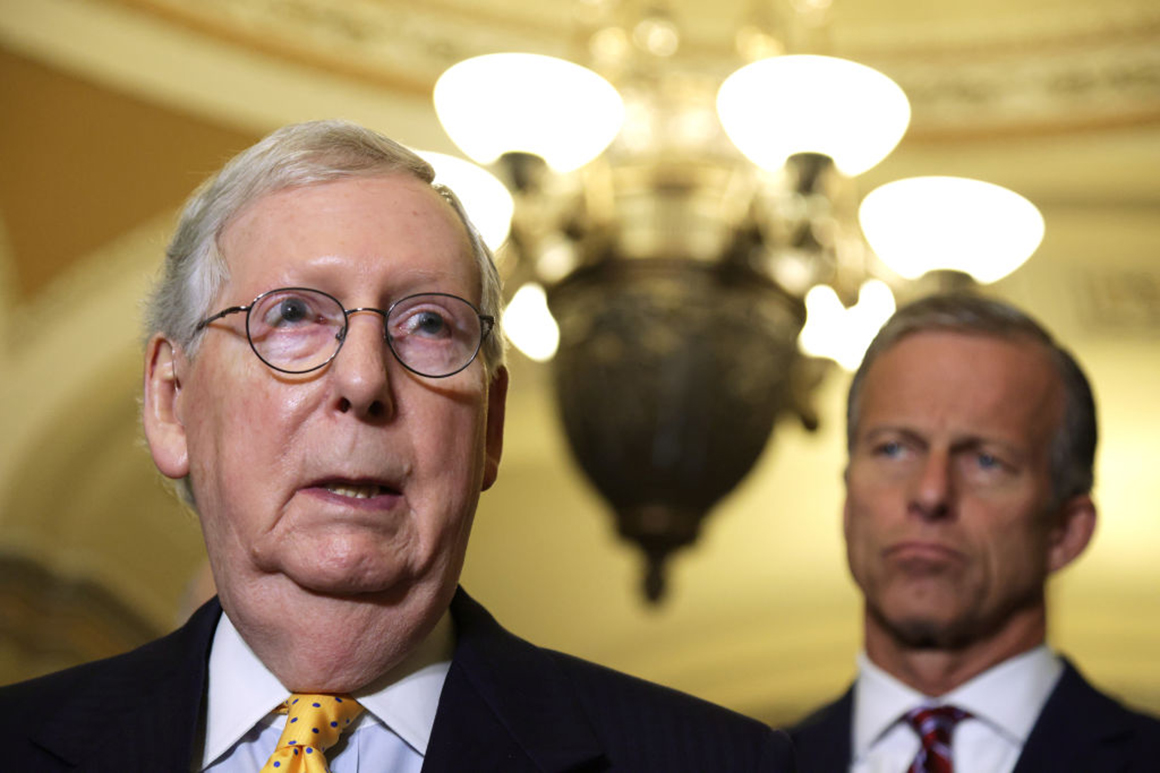

The rumbling on the floor “was the first I heard about it. And then boom, the tweet came out right after that,” said Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), McConnell’s top deputy as the GOP whip. “The leader just kind of let everybody do their own thing, and they did. And he did his own thing.”

That McConnell took such care before revealing his stance reflects deep divisions in his conference over whether to hand Biden a victory on a bill with shaky financing that wasn’t even drafted as it came to the Senate floor. McConnell had opposed the bill on procedural grounds just a week ago, lamenting that moving forward on unwritten legislation did not make sense.

But this week, McConnell did just that, twice advancing the bipartisan infrastructure plan although it split his conference — something he is loath to do. Shortly before the vote and after McConnell announced his position on Wednesday, Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii), a frequent detractor, put his arm on the GOP leader and offered a few warm words after previously predicting he would oppose the bill.

Schatz declined to comment on his conversation with McConnell but conceded that he was “surprised” by the support thus far from the chamber’s self-declared "Grim Reaper" of Democratic legislation.

“I’m happy to admit that I was wrong” if McConnell keeps up support for the bill, Schatz said.

“He said he wanted us to be successful and he was able to be there at the end. I think he realizes it’s important for the institution,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), one of the bill’s chief negotiators. “He probably looked at it and said: ‘Yeah, this is kind of the way we used to do things.’”

McConnell also surmises that if he and his party became the face of obstruction, it could lead Democratic moderates like Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona to waver on the filibuster, advisers said. So in order to keep his veto power intact, McConnell is taking a more conciliatory approach on infrastructure, which he views as less ideological compared to the other issues.

Still, McConnell’s brand is lockstep GOP opposition in the face of Democratic government. And he faces anything but unity in the days ahead. Just 18 of 50 Senate Republicans supported moving forward on the infrastructure accord, with every presumed 2024 presidential contender voting no. Only two members of McConnell’s primary six-person leadership team voted positively on the bill.

Complicating matters for Republicans, former President Donald Trump vehemently opposes the bipartisan proposal. He even threatened to oust Republicans who supported it about ten minutes after McConnell announced his own position.

Thune opposed moving forward on the bipartisan framework, as did Republican Conference Chair John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), Republican Conference Vice Chair Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) and campaign arm chair Rick Scott (R-Fla.), who assailed it as “insane deficit spending.” Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), a former whip who may succeed McConnell, also voted against moving forward, even giving a speech criticizing the effort as “not ready” for the Senate floor.

Yet McConnell praised the effort as a “focused compromise,” even going so far this week as to say he was “happy” to advance it. At the same time, he went out of his way to throttle the bipartisan bill’s companion legislation, a Democratic-only spending plan that raises taxes on the wealthy and spends as much as $3.5 trillion.

Questions still remain about whether McConnell will support the final product, although there’s a growing feeling that in the end, the longtime GOP leader will stick alongside bipartisan negotiators, and his friend, Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), who helped write the bill.

“I’ve always thought he was for this bill. I think he’s been for the bill since Day One,” said Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.), who has opposed moving forward.

McConnell is not whipping his members to support the bill, and there are no plans to develop a conference-wide recommendation to support it, according to a Republican senator. In the end, that means McConnell could be on something of an island in a GOP conference that’s offered unanimous support for him as leader in party elections.

Still, it is entirely possible that the number of Republican votes will grow as the Senate continues its work. Thune and Cornyn said they’re undecided on the final product, though Barrasso said “it’s going to be difficult” to back it.

Ernst said she could vote for the bill if she had the legislative text, time to assess it and if it helps her state’s biofuels industry. Her state’s senior Republican senator, Chuck Grassley, has supported the legislation.

“I know that this is a very popular bill. I think [McConnell’s] glad we’re working on a bipartisan bill, where we have input,” Ernst said in an interview on Friday. “He has not asked me to support. I think he feels very strongly we should each evaluate that bill on our own.”

Among McConnell’s senior leadership team, only Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.), the retiring Policy Committee chair, has supported moving forward on the bill. And his vote didn’t come from any conversation with McConnell.

“When I said I was going to vote yes, I didn’t know McConnell was going to vote yes,” Blunt said, adding that McConnell’s vote was not “shared widely with the conference.”

Despite McConnell’s singular focus on taking back the majority next year, for the most part he’s allowed his members to come to their own conclusions in an evenly split Senate where every member is an important power center. Earlier this year, he told members that their decision in Trump’s impeachment trial was a “vote of conscience.” But McConnell also actively whipped his conference against nominees and vigorously opposed a proposed independent Jan. 6 commission.

McConnell’s position on infrastructure, at least so far, is even more favorable than his approach to the 2013 immigration bill, which he opposed but did not actively try to block. He’s also surprised his colleagues at times, voting for Democratic nominees like Merrick Garland and Loretta Lynch and famously reversing his blockade on a criminal justice reform bill in 2018.

This year, with full control of Washington for the first time in a decade, Democrats made clear they will pursue their agenda with or without GOP support. McConnell and the dozen-plus Senate Republicans who’ve joined him on infrastructure votes are making the calculation that it’s better to put the Republican stamp on something than to get rolled on everything.

“There were only two choices here. One option is: We do a bipartisan bill. And the other option is: The Democrats do a bill on their own. There’s not an option of ‘don’t do anything,’” said Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah), another negotiator of the bipartisan deal. “Leader McConnell recognized this was a better option than just letting the Democrats do this on their own.”