A Kansas City man who spent 43 years in jail for three murders has been released from prison after a judge ruled he was wrongfully convicted.

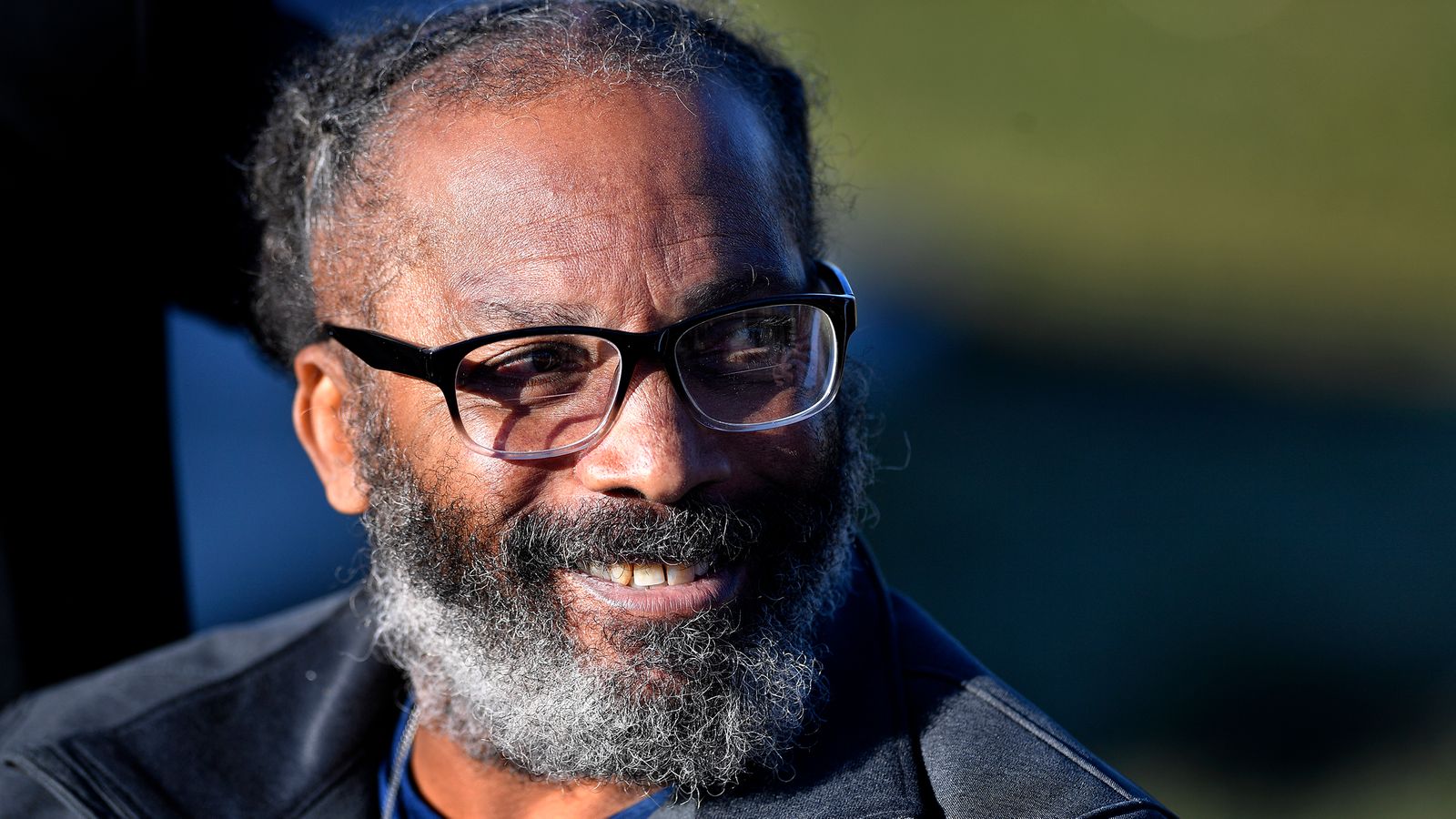

Kevin Strickland, now 62, has always maintained he was home watching television when Larry Ingram, 21, John Walker, 20, and Sherrie Black, 22, were killed.

However, he was convicted on testimony from a witness who identified Strickland as one of four men who shot the victims.

The witness recanted her statement before her death and said after the trial she was pressured by police to identify him as one of the perpetrators.

There was no physical evidence that tied Strickland to the scene of the crime and the two other men convicted in the killings also insisted he wasn’t involved – instead naming two other suspects who were never charged.

Strickland said he found out about the decision when the news scrolled across the TV as he was watching a soap opera.

“I’m not necessarily angry. It’s a lot. I think I’ve created emotions that you all don’t know about just yet,” he said as he left the Western Missouri Correctional Center in Cameron.

Backstage with… Jason Sudeikis: ‘Seeing the world through Ted Lasso’s eyes made it a better place’

Kansas City: Gunman kills one and injures 15 outside bar

Kansas shooting: Police seek two gunmen after four people killed in bar attack

“Joy, sorrow, fear. I am trying to figure out how to put them together.”

In 1979, he faced two trials – the first ended in a hung jury when the only black juror, a woman, held out for acquittal. He was eventually found guilty on three counts of murder by an all-white jury.

His exoneration came about after Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker reviewed the case and believed him to be innocent. However, the Missouri Supreme Court declined to hear the petition.

In August, Peters Baker used a new state law to seek a hearing in Jackson County where Strickland was convicted.

The law – used for the first and only time so far – allows local prosecutors to challenge convictions if they believe the defendant did not commit the crime.

Despite spending almost half a century in jail, the state of Kansas only allows wrongful imprisonment payments to people exonerated through DNA, so he does not qualify for any form of compensation.

“Even when the prosecutor is on your side, it took months and months for Mr. Strickland to come home and he still had to come home to a system that will not provide him any compensation for the 43 years he lost,” said Tricia Rojo Bushnell, executive director of the Midwest Innocence Project, who stood by Strickland’s side as he was released.

“That is not justice,” she said. “I think we are hopeful that folks are paying so much attention and really asking the question of ‘What should our system of justice look like?'”