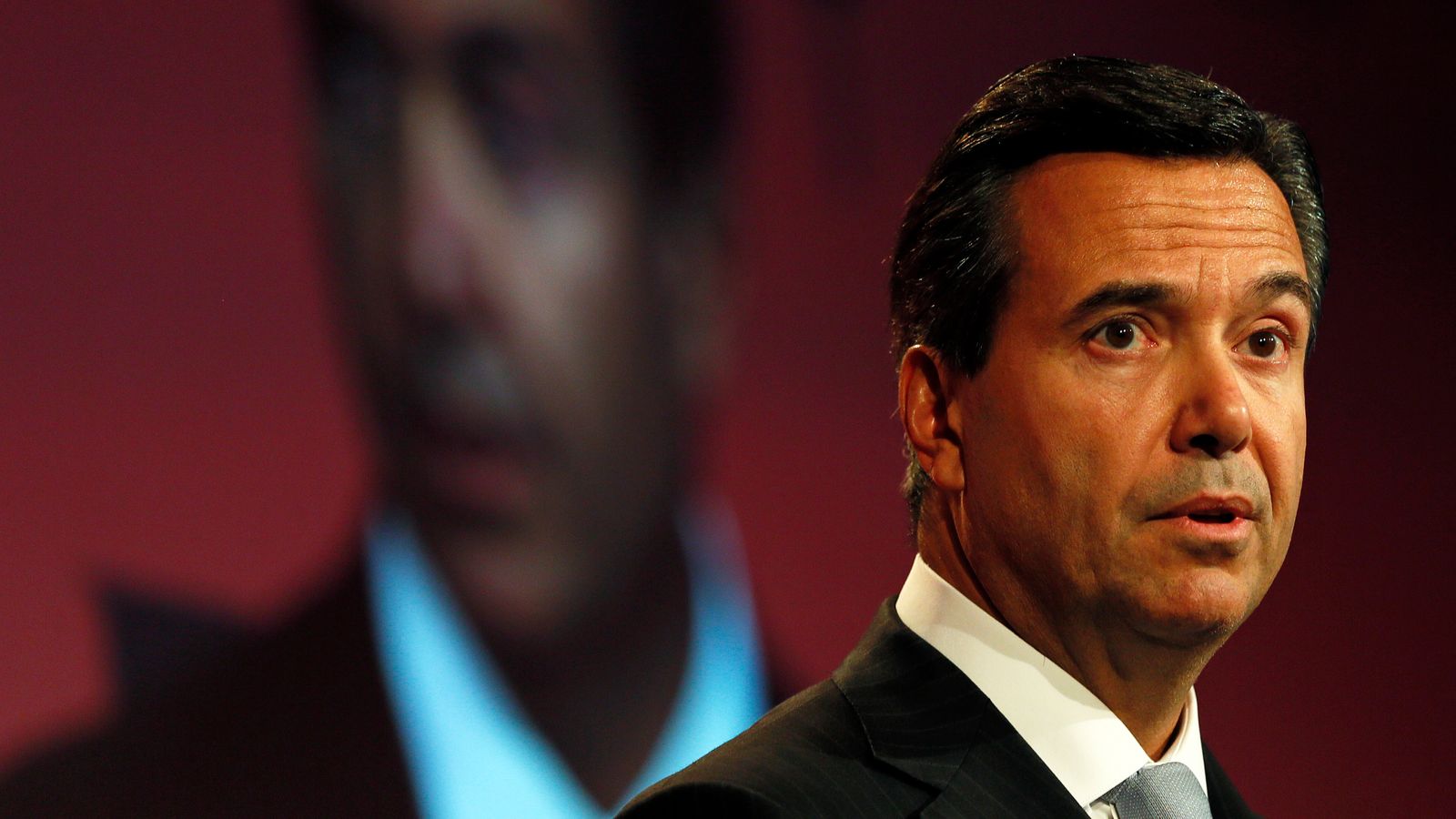

Spare a thought for Antonio Horta-Osorio.

The charismatic Portuguese banker steps down as chief executive of Lloyds Banking Group this month following a distinguished 10-year tenure during which he has stabilised the bank and overseen its return to the private sector following its government bailout in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

One indicator of just how settled things have been at Lloyds during the last decade is that, during Mr Horta-Osorio’s period at the bank’s headquarters on Gresham Street, both HSBC and NatWest Group (the rebadged Royal Bank of Scotland) have each got through three chief executives while Barclays is on its fourth.

Running a big and complex beast like Lloyds – which touches the lives of millions of Britons daily – is hard work and Mr Horta-Osorio, who had previously been chief executive of Santander UK, might have hoped for a quieter time in his next job.

Instead, he has taken on an appointment which might have seemed like a good idea at the time, but which instead now looks like one of the toughest jobs in world banking – the chairmanship of Credit Suisse.

It is not over-egging things to say that Switzerland’s second-largest lender is in crisis.

On Tuesday, it announced it stands to lose $4.7bn (£3.4bn) from the blow-up last month at Archegos, the US hedge fund. That will more than wipe out any profits that the bank would have made during the first three months of the year.

As a result, Credit Suisse is parting company with Lara Warner, its chief risk and compliance officer and Brian Chin, head of its investment banking division. Also going with immediate effect is Paul Galietto, the bank’s head of equities sales and trading, along with a clutch of other executives that include Ryan Atkinson, head of credit risk at the investment bank, and Manish Mehta, head of counterparty hedge fund risk.

This particular crisis comes hot on the heels of the failure of Greensill Capital, the speciality finance firm, with which Credit Suisse had close ties. The bank’s asset management arm oversaw some $10bn (£7.2bn) worth of funds linked to Greensill that were marketed to clients as being low risk but offering a better rate of return than cash deposits.

The funds consisted of packages of IOUs to Greensill from its customers. Those included IOUs issued by the entrepreneur Sanjeev Gupta’s metals empire GFG Alliance which is now said to owe billions of pounds to Greensill. Credit Suisse has to date put the cost of making good client losses at around $3bn (£2.1bn), with an update promised later this week, amid speculation that clients may now also have to take some losses.

In the here and now, though, most pain will be felt by both shareholders and employees. Credit Suisse said today it is cutting its dividend to investors by two-thirds while there will be no staff bonuses this year. Urs Rohner, who Mr Horta-Osorio will succeed as chairman, has waived the CHF1.5 million (£1.15m) bonus to which he was entitled.

The departures of Ms Turner and Mr Chin are an embarrassment for the bank’s newish chief executive, Thomas Gottstein, who promoted them both.

Mr Gottstein became chief executive in February last year when his predecessor Tidjane Thiam, the former chief executive of Prudential, stepped down in the wake of a sensational spying scandal that rocked the bank and the Zurich financial establishment. Some investors had wanted the highly-respected Mr Thiam to remain in place.

The promotion by Mr Gottstein of Ms Warner, who has both Australian and American citizenship, was seen as especially controversial because it brought together two roles – chief risk officer and chief compliance officer. In many other large banks, such as HSBC, Citigroup and Credit Suisse’s local rival UBS, the two posts are kept separate to avoid conflicts of interest.

She is now at the centre of the questions being asked about the bank’s ability to monitor risk.

The Financial Times reported last week that Ms Warner played a crucial role in approving a $160m bridging loan to Greensill in October last year, in spite of objections from risk managers, who were over-ruled.

Stefan Barmettler, editor-in-chief of Switzerland’s oldest business newspaper Handelzeitung, called that decision “unforgivable” in his latest column.

He wrote: “She knew exactly where a bank’s best hunters are gathered: in investment banking.

“This admiration for hunting fever in the wildest of all banking disciplines is astonishing. There was also the chairman, Urs Rohner, who for a decade has been instructing his executives to keep a tight rein on the investment bankers and to exorcise gambling fever from the proud Swiss asset management bank once and for all.”

Mr Barmettler wrote that, of 14 employees in the bank’s anti-money laundering department, 11 had quit amid unhappiness at her management techniques.

He went on: “Warner’s compliance team was never told that its work was essential for the bank’s reputation; rather, it was dismissed as a brake and cost factor.”

There are now big questions about where the bank goes from here. Certainly its ability to take on risk in the future – the prime skill-set in banking – and its ability to monitor those risks will be under scrutiny. The failure to unwind exposure to Archegos as rapidly as Wall Street banking giants, such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, will also have wounded Swiss pride.

There are already calls for radical surgery, for the investment banking division, long seen as a drag on the bank’s overall performance, to be hived off or pared back, while speculation from a couple of years ago that Morgan Stanley could make a takeover approach have started to do the rounds again.

That might not get past the Swiss government or other regulators.

But one thing is abundantly clear: Mr Horta-Osorio has his work cut out.