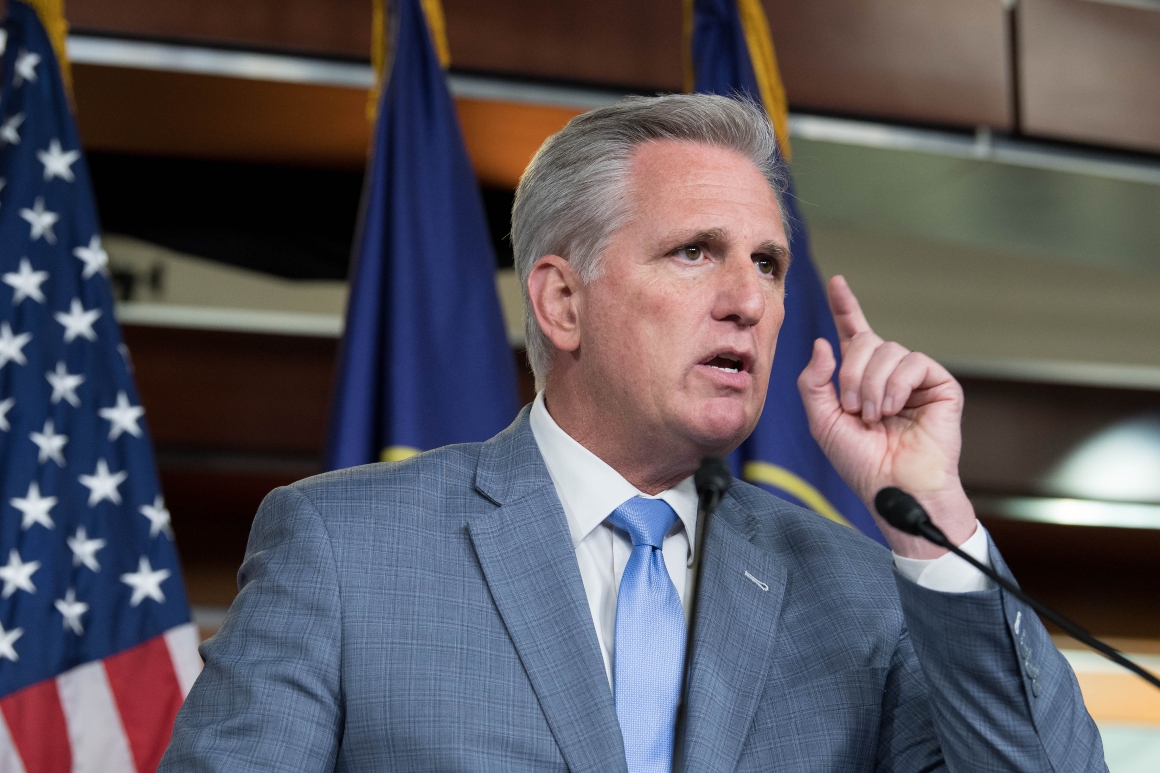

The Jan. 6 select committee has subpoenaed five Republican congressmen, including Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and Rep. Jim Jordan.

The subpoenas target some of former President Donald Trump’s closest allies in the House, several of whom were engaged in numerous meetings and planning sessions amid Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election results. The move represents a sharp escalation in the select committee’s tactics after months of weighing how aggressively to pursue testimony from their own colleagues.

In addition to McCarthy and Jordan, the panel sent summons to Reps. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) and Mo Brooks (R-Ala.). All five lawmakers have rejected investigators’ previous requests that they voluntarily testify.

The subpoena demands testimony from the five lawmakers in the final week of May. Spokespeople for the members did not immediately return a request for comment.

Members of the select panel have wrestled for months with the question of how to handle their GOP colleagues. Chair Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) had previously expressed skepticism that subpoenaing lawmakers would be advisable, as it would likely trigger a lengthy legal fight unlikely to be resolved before in the current Congress. But the panel’s thinking appears to have changed, as every avenue of the probe led investigators toward fellow House members.

Some of the subpoena targets — and several other GOP lawmakers — were regularly in contact with Trump and the White House in the weeks leading up to Jan. 6. They helped amplify false claims about the integrity of the 2020 election and were among the earliest to call on colleagues to challenge the results.

But members were mindful that demanding testimony from lawmakers would potentially set a precedent. While House and Senate ethics committees have subpoenaed members and staff before, there’s little precedent for an investigative committee — particularly one mainly guided by the majority party — turning its subpoena powers on fellow members of the House.

The lawmakers receiving subpoenas are expected to cite the protections of the Constitution’s “speech or debate” clause, which prohibits lawmakers from being sued for their official government business. That could trigger a complex and prolonged legal battle, and it’s unclear whether the select committee would pursue expedited consideration from the courts, which could still take months. The committee is preparing to hold a series of public hearings to lay out its findings next month, and the panel will almost certainly be disbanded next year if Republicans take the House majority.

The panel is particularly interested in McCarthy’s account of a phone call with Trump as rioters descended on the Capitol on Jan. 6. McCarthy, according to accounts provided by another GOP lawmaker, grew heated as Trump attempted to pin blame for the violence on antifa. When McCarthy said the riot was made up of Trump supporters, Trump purportedly replied, “Well, Kevin, I guess these people are more upset about the election than you are.”

The subpoena also comes after leaked audio, obtained by The New York Times, showed McCarthy was sharply critical of Trump in the days immediately following the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, even suggesting to colleagues he wanted Trump to resign. But McCarthy abruptly changed course in the following weeks, meeting with Trump in Mar-a-Lago and embracing Trump’s continued hold over the GOP.

Jordan, a close Trump ally, had drawn the attention of investigators over his calls and communications with Trump on and before Jan. 6. Cassidy Hutchinson, a close aide to then-White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, told the select committee that Jordan was regularly in contact with the White House amid strategizing efforts centered on keeping Trump in office. He was present in meetings, Hutchinson said, when the White House counsel pushed back on certain proposed tactics.

Perry, who is now the chair of the pro-Trump House Freedom Caucus, had played a role in attempting to install Trump ally Jeffrey Clark as the acting Attorney General. Investigators obtained texts between Meadows and Perry about Clark, who declined to provide substantive testimony to the panel. Clark had pushed for DOJ to cast a cloud over the election results and encourage state legislatures to reconvene and throw out election results that supported Biden — an important element of Trump’s last-ditch attempt to prevent the transfer of power.

Trump recently turned on Brooks, who was one of his earliest and closest allies in the effort to prevent Joe Biden from taking office. Trump dropped his endorsement of Brooks in Alabama’s contested Senate GOP primary after Brooks began flagging in polls. Shortly after their falling out, Brooks alleged that Trump had pressured him — in recent months — to attempt to “rescind” the 2020 election and reinstate Trump as president.

And Biggs has faced scrutiny from the select committee for alleged contacts with organizers of Jan. 6 rallies that preceded the attack on the Capitol. Plus, the panel has said there’s evidence he was involved in discussions about pardons for people connected to Trump’s effort to subvert the election.