A small crowd has gathered, shuffling to keep warm and talking quietly. All of them are men, some in traditional Afghan clothing, others in jeans and jumpers; all of them pensive.

At the heart of the crowd is Safi, and in his hand is a passport. It belonged to his uncle, Muhammad, one of the victims of the boat tragedy in the Channel last month, in which at least 27 people died.

Muhammad’s body was recovered from the water and brought here, to the morgue in Lille. And that’s why people are gathering now.

In just a few minutes, his uncle’s body will be taken from here, along with those of three other victims, and driven to a mosque in the French city.

There will be tears and memories, and then the body will begin its journey back to Afghanistan. But before all that, Safi is waiting, and talking.

“The UK helped the people of Afghanistan by evacuating them but at least they were alive,” he says. “But here in the water there were Afghans who were dying and they didn’t help them.

“I’m so sad today. It’s such a sad day. It’s so important that the bodies are transferred back to Afghanistan because some of their families still don’t know that they’ve died.

What is the Nationality and Borders Bill, why is it so controversial and what do MPs want to change?

Migrant crossings: France rejects Boris Johnson’s call for joint British-French patrols in the Channel

Channel crossings: Victims ‘held hands in order not to drown’ after boat capsized on way to Britain

“There’s just one family member there who knows and we are in contact with them. It’s important that they return and are buried there.”

But if the deaths of these people could have acted as a warning, then it has not been heeded.

Boats are still setting off from the shores of northern France, overloaded with desperate people, and the squalid camps around Calais are still full.

There used to be a lull in winter, when the number of people trying to cross the Channel would fall to almost zero. But now that has changed.

Thanks to more sophisticated policing, it’s become ever harder for a person to smuggle across the Channel hidden in a vehicle, so the water route has become the dominant choice at any time of the year.

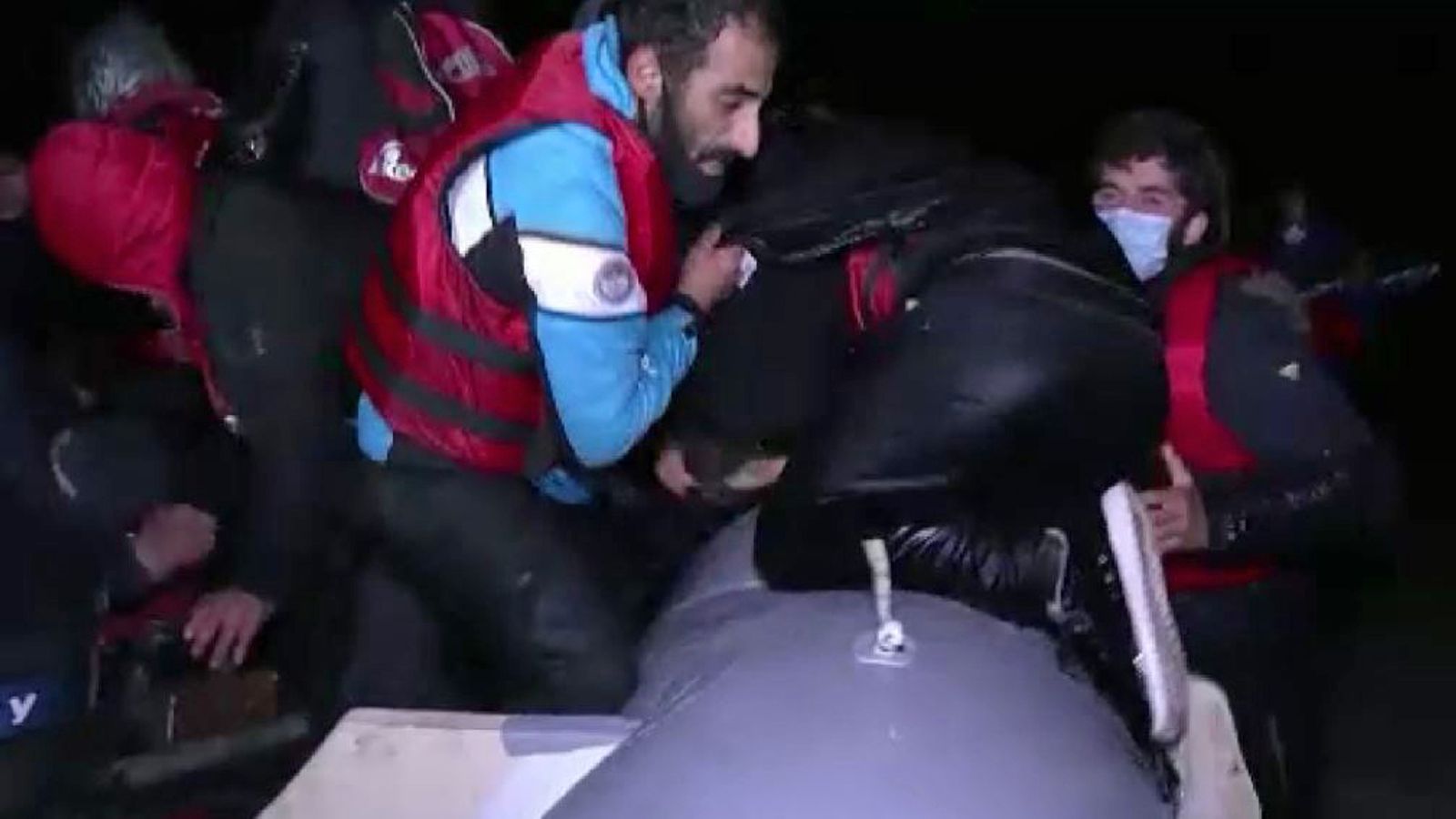

And so it is that the French police have been intercepting boats late at night and early in the morning.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

When we visited camps around Calais, we spoke to a succession of people who all said they were planning to try to cross the Channel, and seemed largely indifferent to the danger.

“If I die, then I die,” one man said to me, smiling at the roadside. “I want to get to England. Everyone says that England is very good.”

Some of these boats are apprehended by French police, who have certainly increased their presence around the beaches. But plenty still get into the water, where they are hard to spot.

Now, though, there is another layer of surveillance.

Immediately after the drownings in the Channel, Frontex, the European border agency, agreed to send a plane to monitor areas in France, Belgium and Germany.

The plane is supplied by the Danish Air Force, and fitted with a series of cameras that can see comfortably across long distances in the dark, as well as sophisticated radar systems.

We saw it fly over us while filming on a beach at night. The following morning, we were at Lille airport to meet the crew as they landed. Among them was Tim, one of the pilots.

“It’s not at all boring,” he told me. “Today, five and a half hours went super fast. It was the most interesting flight we have had so far – a lot of things happened.

“From the moment we got to the plane this morning, we were told there were already boats in the water and from when we got out there, we started picking out boats that we could relay to the maritime rescue coordination centre.

“We could give them details of how many people, where they are, which way they were going, the conditions of the boats.

“Then we had a lot of people on the shore as well, getting ready to get into boats and we could coordinate with the local police to get to them before they could get into the water, and destroy the boats.”

It is exactly the sort of coordinated response that is designed to both stem the flow of people crossing the migrants, and also to staunch the anger of British politicians, foremost among them Priti Patel, who have complained regularly that too little has been done to stop migrants leaving the French shores and starting the journey towards the UK.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Now, with a plane flying overhead and more police on patrol, Europe (and, let’s be honest, this is mainly about France) will hope to change the shape of the argument, as well as preventing another tragedy.

And yet the reality is that this isn’t a political story, really.

Around Calais, you can see the clusters of temporary camps that have sprung up. They are miserable, squalid places populated by scared and desperate people, who are here for just one reason – a burning desire to reach British soil.

However cold it gets, that reality won’t change.