Republicans are feeling so good about their chances of retaking Congress this fall that they’re already debating their governing relationship with President Joe Biden. And they’re divided over how to handle their potential big wins.

With Biden and Democrats floundering right now, the GOP is increasingly favored to vault back to partial power in Washington by flipping the House, and potentially also the Senate, in the coming midterms. What comes next isn’t quite clear: Some Republicans are mulling ways to collaborate with Biden on issues like trade, energy or tech; others are prepared to go scorched-earth as their party eyes the bigger prize of retaking the White House in 2024.

The GOP’s pro-bipartisanship camp may not have a lot of space in 2023 to work with the president: funding the government and raising the debt ceiling will be a major challenge, given how often House and Senate Republicans diverge on critical pieces of legislation. And former President Donald Trump will continue trying to influence the party’s direction, criticizing Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell and anyone else who steps out of line with his combative politics.

Given those dynamics, there’s no unified GOP agenda for voters to examine this fall — other than an up-or-down vote on Biden and congressional Democrats’ record. Republicans aren’t sure what will happen next if they actually win.

“It’s really going to be a referendum on him and his administration and on the Democrat leadership in the Congress,” John Thune, the No. 2 Senate Republican who is also running for reelection this fall, said of Biden. "So we need to stay out of our own way."

“It’s really important for us to highlight our differences, how we would do it differently," the South Dakotan added. "And then … have some things that we would do or could do if there was a willingness to work together.”

For now it’s Democrats, holding shaky but singular power in Washington, consuming the Capitol’s oxygen as they struggle to enact Biden’s agenda. But the GOP’s splits over whether to work with Biden, even now from the minority, would become the nation’s central political story if it retakes part or all of Congress this fall. With that victory would come the messy job of actually governing, preventing credit defaults and government shutdowns at a minimum.

And just as a trio of conservative senators once battled former President Barack Obama on all fronts as they sought the White House, there’s a stable of Senate and House Republicans with national political ambitions that could cut against any attempts to collaborate with Biden. Not to mention the passel of Republicans disinterested in the presidency who are already signaling they’ll push to block Biden at every turn.

“Putting a stop to his agenda is the first thing that we would do, because that’s presumably what people would be voting for,” said Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.), a potential 2024 GOP White House hopeful who led the objections to Biden’s election certification. “The message would be: If we’re in the majority, we need to stop what he’s currently doing.”

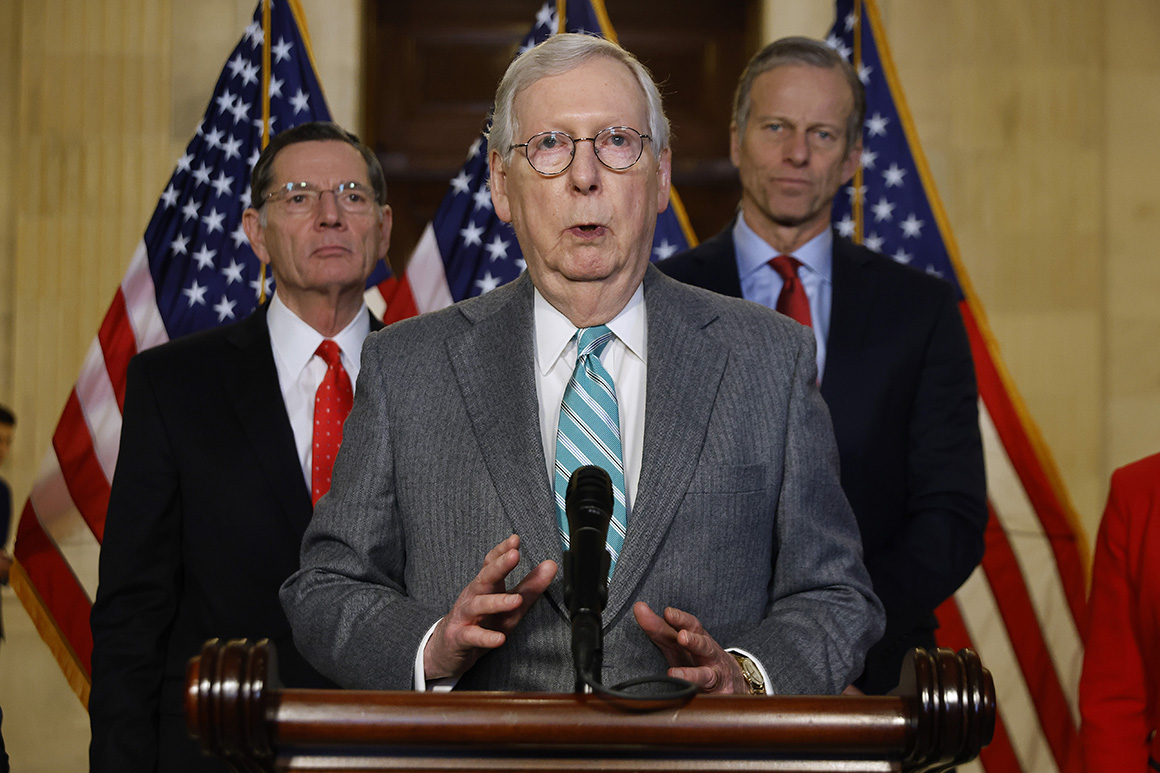

Still, the most powerful Senate Republican has indicated an openness to work with Biden. Already feeling bullish on his party’s chances this fall, McConnell said in a late-September interview: “I don’t think people send us here to do nothing.”

“When you have a closely divided government, or a divided government," McConnell added then in previously unreported comments, "I think the American people are saying, ‘We know you have some big differences, and either of you may not be able to move the ball the way you’d like to. But why don’t you look for things you agree on, and do those?’”

McConnell pointed to trade as a potential area of future cooperation with Biden.

As Senate majority leader during the last two years of Obama’s administration, McConnell famously blocked the president from filling a Supreme Court vacancy and slowed other judicial confirmations to a trickle. McConnell won’t say how he’d handle a Supreme Court vacancy if one comes up in 2023 or 2024 and he controls the Senate, though Democrats are positive he wouldn’t fill one for Biden either.

Yet McConnell also cut a deal with Obama to fast-track new trade deals that then-Democratic leader Harry Reid did not lend a hand with. McConnell later clinched a bipartisan transportation deal with Obama and Democrats. As minority leader during this Congress, McConnell signed off on a huge Biden-backed infrastructure bill and after repeated threats that he would do otherwise, allowed the debt ceiling to increase.

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and House Republicans opposed those accommodations by the Kentucky Republican — as did Trump. And unlike McConnell, McCarthy and his conference are in the thrall of the party’s former president. That means the House Freedom Caucus and other allies of the former president will be trying to maximize Democrats’ losses even at the expense of legislation some rank-and-file Republicans would otherwise support, particularly in the Senate.

When asked about areas House Republicans could team up on with the Biden administration, Georgia Rep. Drew Ferguson, a member of GOP leadership, replied tersely: ”On anything that’s not socialist.”

That public posturing reflects a real concern among some Republicans that Biden might not be willing to pivot from his current agenda of expanding social and climate programs, and gutting the filibuster to pass elections reform, in order to work with Republicans on what would probably be small-bore issues. With a bipartisan infrastructure package already law, there’s fewer obvious opportunities for collaboration with the other party at the moment.

Rep. John Curtis (R-Utah) suggested immigration as an avenue for partnership. House Minority Whip Steve Scalise (R-La.) wants to work with Biden on battling inflation. Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) said Republicans could talk to Biden about making Social Security “more sustainable.”

But it’s hard to imagine a split government delivering on even one of those big-ticket items. And some Republicans are already downplaying any ideological intersection with Biden after the past year.

“Are we going to get the president that was a self proclaimed dealmaker in the Senate for his entire career? Are we going to get the guy that’s down in Georgia [for] a face-saving speech to his base because he can’t get something through the Senate?” asked Rep. Kelly Armstrong (R-N.D.). “A lot of it depends on which president we get.”

Indeed, Armstrong and other Republicans singled out the tone of Biden’s speech in Georgia last week, in which the president suggested that lawmakers who oppose Democrats’ voting rights legislation will be on the same side of history as segregationists and the head of the Confederacy. McConnell quickly condemned Biden’s remarks, calling them “beneath his office," and Biden later sought to clarify that he hadn’t made that direct comparison about the GOP leader.

One telling metric: Even Republicans who voted to impeach Trump last year aren’t sure whether they can find any substantive common ground with Biden if they are in the majority.

“Boy, my answer would have been a lot different a year ago,” said freshman Rep. Peter Meijer (R-Mich.), who voted to impeach Donald Trump earlier this year. “I’ve been astounded at the number of areas where we’ll talk with people from the administration. … And then just nothing happens.”