Donald Trump just can’t seem to quit 2020. That means Republicans can’t either.

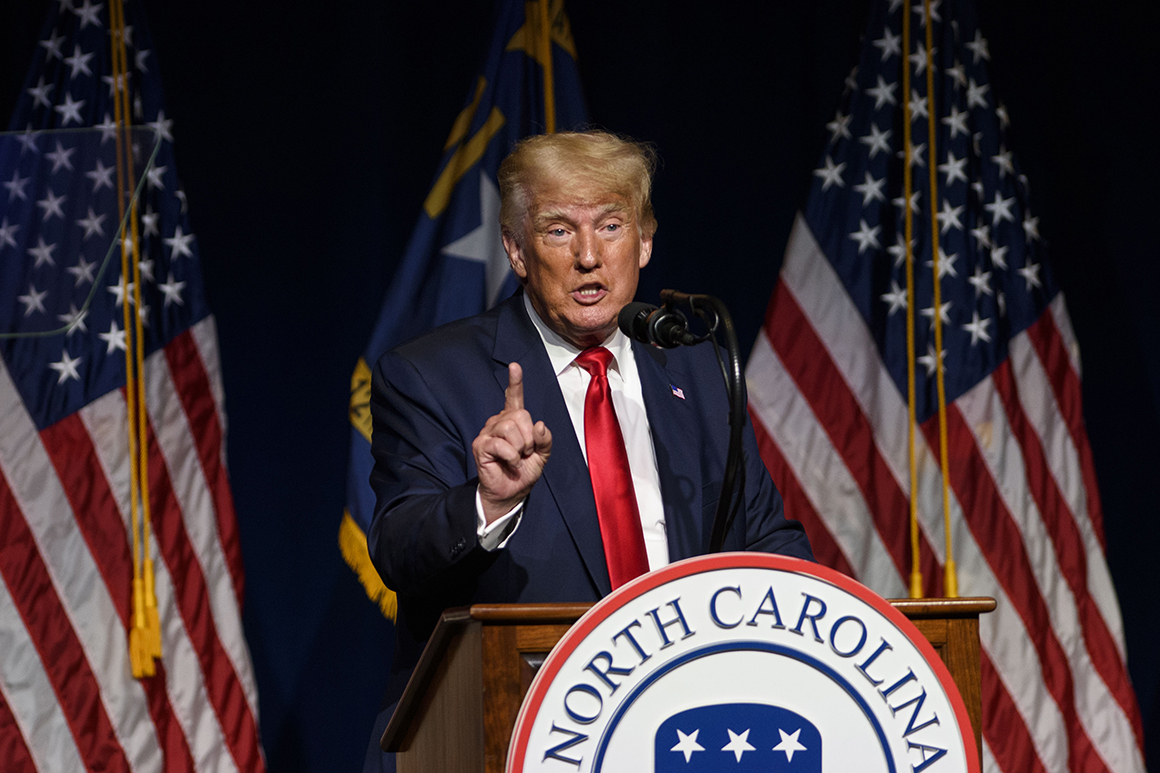

The former president is returning to the national spotlight with plans to play a central role in the GOP’s push to reclaim power, huddling with members of the conservative Republican Study Committee at his New Jersey resort last week. Trump told the crew there he is “more motivated than ever” to be engaged in House and Senate races, according to RSC Chair Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.).

But he brings with him the baggage of his repeated false claims that widespread voter fraud cost him the White House. In recent public settings, Trump has called his loss to President Joe Biden "the crime of the century" and likened it to a stolen "diamond" that needs to be returned. He’s gone even further in private, reportedly entertaining the wild conspiracy theory that he could be reinstated as president in August. Some Republicans are palpably relieved that he hasn’t said that publicly — at least not yet.

The spectacle caused by Trump’s revival of unfounded voter fraud claims offers an early preview of the type of headaches facing Republicans who want to put him center stage in their quest to win back their congressional majorities, particularly the House GOP. Yet some members worry that Trump’s election grievances could create an impossible-to-avoid litmus test in 2022.

GOP candidates are bound to field questions about whether they agree Trump was cheated in the election — an uncomfortable position for some lawmakers who don’t want to cross an ex-president who still maintains an iron grip on the party. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) insisted last month that “no one is questioning the legitimacy of the presidential election,” but the more he aligns with the legitimacy-doubting Trump, the more likely those words are to come back to bite him.

”If Trump focused on Pelosi and Biden’s policy failures, he would help us. If it’s about election fraud and sour grapes from 2020, it will hurt us,” said one GOP lawmaker who represents a purple district. “We may be able to still win the majority, but I think it makes the hill harder to climb.”

“Obviously, the base likes it, but the base doesn’t win the majority in the House,” the lawmaker added.

Banks, for one, said Trump was focused during their meeting last week on how he could "stump around the country for candidates to help us win back the House." The ex-president did not give any signals about whether he plans to run again in 2024, Banks said, nor did he spend much time harping on the 2020 election or bringing up state election audits such as Arizona’s.

“He was all about the future,” Banks said. “It was not focused on the past.”

That’s the kind of Trump that Republicans would much prefer to see this cycle. Retiring Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) used a recent appearance on NBC’s “Meet the Press” to urge Trump to move on from baseless electoral grievances: "He could be incredibly helpful in 2022 if he gets focused on 2022 and the differences in the two political parties,” Blunt said.

But it’s not clear whether the freewheeling former president can stay focused on 2022 as he hits the trail for Republican candidates, and that uncertainty is far more than a mere potential political problem for the GOP. Some Republicans fear Trump’s 2020 election rhetoric, which incited a deadly mob to attack the Capitol and ultimately led to his second impeachment, threatens to undermine democracy and risks inspiring more violence.

“The continuing false claims of a stolen election have led to violent/death threats, intimidation, and claims of prison time coming for elections workers. They keep coming,” Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, who refused to overturn his state’s election results, tweeted Friday. “Real leaders need to take steps to stop it. So far they haven’t.”

Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.), who was stripped of leadership power last month for her repeated rebukes of Trump, has continued to issue similar dire warnings.

“The problem we’ve got now is he’s continued to say the same things. He’s continued to use the same language that provoked that violence on January 6th,” she said during a recent Wyoming radio interview. “When you look at what’s necessary for us as a country, when you look at what’s necessary for us to sustain our republic and to sustain our democratic process, the things that he is saying are very toxic and dangerous, and as Republicans we have to stand up against those lies.”

McCarthy, who initially condemned Trump’s role in the Capitol riots but has since bear-hugged the ex-president, is feeling confident about winning back the House majority. And he sees the former president as crucial for GOP turnout and fundraising, trekking down to Trump’s resort in Florida to stay in his good graces. Posing for a picture with Trump while flashing a thumbs-up at one of his properties has almost become a rite of passage among the highest-ranking Republicans.

But even McCarthy seems eager to put 2020 in the rear-view mirror. The GOP leader argued last month that booting Cheney from the leadership team was necessary so that House Republicans could start healing from their Jan. 6-related wounds and finally focus on hammering the Biden agenda, which the GOP believes is a winning midterm message.

Republicans are also eager to exploit tensions across the aisle as the House returns to Washington this week. During a conference call on Friday, House Republicans reveled in growing Democratic divisions over everything from infrastructure to Rep. Ilhan Omar’s (D-Minn.) latest remarks on foreign policy, according to a source on the call.

Yet McCarthy and the GOP may find it difficult to avoid litigating Trump’s election loss if the former president is out there doing it himself while stumping for their candidates.

McCarthy “is the one that said Trump was the leader of our party,” said Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.), one of the most vocal Trump critics in the GOP. “He’s given his leadership card to the president. So if the former president is looking backwards, you don’t have a choice.”

By contrast, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Senate Republicans have shown more independence from Trump. But McConnell, despite torching Trump for inciting the insurrection, has since been careful not to poke Trump in the eye and assiduously avoids questions about the ex-president.

Republicans on both ends of the Capitol wish Trump would strike a forward-looking tone more often in public settings. Some of them are warning of a Georgia repeat, when Democratic candidates captured a pair of Senate seats — and with it, control of the upper chamber — after Trump repeatedly claimed the state’s election system was rigged instead of trying to drive more GOP voters to the polls.

“He should have learned from what happened in Georgia," the purple-district Republican lawmaker said. "He cost us Georgia by focusing on the election."