When Senate Democrats are in a jam, a question sometimes quietly bubbles up on Capitol Hill: What would Harry Reid have done?

That the query itself still surfaces five years after Reid left the Senate is a mark of respect for the pugnacious longtime Democratic leader and his brute force style of leadership, which the public and politicos alike are remembering anew after Reid’s death Tuesday. These days, longtime senators and staffers wonder how the feisty Nevadan would have handled problems such as Sen. Joe Manchin’s resistance to President Joe Biden’s agenda and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema’s outspoken refusals to significantly change the filibuster rules.

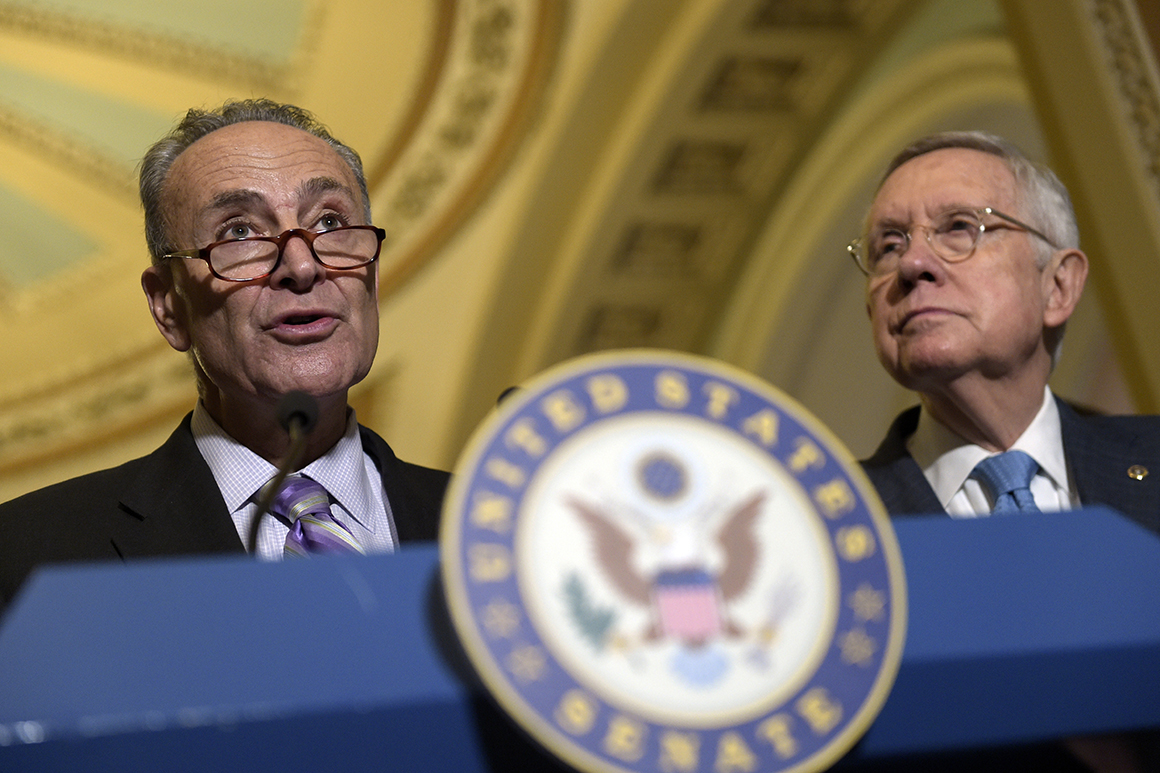

Chuck Schumer, now majority leader, was a close personal friend and protege of Reid’s, and their shared leadership of the Senate Democrats over the past 15 years has defined the caucus from top to bottom. For all their similarities and partnerships, the former boxer from small-town Searchlight, Nev., and the chatty pol from Brooklyn each developed their own view of how to run the fractious Democratic Caucus.

While Schumer leads the party with relentless messaging discipline and a focus on lockstep party unity, Reid favored all-out political combat. Sometimes Reid battled members of his own party, but he reveled in partisan bomb-throwing.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Reid once notably took to the Senate floor together in 2015 to dispute the tone of a POLITICO story on their relationship, which was scraping rock bottom. But remembering Reid on Tuesday, McConnell put it this way: “When Harry retired from the Senate, we both celebrated the fact that our many differences had never really gotten personal.”

“The nature of Harry’s and my jobs brought us into frequent and sometimes intense conflict over politics and policy. But I never doubted that Harry was always doing what he earnestly, deeply felt was right for Nevada and our country," McConnell said.

Yet their battles set the stage for today’s tenuous balance of power in a Schumer-led 50-50 Senate, with many Democrats now openly warning that the supermajority threshold’s days are numbered given the difficulty in assembling 60 votes for their party’s priorities like elections reform. Those dominoes began falling after Reid invoked the so-called nuclear option in 2013, eliminating the filibuster on most nominations. It was one of the most consequential decisions made in the Senate this century — and Schumer had Reid’s back.

Reid felt he had to do it to overcome McConnell’s obstruction of then-President Barack Obama’s nominees. He also believed the Senate’s supermajority requirement was at the useful end of its life span. McConnell repeatedly warned it would harm the institution, and in subsequent years the Kentuckian twice changed the filibuster rules to further ease confirmations for a GOP president.

But Reid had the votes to make the most consequential change, with margins Schumer can only dream of in today’s closely contested Senate. In 2013, Manchin’s opposition, along with two other senators, didn’t matter in a chamber where Reid controlled 55 votes and just needed a simple majority for a rules change.

And with Schumer working on the political side during Reid’s tenure as Democratic leader, the Senate Democrats built up a whopping 60-seat majority in 2009, allowing Democrats to pass much of the generational health care reform without even having to use the clunky and limiting budget reconciliation process. Working closely with Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the Democrats’ massive majorities then eased the otherwise difficult circumstances at the start of Obama’s presidency.

At the moment, Schumer is left with 50 seats — severely handicapping what can be done on both Biden’s agenda and to the fabric of the Senate entirely.

In his fights with Republicans, such as the 2013 shutdown over Obamacare, Reid demonstrated to Schumer that Democrats could not give an inch in major partisan confrontations. It was a lesson Schumer took into this year’s battles with Republicans over the debt limit and McConnell’s initial refusal to organize the 50-50 Senate without concessions. Though Schumer faces the longest 50-50 Senate ever and the grueling pandemic, Reid was confronted with heading off fiscal calamity during the Great Recession and a hardline GOP strategy to stop Obama’s agenda entirely in its tracks.

Remembering Reid, Schumer called him “my leader, my mentor, one of my dearest friends.” The two continued speaking regularly since Reid left office.

Reid’s and Schumer’s politics shifted alongside each other and within an increasingly left-leaning Democratic Party. Once viewed with deep suspicion by liberals, Schumer has largely shed his reputation as a Wall Street-friendly Democrat. During his last term, Reid kicked his longtime conservative bona fides to the curb. Reid’s majority was stacked with moderates from red states; Schumer’s senators from Arizona and Georgia reflect the new direction of the party.

And Reid ended up a champion of filibuster reform, predicting the legislative filibuster was on its way out in recent months. Schumer, too, now openly speaks about rules reform, but to get there he needs to convince Manchin to jump with him — something Reid never accomplished.

The two Democratic leaders handled Manchin in totally different fashions. When Reid left the Senate in 2016, Manchin openly aired frustration with the combative Nevada Democrat, blasting him for criticizing the election of former President Donald Trump. Today, Manchin is far more comfortable with Schumer’s accommodating vibe than Reid’s hard-nosed leadership tactics. Nonetheless, every few days Democrats wonder if more pressure on Manchin might be necessary.

When he decided to retire in 2015 following a painful exercise injury, Reid moved quickly to cement his legacy. He endorsed Schumer as his successor and promptly backed Catherine Cortez Masto to succeed him in Nevada. His political machine ensured she won both the primary and the general election; the battleground state has become one of Democrats’ brightest spots in the past decade.

It’s all part of Reid’s remarkably effective record as party leader, which nonetheless chafed some of his colleagues. Six Senate Democrats voted against him in his last leadership election after Democrats lost the Senate in 2014, a sign of how polarizing he was within the Democratic Party.

Yet even during that period of discontent, Democrats credited Reid with having the party’s best interests in mind as he drew relentless heat from Republicans for not allowing more amendment votes.

“If there were mistakes made, they were mistakes that came from Harry Reid meaning well. And by that, he was trying to protect members from difficult political votes,” said former Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) in an interview after the 2014 election.

Schumer, on the other hand, frequently preaches party unity as a strength and takes close notice of his members, sometimes calling them up when he reads an eyebrow-raising quote in the paper. Reid knew early on that the two close friends approached leadership differently.

“He’ll be a good leader. He won’t be like me, we’re different,” Reid predicted in a 2016 interview. “Two different personalities. He’s a press guy, I’m not.”

Where Schumer is methodical, Reid was spontaneous, firing off fiery quotes in hallway interviews, press conferences and on the Senate floor. He rarely dodged questions. In what was expected to be a humdrum press conference in 2014, he casually explained he wasn’t going to put Obama’s fast-track trade bill up for a vote. He showered Mitt Romney with dubious attacks on the Senate floor in 2012.

And Reid was unrepentant about his tactics a few years later. He explained the entire Romney episode in blunt black and white: “Romney didn’t win, did he?”

His frustrations that Democrats had failed to stop Trump in similar fashion greatly bothered Reid. As he left office, he excoriated Trump as a “sexual predator who lost the popular vote.” But even though he was still the minority leader, Reid also began largely deferring to Schumer in his final weeks in office.

As Reid prepared to retire in December of 2016, Schumer was immediately confronted with a tough fight. Many Democrats wanted to protect coal miner benefits and were even talking about voting against funding the government to make their point. In the end, Schumer helped Senate Democrats get their issue visibility in the press but didn’t force a shutdown fight. Throughout the drama, Reid mostly let his successor handle it.

And for the first time Democrats asked themselves: What would Harry Reid have done?