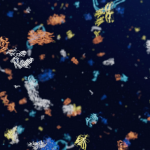

A new image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) shows at least 17 dust rings resembling a fingerprint created by a rare type of star and its companion.

Located more than 5,000 light years from Earth, the cosmic duo is collectively known as Wolf-Rayet 140 (WR 140).

Each ring was created when the two stars came close together and the streams of gas they blow into space collided, compressing the gas and forming dust.

The stars’ orbit brings them together about once every eight years, with the dust loops marking the passage of time.

Ryan Lau, an astronomer at the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab, said: “We’re looking at over a century of dust production from this system.

“The image also illustrates just how sensitive JWST is. Before, we were only able to see two dust rings, using ground-based telescopes. Now we see at least 17 of them.”

Webb’s Mid-INfrared Instrument (MIRI) is uniquely qualified to study the dust rings, which researchers call shells, because it sees in infrared light, a range of wavelengths invisible to the human eye.

NASA’s Dart mission successfully shifts asteroid’s orbit after deliberate crash

Moment NASA spacecraft crashed into asteroid captured by telescopes

Why NASA crashed a spacecraft into a harmless asteroid at 14,000mph

The UK Astronomy Technology Centre (UK ATC) helped design and build MIRI’s spectrometer, which have been used to reveal the composition of the dust, formed mostly from the material ejected by the special type of star known as a Wolf-Rayet star.

Such a star is born with at least 25 times more mass than the Earth’s sun and is nearing the end of its life.

Burning hotter than when it was younger, a Wolf-Rayet star generates powerful winds that push huge amounts of gas into space.

The Wolf-Rayet star in this pair may have shed more than half its original mass via this process, experts suggest.

They say while some other Wolf-Rayet systems form dust, none are known to make rings like Wolf-Rayet 140.

They said the unique ring pattern forms because the star’s orbit in WR 140 is elongated rather than circular.

Only when the stars come close together, around the same distance from the Earth to the sun, and their winds collide, is the gas under sufficient pressure to form dust.

The astronomers think WR 140’s winds also swept the surrounding area clear of residual material, which could explain why the rings are so pristine.

Dr Olivia Jones, Webb Fellow at the UK ATC in Edinburgh, and a co-author of the study, said: “Not only is this a spectacular image but this rare phenomenon reveals new evidence about cosmic dust and how it can survive in the harsh space environments.

“These kinds of discoveries are only now opening up to us through the power of Webb and MIRI.”

The findings are published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Last month the telescope took its first image of a planet outside of the solar system, and has previously revealed stunning details of the Cartwheel Galaxy and observed a dying star and a “cosmic dance”.