A new era has dawned in Washington, but the divide over pandemic relief on Capitol Hill is strong as ever. Even Democrats aren’t sure of their next steps.

With the party’s full takeover of Washington complete, top lawmakers are eager to quickly deliver a new aid package as the virus’ toll worsens by the day. That’s about where the agreement ends.

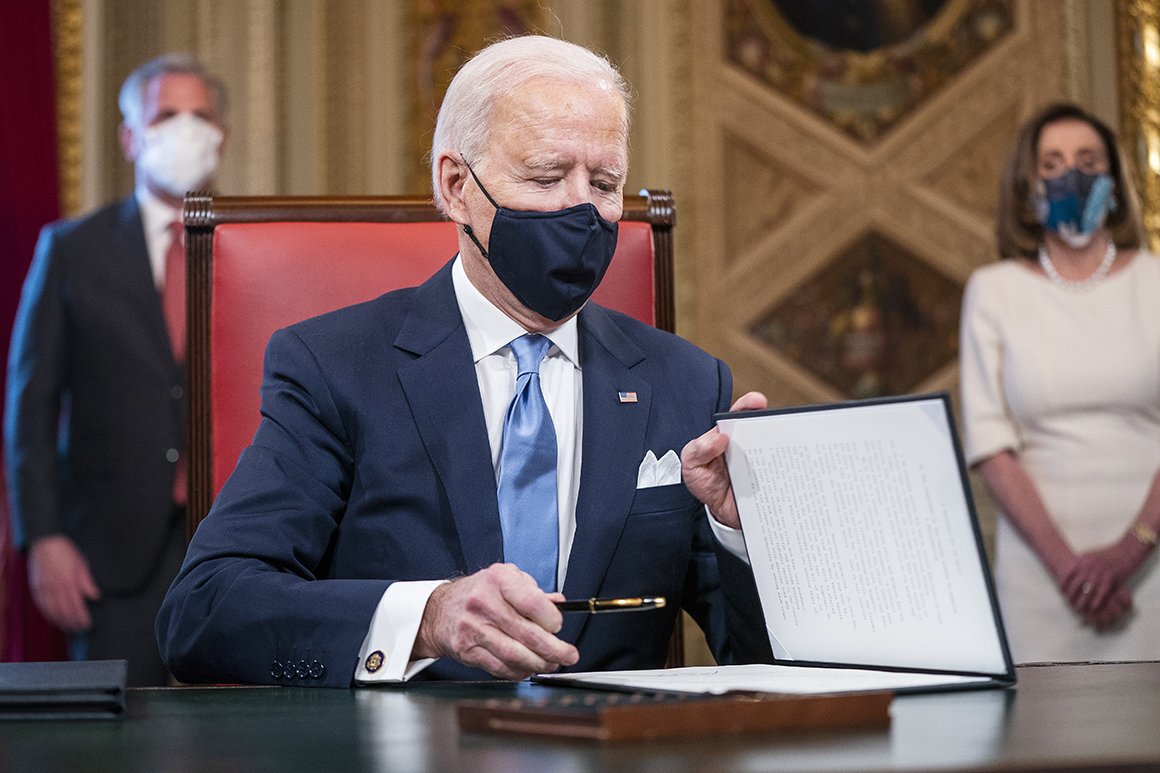

Though President Joe Biden rolled out a $1.9 trillion relief proposal last week, big questions have yet to be settled in the Capitol, including what exactly Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer will put forward, if Republicans will participate in negotiations or even when Congress will act. What Biden, Pelosi and Schumer decide — and how much GOP cooperation they get — will do much to shape the direction of Democrats’ first opportunity to govern in a decade.

“I can’t imagine a president coming under, coming in under more difficult circumstances,” Rep. Andy Kim (D-N.J.) told reporters just after the inauguration ceremony. “But I know it’s not just on him, you know, we got to do our part in the Congress.”

In recent days, Democrats on the Hill and incoming administration officials have been privately discussing several potential paths to bringing legislation to the floor quickly. One of the leading options is a powerful budgetary maneuver that would allow Democrats to evade a Senate filibuster and muscle their package through both chambers with virtually no support from Republicans.

But that tool — known as reconciliation — would be a divisive first move for a Biden administration insistent on bipartisanship. It’s also an imperfect process: any bill would likely be limited in scope to comply with strict budget rules, and Democratic leaders would have zero room for error to secure the 51 votes for passage in the Senate.

“I feel like that’s gotta be the very last resort,” Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi (D-Ill.) said in an interview Wednesday. “We’ve got to do everything we can to make this bipartisan.”

Some House Democrats are also eyeing another possible alternative: a bipartisan bill to dole out quick cash for vaccine distribution and $1,400 stimulus checks that would cost far less than the $1.9 trillion package that Biden initially sought. That path, those Democrats argue, would address two critical areas of relief and deliver a much-needed win in the early weeks of Biden’s term.

And some lawmakers in both parties are still holding out hope for a big, bipartisan bill that moves through both chambers quickly with enough Republican backing that Democrats could hold reconciliation in reserve. That would require support from at least 10 GOP senators to clear the Senate’s 60-vote threshold — an uncertain outcome.

Democrats are under pressure to move quickly, as Biden took office one day after the U.S. passed a devastating milestone of 400,000 people dead from the coronavirus and as the economy appears to stall. Lawmakers of both parties acknowledge a deadline of March 14, when the latest round of federal unemployment aid will expire.

Senior Democratic lawmakers and aides insist the lack of a final decision isn’t for lack of trying. Top staffers in the House and Senate have been meeting regularly with each other and Biden administration officials to figure out a plan for the coming weeks. And Biden administration officials have already started meeting with certain lawmakers, like moderate Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), to walk them through the White House’s relief plan.

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), who along with Murkowski was part of the bipartisan group of senators that helped jump-start the relief deal in December, said that coalition is setting up a broader coronavirus meeting with the administration in the coming days.

“We’re going to be meeting with them probably over the weekend,” Manchin told reporters Wednesday.

But Democrats also point to a perfect storm of disruptions that have upended Washington — a mob of armed insurrectionists trying to overrun the Capitol, a sudden, slightly unexpected turnover of control in the Senate and then the usual chaos that comes with any change in administrations.

In the House, the path of least resistance would be to move a smaller bill that focuses on vaccine distribution funding and stimulus checks — an idea some Democrats have said could get a vote as soon as next week and the potential for bipartisan buy-in.

“One of the things I think could really get people together is vaccine distribution … and maybe there’s some additional monetary assistance,” said Rep. Tom Reed (R-N.Y.), co-chair of the Problem Solvers Caucus. “Maybe there’s a conversation there to be had.”

But even moving a modest Covid relief bill through the Senate could be challenging given the chaotic atmosphere of the upper chamber. The Senate majority is changing hands, Biden’s Cabinet must be confirmed, and Senate leaders still need to establish an agreement for running a split Senate. Then there’s the looming impeachment trial for former President Donald Trump over his role in inciting the deadly riot at the Capitol, which will consume much of the Senate’s time.

And without unanimous consent, it could take several days for the chamber to even take up a House-passed bill. Many Republicans are skeptical of immediately passing a new relief measure after just approving a nearly trillion-dollar Covid bill in December. Congress passed roughly $3.5 trillion worth of aid in 2020 — a record amount as the U.S. response to the crisis continued to flail.

Several Democrats privately acknowledge that reconciliation is likely their best bet to delivering relief, unless Republicans can get on board quickly.

“If there’s a path to doing something bipartisan, obviously that’d be optimal. But people need help,” Rep. Derek Kilmer (D-Wash.) said in an interview. “I’m talking to people every day who are really hurting. And they can’t wait for more games in Washington, D.C.”

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Wednesday that Biden’s “clear preference” is to move forward with a bipartisan bill. But, she added, “We are also not going to take any tools off the table for how the House and Senate can get this urgent package done.”

Democrats are prepared to deploy reconciliation quickly if Biden’s package fails to garner enough GOP support.

“I think we’ve got to reach out to Republicans,” Senate Budget Chair Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) told reporters on Wednesday. “I hope many of them understand the crises that we’re facing. But if they don’t, we’ve got to go forward with reconciliation.”

House Budget Committee Chair John Yarmuth (D-Ky.) said he could set the gears in motion for reconciliation in a matter of days, if needed. He’s skeptical that Biden’s full plan would earn enough Republican support to totally avoid using it.

“We’re at that point where we can do whatever leadership says they want to do,” he said. “We’re prepared to use reconciliation for the relief package and we’re saving it for the relief package because that’s our number one priority, but we hope we don’t have to use it.”

Yarmuth said his staff has prepared for months and has closely analyzed Biden’s plan for potential violations of the so-called Byrd Rule, which restricts items in reconciliation legislation to items that affect federal spending and revenues. Certain items, like proposals to raise the minimum wage and paid family leave, may not pass muster and would have to be removed.

“Everything is on the table,” the Kentucky Democrat said.

Burgess Everett contributed to this report.