Democrats are eyeing trillions of dollars of new spending on the heels of their massive coronavirus bill. But some of their largesse has limits.

Even as President Joe Biden and his allies in Congress begin laying the groundwork for an infrastructure package whose price tag could top the $1.9 trillion bill he’ll sign this week, multiple Democratic centrists on both sides of the Capitol are ready to pump the brakes. They want at least some of the next big bill to be paid for, arguing there has to be some limit to Congress’s deficit spending as the nation claws its way out of Covid’s grip.

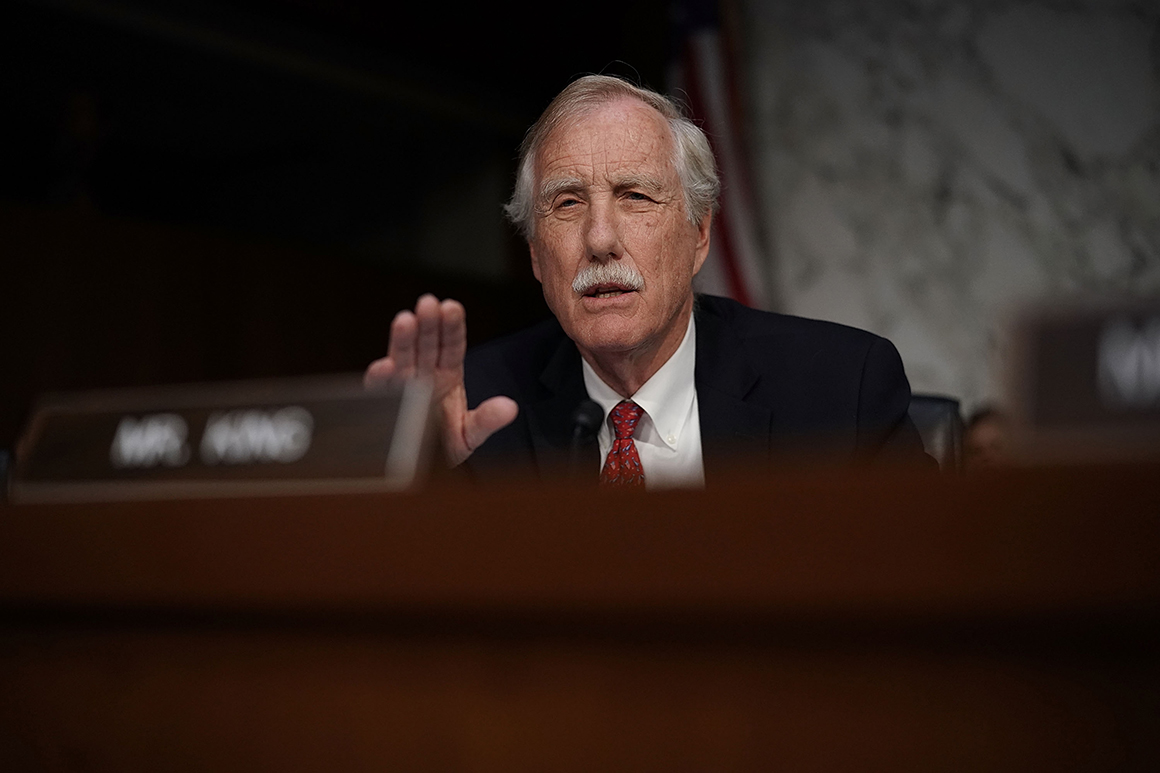

“At some point we’ve got to start paying for things,” said Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with the Democrats and is worried higher interest rates could become an albatross on the economy. “It’s got to be paid for. It’s just a question of who pays. Are we going to pay or our kids going to pay?”

Democrats — and Republicans, at least until Donald Trump left office — have shrugged off oceans of red ink over the past year as the U.S. confronted its worst public health crisis in a century. In just 12 months, Congress will have spent nearly $6 trillion fighting the virus and staving off economic free fall.

With an endpoint potentially coming into view, however, some moderate Democrats say it’s time for Congress to recover some semblance of fiscal pragmatism. That means Biden’s next major legislative priority can’t simply rack up more debt in a bid to remodel America’s crumbling physical infrastructure. And that could make things a lot tougher for Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“Some of it needs to be paid for,” said Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), who suggested an “all of the above” strategy for paying for an infrastructure package that includes spending cuts and raising new revenues.

“You’re going to remind me of this [later] when none of it’s paid for,” he deadpanned, “but I do think some of it needs to be paid for.”

Generating new revenue for infrastructure typically involves a debate about raising the federal gas tax, an idea so politically toxic that it’s been stagnant since 1993 and already repudiated by the Biden administration. Other ideas include charging fees based on the number of miles traveled, which raises privacy concerns with some politicians, or perhaps embracing unrelated tax increases on the wealthy to raise money for roads, rails and public transportation.

House Budget Chair John Yarmuth (D-Ky.) said Democrats are working under the “assumption” they’ll pay for at least some of an infrastructure measure, but he dismissed the idea that they could cover the entire cost.

“I think that’s unrealistic, given what everyone assumes the size of this is going to be,” Yarmuth said, noting that talks are ongoing.

Biden and top Democrats say they are committed to bringing Republicans on board for their plan. That bipartisan coordination would ensure the GOP helps carry the bill and sell it with the public.

But many senior Democrats are skeptical after such fierce opposition to Biden’s coronavirus plan. They don’t trust GOP leaders to be serious in the process, and they’re already in discussions about again using the budget reconciliation process to muscle through Biden’s next big bill on a party-line vote, sidestepping the risk of a Republican filibuster.

The president’s party is zeroing in on late May as a target date for bringing an infrastructure bill through committees in the House and Senate. Both Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.), chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, and Yarmuth said passage by September is the goal.

That task grows far trickier if a group of Democrats begins demanding some offsets for new infrastructure spending that could include portions of Biden’s clean energy agenda. Already, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has said he won’t consider another bill without at least trying to get GOP votes — though he’s also said he wants to pay for the plan by repealing Trump’s tax cuts for the wealthy, which Republicans would be loath to support.

And it’s not just Manchin.

“I think it’s time for everybody in this body, in the country, to start injecting that term back into the vernacular — ‘paid for,’” said Rep. Dean Phillips (D-Minn.), who added that he and other centrists are already in talks with top Democrats about the importance of paying for the next package.

“Well, I assume it’ll be paid for,” quipped Rep. Kurt Schrader (D-Ore.) when asked about the price tag for Biden’s next plan. “According to Democrat rules, the only thing we’re at liberty to put on our children’s credit card is Covid [relief] and climate change.”

But key figures in Biden’s Cabinet are envisioning a different approach. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, for instance, has signaled that he prefers deficit spending, telling POLITICO in a recent interview that "the opportunity and the constraints are just different when you have historically low interest rates."

Democrats are largely of the mind that going big is better than going small, trumpeting that they’ve learned their lessons from the Obama years about trimming their ambitions to cut a deal with Republicans. And they say there’s never been a crisis that warrants more spending than the pandemic, which has left 18 million Americans still out of work and as many as 10 million jobs permanently lost.

Even that appetite for a heap of federal aid will run out, though.

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) said economists have told her that recharging the system is more important than "the debt and deficit." But she added: “There would need to be revenues paid for some portions of it. I don’t think there’s an appetite for all deficit spending.”

Not all of the Democrats’ moderate members will demand cuts or new revenues to help pay for an infrastructure plan. Many are anxious to take advantage of what they see as the best chance to deliver on public works projects that Democrats have been promising for a decade — and Trump himself flirted with halfheartedly.

“There are some people who are concerned about rising debt … But at the same time, how long have we been talking about infrastructure?” said Rep. Lou Correa (D-Calif.), a senior member of the centrist Blue Dog Coalition. “I’ve been hearing that a very long time. And this appears to be a time when the stars appear to be aligned.”

Another Blue Dog centrist, Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D-Ariz.), said that "we want to try to see what we’re going to pay for."

"But in reality," he added, "we have to get people back to work. And we can’t just keep talking about infrastructure. We have to do it.”

Sam Mintz contributed to this report.