China has brought forward by two years its programme to launch a solar power plant in space that will beam energy back down to Earth.

A similar energy project had been proposed by NASA more than two decades ago but was never developed, while the UK government commissioned independent research supporting a £16bn British version in orbit by 2035.

The first launch for China‘s project is scheduled for 2028, when a trial satellite orbiting at a distance of around 400km (248 miles) will test the technology used to transmit energy from the power plant.

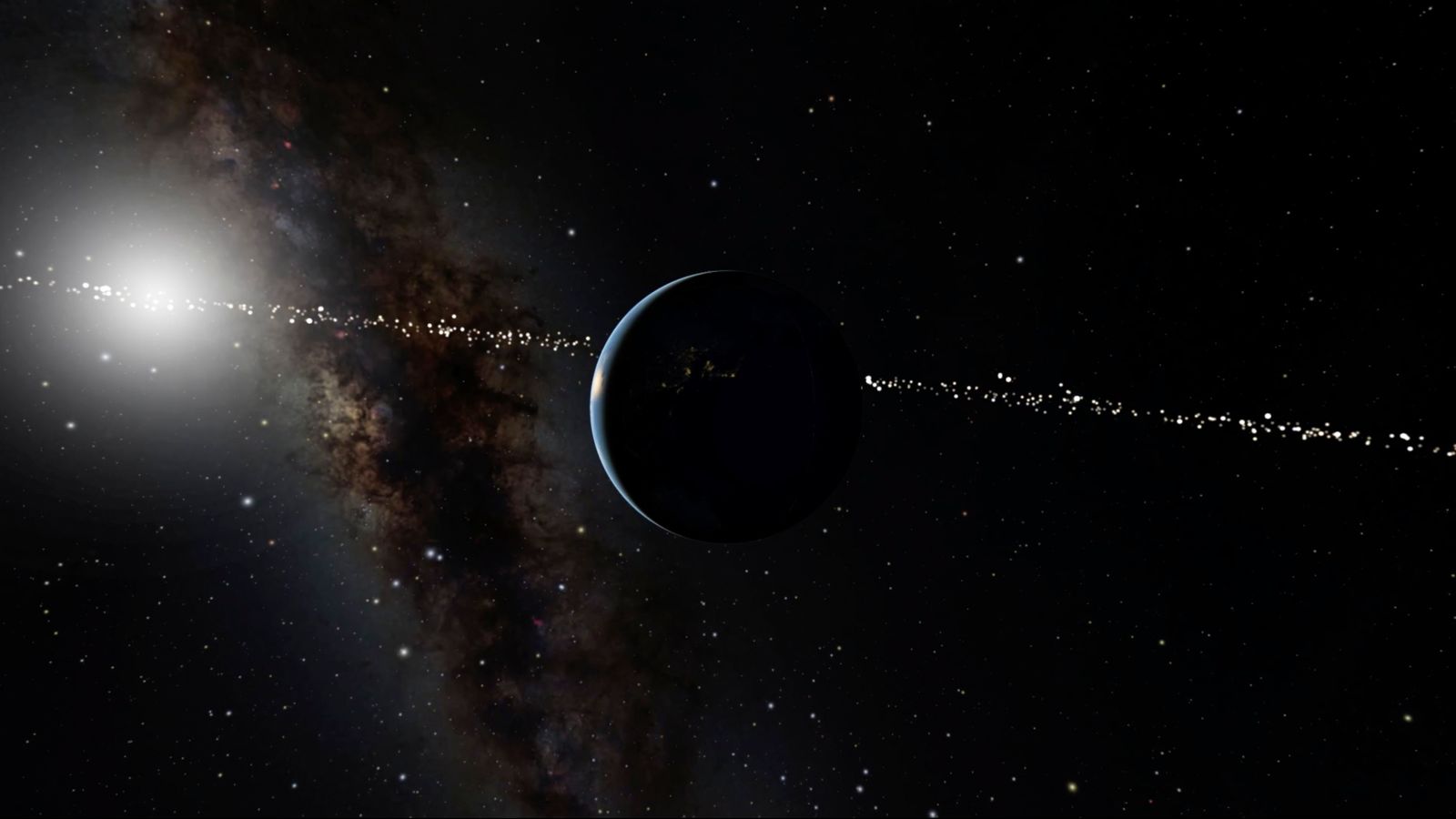

This satellite will “convert solar energy to microwaves or lasers and then direct the energy beams to various targets, including fixed locations on Earth and moving satellites” according to the South China Morning Post.

The plans were detailed in a peer-reviewed paper published in the journal Chinese Space Science and Technology.

According to the UK-funded research on space based solar power, satellites in geosynchronous orbit receive sunlight for more than 99% of the time – and at a much greater intensity than solar panels on Earth.

The idea is “collecting this abundant solar power in orbit, and beaming it securely to a fixed point” on Earth, said the UK-funded paper.

China launches three astronauts to complete its new space station

China’s most advanced aircraft carrier nears completion in ‘symbol of growing military might’

Ukraine says Russia attempting to move war to ‘protracted phase’ – after ‘achieving none of its strategic objectives’

These beams could also be directed to other nations “either as an energy export, or as part of our overseas development aid, or to support humanitarian disaster areas”.

Unlike terrestrial renewable energy sources, orbiting solar power plants would be able to deliver energy during day and night on Earth, at any time of year and regardless of the weather.

But there are significant engineering challenges that haven’t yet been solved, according to the Chinese paper’s author Professor Dong Shiwei.

Directing high-powered microwaves over significant distances would require an enormous antenna – potentially thousands of metres long – while solar winds, gravity, and satellite movement could interfere with the energy transmission.

The plan would see a large orbiting solar power space station built in four stages. Two years after the first test launch, in 2030, China would launch a more powerful plant to a geosynchronous orbit of 36,000km.

While the test station would have a 10 kilowatt power output, the bigger power plant would be able to distribute 10 megawatts to “certain military and civilian users” by 2035.

The technology would have advanced by 2050 – and the station would be big enough – to allow output of about two gigawatts, equivalent to the output of most of the UK’s terrestrial power plants.

This would mean the outposts would be commercially viable.

Read more: China launches three astronauts to complete new space station

Last year, a government research organisation in China outlined plans to design and build “ultra-large” spacecraft, potentially miles-wide, that would be assembled piecemeal in space.

Constructing large facilities in space has taken place before, with the ISS requiring 40 assembly flights and more than a decade to build.

But the enormous constructions proposed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China would eclipse the ISS considerably, which only measures 357 feet end-to-end, and could take decades and potentially centuries to build.

These constructions are described as “major strategic aerospace equipment for the future use of space resources, exploration of the mysteries of the universe, and long-term habitation in orbit,” by the NSFC.