For nearly 100 years, general elections have taken place on a Thursday, but the time of year has changed.

They mostly occur in spring or summer, but the last one in 2019 was held in December.

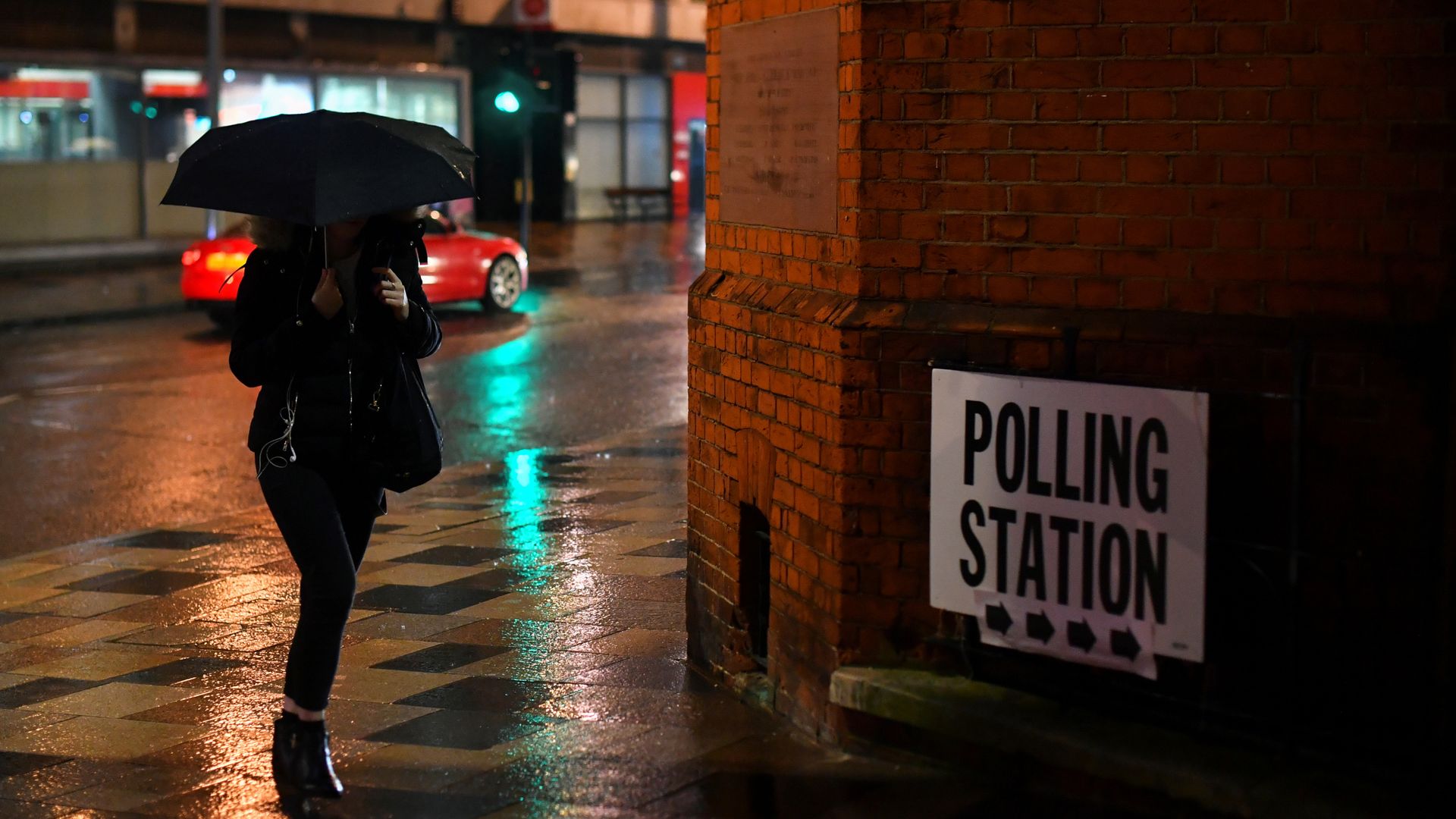

For that election, it was thought that turnout would be poor, due to the lack of daylight and potential for wintry conditions.

In fact, an article from the House of Commons library states that turnout in 2019 was 67.3%, down by only 1.5% compared to the June 2017 election when there was more than eight hours extra of daylight.

The article also mentions it was higher than the previous four elections all held in May or June.

Experts say there is no correlation between the weather and turnout at the polls.

So will the weather for the general election this year be as memorable as when the prime minister made the announcement in May.

Reform UK drops three candidates as racism row continues to engulf party

Election campaign trails: How party leaders are upping the ante as poll day looms

Faultlines: Eight-hour school runs and kids too hungry to sleep – the families caught up in housing ‘social cleansing’

It poured with rain as Rishi Sunak gave the election date, absolutely soaking him with no umbrella to hand.

With a week to go until the public head to the polling stations, it’s still a little too early to know the exact details of the weather.

Sky News spoke to Dr Robert Saunders, Reader in British History at Queen Mary University of London on the impact weather has on general elections.

“I suspect the weather has less impact on turnout than on the mood and character of the campaign.

“Jeremy Corbyn had great success with outdoor rallies in May 2017; that was a lot harder to do in December 2019, when it was cold, dark and miserable out.

“It’s not an accident that the Winter of Discontent in 1978-79 happened in one of the coldest winters of the decade, or that patience with wage restraint snapped among people who spent a lot of time outdoors: gravediggers, trying to dig frozen ground; lorry-drivers, sitting in unheated cabs; or bin men, collecting rubbish early in the morning.

“Likewise, the massive strikes of 1911 happened in the hottest summer since records began.

“They were particularly fierce among people doing physical jobs near hot machinery, like railway workers, or in the beating sun, like dock workers.

“So, the effect of the weather on polling day may be fairly minimal, but it can shape the mood of a campaign or the issues about which people feel strongly.”

Read more on Sky News:

Analysis – Sunak’s tetchiness over betting scandal speaks volumes

How will Britain’s ethnically diverse communities vote?

After the heat and sunshine seen this week, models suggest things will be more changeable at the start of July, perhaps wettest in the northwest, driest in the southeast.

Temperatures are likely to be around average for the time of year – the low 20s in the South, mid to high teens for the North.

👉 Tap here to follow Politics at Jack and Sam’s wherever you get your podcasts 👈

It certainly does not look to be as warm as the June 1970 election, when England, Wales and Scotland reached 28.3C, 27.8C and 26.9C respectively.

Keep up with all the latest news from the UK and around the world by following Sky News

Northern Ireland’s warmest general election was back in 1945, the last time the UK had a July election.

The wettest general elections were all in autumn or winter, but interestingly one of the snowiest was in May 1979, when Princetown in Devon had 13cm.