Members of the Congressional Black Caucus have a warning for Washington, D.C. lobbyists: Diversify your firms or you won’t have an audience with us.

Long a bastion of white men, K Street has found itself scrambling in recent years to up its representation of employees of color. But the threats from Black lawmakers to stop meetings with certain firms represents one of the most aggressive attempts to actually force K Street to change from within.

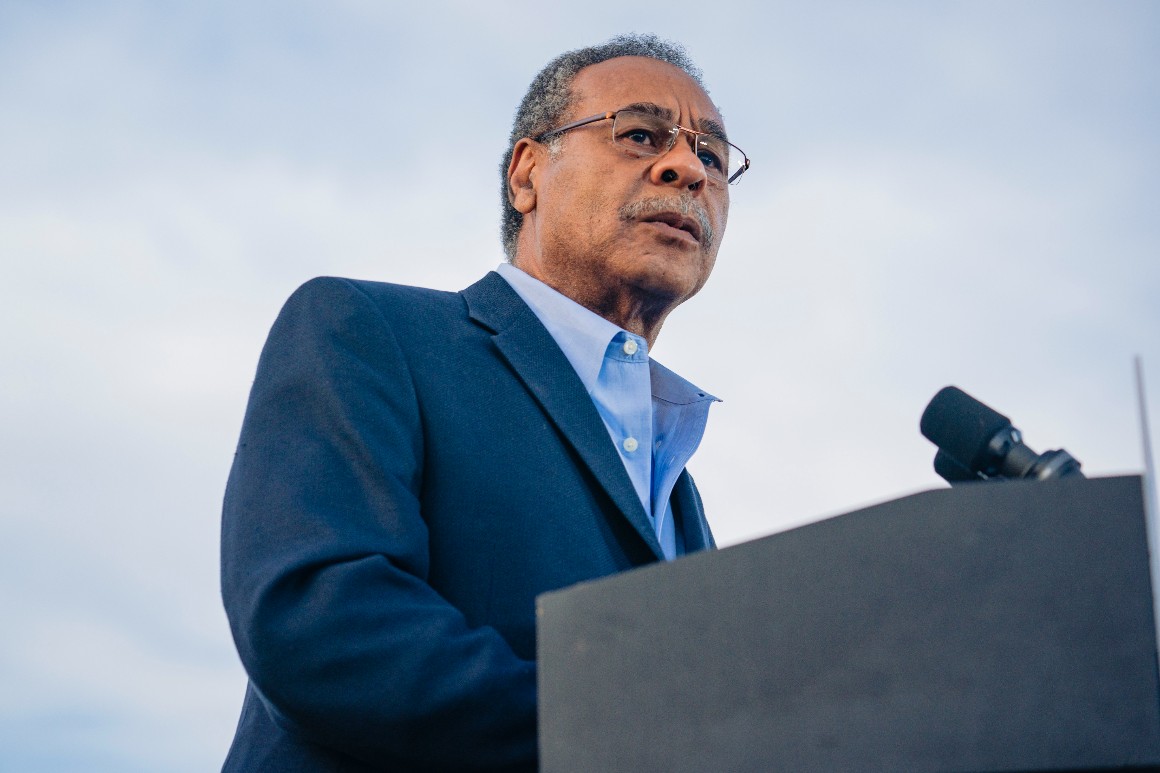

“We choose not to have any meetings with people who don’t have African American or Latino lobbyists,” Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D-Mo.) told POLITICO. “You got to be way out of it if you go into a meeting repeatedly with people of color, and you keep bringing three white men from Yale. It’s just, no.”

The Black Caucus has not taken a formal vote on whether or not to meet with companies or firms that lack Black male and female representation. But Cleaver said “the majority of the votes are already there for not meeting with them,” if anyone decided to hold a roll call at one of their weekly meetings.

The increasing power and sheer size of the Congressional Black Caucus in the Democratic Party makes it a formidable political force on and off the Hill. The caucus boasts more than 50 members and a number of committee chairs, along with the Democratic Party’s majority whip, Jim Clyburn of South Carolina (also a top Biden ally), and the House Democratic Caucus Chair Hakeem Jeffries of New York. For K Street, hiring lobbyists with connections to members of the caucus has become an increasingly integral part of a firms’ competitive strategy.

“If you need to hire somebody to lobby the CBC or the CHC or the Asian Pacific Caucus or whatever like yeah, absolutely, I think it makes a hundred percent sense that you hire somebody that represents that community,” said Ivan Zapien, practice leader for government relations at the law firm Hogan Lovells, who is Hispanic.

But diversity remains elusive. A survey published in April from the Public Affairs Council found that just 17 percent of the public affairs profession — a broad term that includes lobbying or government relations — were people of color; 23 percent of respondents reported that there were no people of color in their public affairs team. The survey had a small size of respondents. But a glance at websites for some of the top D.C. firms that include pictures of their staff shows that lobbyists of color are few and far between, especially among the firms’ leadership teams.

“I think the CBC is just kind of, they’re losing their patience because we’ve been talking about this for decades,” said Monica Almond, who co-founded the Diversity in Government Relations Coalition, which launched a demographic survey of the profession earlier this year.

The practice of not meeting with — or making their displeasure known to — firms that don’t have Black operatives in their top ranks is not entirely new. Sources and Cleaver said that Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) started putting firms on notice more than a decade ago. Thompson told corporate advocates who entered his office that if they returned, he wanted to see someone who was not white. His message was clear, he noted: If lobbyists or their clients expect to work with the veteran member, they better take his concerns seriously. Though Thompson says he has not outright denied a meeting for this reason, he hasn’t shied away from warnings.

“We would tell them, say well, ‘if this is your philosophy, you can’t come to my office,’” Thompson said. “Because you have to, if you’re going to represent your client and come to an African American and your workforce is all white, that’s disingenuous to the client you’re representing.”

Other members have followed suit. Two Democratic lobbyists and one person close to the Congressional Black Caucus confirmed that they had heard that members are refusing to meet with firms because of diversity concerns.

“Now, it’s widespread. I know it’s not everybody but it’s growing,” Cleaver said. “Why should we meet with you, you’re putting on display what you think about inclusion.”

Thompson said that his messages have had an effect. A number of lobbyists of color have told him that they found new clients because they knew that there would be “a problem” if their Hill advocacy team remained all white.

“We have to use the bully pulpit of opposition in Congress to say to those companies, if you want to continue to enjoy the support of people like me, you have to make sure that your workforce looks like America,” Thompson said.

The goal, ultimately, is not just to increase Black representation at major lobbying shops but to ensure that Black lobbyists get elevated to the top ranks. Without that, it can make it harder for those lobbyists to move on to high-ranking positions elsewhere and weakens pay equity, said a source familiar with CBC dynamics.

“It’s the ones that don’t have any African American lobbyists outside of the HR person, and the receptionist,” the source said of firms who are not welcome in some CBC offices.

Decades ago, Republicans pursued a similar strategy, with designs on helping elevate GOP operatives and reshaping K Street. Former Rep. Tom DeLay (R-Tex.) helped lead the effort to pressure business groups to hire Republican lobbyists right as the Republican party was retaking congressional power.

With Democrats now controlling Congress and D.C. at-large, firms where a significant proportion of their firms are people of color have seen a boom in business. Among them, theGROUP DC, which boasts on its website a “deep and abiding relationship with the Congressional Black Caucus” (and has ties to Biden), has seen an influx of 18 new federally-registered clients in 2021. Federal Street Strategies, whose chief strategist Paul Brathwaite served as the executive director of the Congressional Black Caucus, has taken on five new federally-registered clients in 2021 after picking up four each of the previous to years.

But the pressure for K Street to hire Black lobbyists isn’t just being driven by lawmakers on the Hill. The business community itself is pushing to diversify the ranks of people it hires to represent it in D.C., prompted by “clients who no longer want meetings with a bunch of old white guys,” said Ivan Adler, a professional lobbyist headhunter.

A “smart company” would find out who has the best relationship with powerful members, said Thompson. He added that it would be “stupid” for corporate interests not to maximize their chances of finding a friendly audience with those members by bringing someone to the table with whom the lawmakers could identify.

Ultimately, however, operatives trying to change the racial balance on K Street say that a more holistic approach is needed. To staff K Street with more diverse lobbyists, there needs to be a more diverse applicant pool making its way through the pipeline from Capitol Hill and the executive branch — where many lobbyists get their start.

“People who work in advocacy, lobbying, government affairs are, you know, if not exclusively white, predominantly white, and we ask ourselves, well why is this?,” said Doug Pinkham, president of the Public Affairs Council, which has worked with a group called College to Congress that provides funding and training for interns to eliminate barriers to entry to Hill internships. “Who becomes a Congressional staffer? Well, people who are Congressional interns … frankly a lot of white, well-to-do people.”