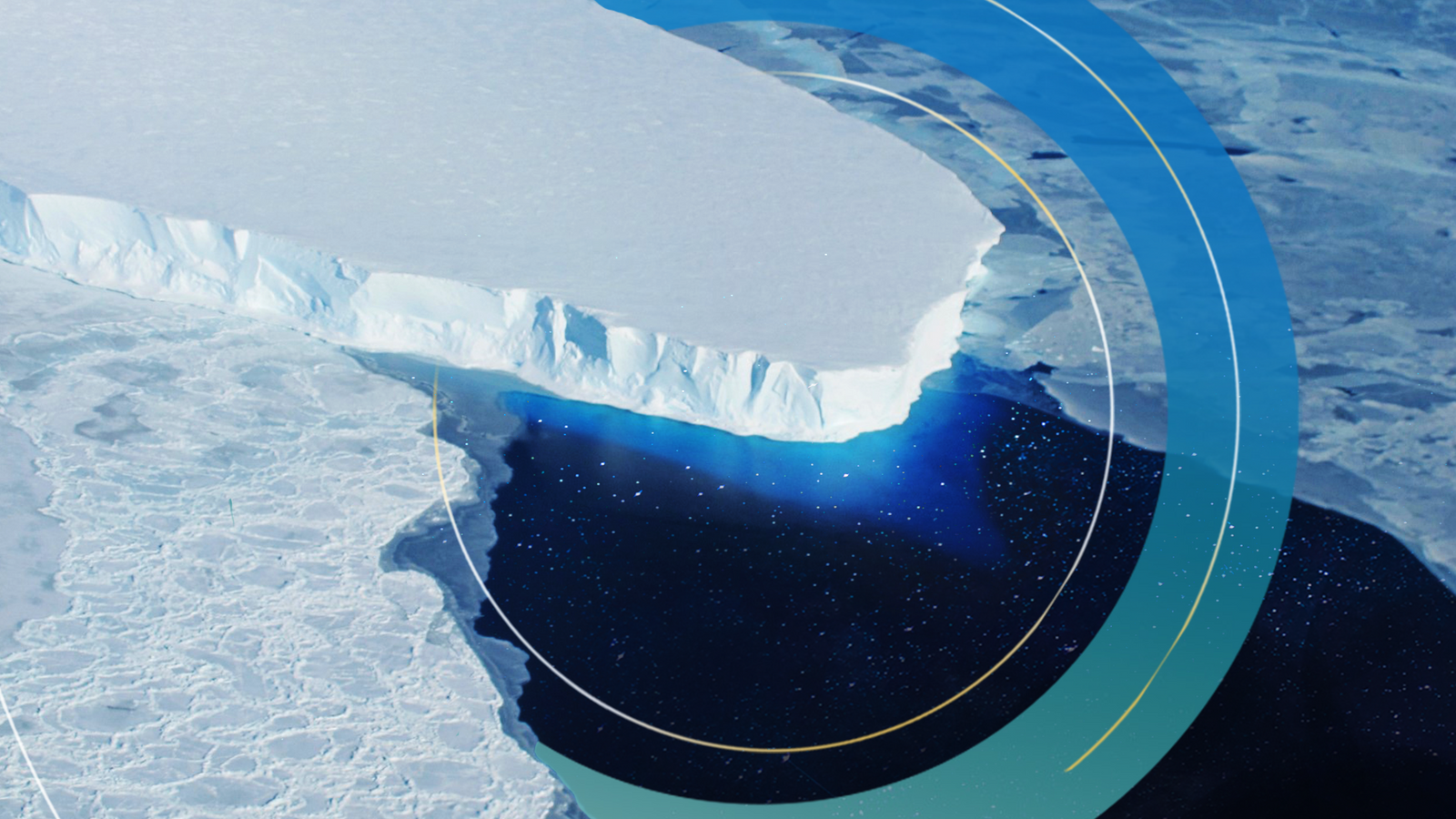

Every iceberg tells a story. Up close you can see how immense forces have twisted frozen layers as ice has shunted and scraped its way down a glacier over the centuries, then tumbled into the sea to slowly melt.

Bobbing in a boat next to one beauty, I once asked a glaciologist what it meant to see so much ice in the water.

“Don’t buy beachside property,” was his dry reply.

The Arctic and Antarctic seem a long way away. But the accelerating melt is going to affect us all, and not just those directly affected by rising sea levels.

The latest satellite assessments of sea ice are another sign of rapidly warming polar regions. In Antarctica, it has already shrunk to a record low, with still a few weeks left in the summer melting season.

Much of the coast is ice-free, and a lot of the ice that remains is thin and patchy.

Meanwhile, in the Arctic, the sea ice should be expanding and thickening at this time of year. But it too is tracking below both the long-term average ice cover and the previous record low year in 2012.

So both poles have low sea ice at the same time. What’s going on then?

The ice is being melted from above and below. Warm air and water are being brought into contact with the ice by changing winds and currents. It’s a trend that’s been clear in the Arctic since 1979.

Antarctic sea ice varies much more from year to year – but scientists are investigating a melting trend that seems to have started in 2016.

It matters of course to polar animals. Seals and walrus use sea ice as a platform to rest, narwhal and beluga use it to hide from killer whales, and polar bears use it to hunt. As the ice shrinks their habitat disappears.

But the ice also has impacts on the whole planet. When sea ice melts it doesn’t directly raise the water level, unlike ice calving off a glacier. The effect is indirect.

In Antarctica, the ice acts as a barrier between the destructive waves of the Southern Ocean and the vast glaciers that flow off the land and out over the water. With less ice, there is less protection.

The ice sheet that blankets West Antarctica is big enough to raise global sea levels by three metres, and the latest research on the perilous state of the Thwaites glacier, which is a Britain-sized chunk of it, is giving scientists sleepless nights.

Read more:

Mixed picture for ‘Doomsday’ Thwaites glacier revealed by scientists

How 2022 kept breaking new extreme weather records

Climate crisis may have triggered collapse of ancient Hittite empire

The increasing amount of cold, fresh meltwater from sea ice is also changing ocean currents that act as conveyor belts to help regulate global temperature.

Closer to home, in the Arctic, the disappearing sea ice is reducing the amount of the sun’s energy reflected off its bright white surface, accelerating warming in the region.

Click to subscribe to ClimateCast with Tom Heap wherever you get your podcasts

Some scientists believe that is altering the jet stream, increasing the chances of extreme weather in temperate regions like Europe.

It’s those extremes – drought, floods, heatwaves, and so on – that are the flashpoints of the climate crisis and rightly get lots of focus.

But changes to the underlying global systems – of which sea ice is a part – are just as worrying. They have the potential to tip us into an uncertain future.

Watch the Daily Climate Show at 3.30pm Monday to Friday, and The Climate Show with Tom Heap on Saturday and Sunday at 3.30pm and 7.30pm.

All on Sky News, on the Sky News website and app, on YouTube and Twitter.

The show investigates how global warming is changing our landscape and highlights solutions to the crisis.