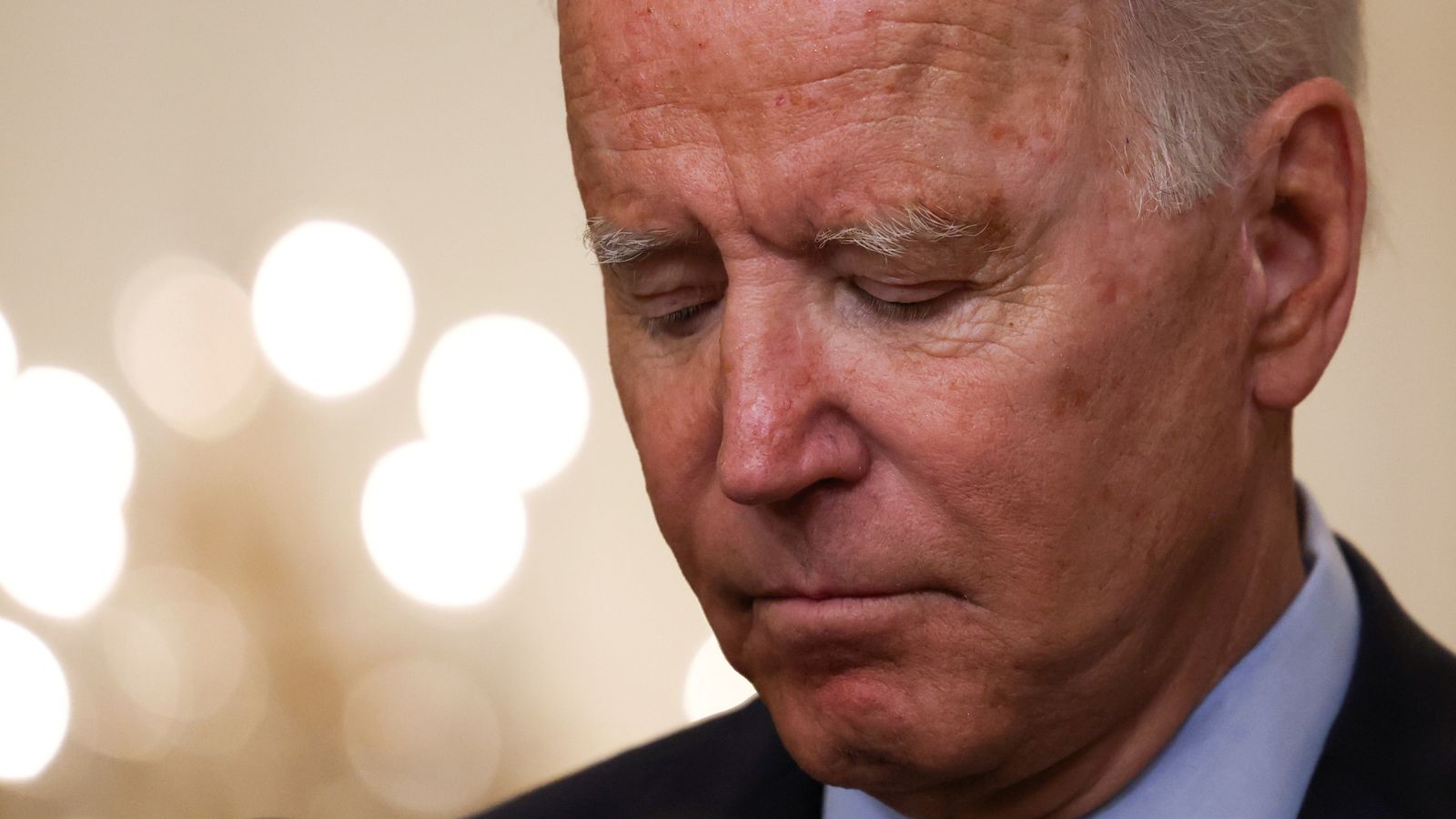

Just over a month ago, President Joe Biden was asked by a reporter if a Taliban takeover of Afghanistan was “inevitable”.

“No, it is not,” the president said.

“Why?”

“Because, you have, the Afghan troops have 300,000 well-equipped, as well-equipped as any army in the world, and an Air Force, against something like 75,000 Taliban. It is not inevitable.”

It has taken just four weeks for that statement to be proved so spectacularly and alarmingly wrong.

It was Donald Trump’s policy to end the war in Afghanistan; to pull the troops out. It was a popular decision and Joe Biden adopted the commitment, believing it would play well with voters here.

But the reality unfolding many thousands of miles away from Washington DC will now be on him.

Does he regret the decision? He was hardly visible as he departed for his weekend retreat at Camp David. He left it to an aide, in a written statement, to spell it out.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said: “The president is firmly focused on how we can continue to execute an orderly drawdown and protect our men and women serving in Afghanistan. You heard him earlier this week: he does not regret his decision.”

Charles Lister, senior fellow at Washington DC’s Middle East Institute, argues the decision is a “predicable calamity”.

“It’s kind of hard to believe there can’t be any regret, but there’s no way, I don’t think, he can ever express that. But I think there is no doubt that there is now a great deal of regret from people serving in the administration and from those who have recently departed from US government, on a bipartisan level, that this was a big mistake,” Mr Lister said.

He continued: “I think President Biden was elected into office in part to begin to withdraw from the so-called ‘forever wars’. In that sense, Afghanistan was low hanging fruit. It was the easy one to do. Of course, we’ve been there for 20 years and we certainly haven’t achieved all of our objectives. So he’s going to stick to that line.”

The president and his advisers had gambled that the years of training by US and coalition troops and billions of dollars of equipment would enable the Afghan government forces to stand up against any Taliban advance.

They also assumed that the Taliban were far less coordinated than they have turned out to be.

These two fundamentally important assumptions were wrong. And so what about the other assumption, that the Taliban leadership would, if they regained power, stick to commitments not to let al Qaeda and other terror groups return?

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Doug London is a former CIA operations officer and served as the US counterterrorism chief in south and southwest Asia, covering Afghanistan.

He said: “I would not be surprised to see al Qaeda members moving back to Afghanistan from Iraq where many of them sought refuge and sanctuary from counter terror pressure by the US, the UK and others and basically taking advantage of the opportunities to get back into the business of training, plotting and planning and using the facilities of Afghanistan to project power outwards.”

Of course that was precisely the reason that the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001. The Taliban had harboured al Qaeda as they planned the 9/11 attacks.

It is somewhat of an irony that Mr Biden chose the 20th anniversary of the attacks on New York and Washington, next month, as his deadline to bring all the troops home.

If the aim of his timing was, in any sense, an attempt to convey the message “job done”, then the images and stories that are likely to emerge from Afghanistan over the next few days and weeks will be awkward to say the least.

Yet, Mr London argues that the past 20 years in Afghanistan shouldn’t be seen as totally futile.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

He said: “I served the mission at the time which was focused on counter-terrorism. When I look back on the last 20 years, we have had incidents but not on the scale that we’ve had (before the 2001 invasion). To the degree that we went there to prevent terrorist operations, to degrade AQ, to secure strategic defeat and make it less of a daily threat, that mission was served.”

The president has spent this week avoiding any reference to Afghanistan, focusing instead on his domestic achievements – trumpeting the passing of a $1 trillion dollar infrastructure bill.

His passion, through his long career, has been foreign policy, but he knew that it was the domestic challenges that needed to come first. He was elected on a pledge to fix America and to “Build Back Better”.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

But what about his other pledge – that “America’s Back” on the global stage after four years of “America First” from Donald Trump?

“He came into office saying that America is back and this demonstratively is not the case on the ground in Afghanistan,” Charles Lister says.

“I think he also came into office trying to reheal and reunify America’s relationships with allies around the world. And now I think there’s a great deal of doubt about what it means to stand by America with these great big decisions.”

Mr Lister says: “The Biden administration, from day one, has talked all about great power politics. The idea that Afghanistan isn’t part of great power politics is completely insane.”

“The images we’re all seeing on the TV right now of US troops leaving, troops coming in to rescue our embassy personnel… You know, that doesn’t make the United States look like a great power worthy of competing with the likes of China, who, of course, is sitting back and watching all of this play out, worried, but also perfectly happy to see the United States humiliated.”