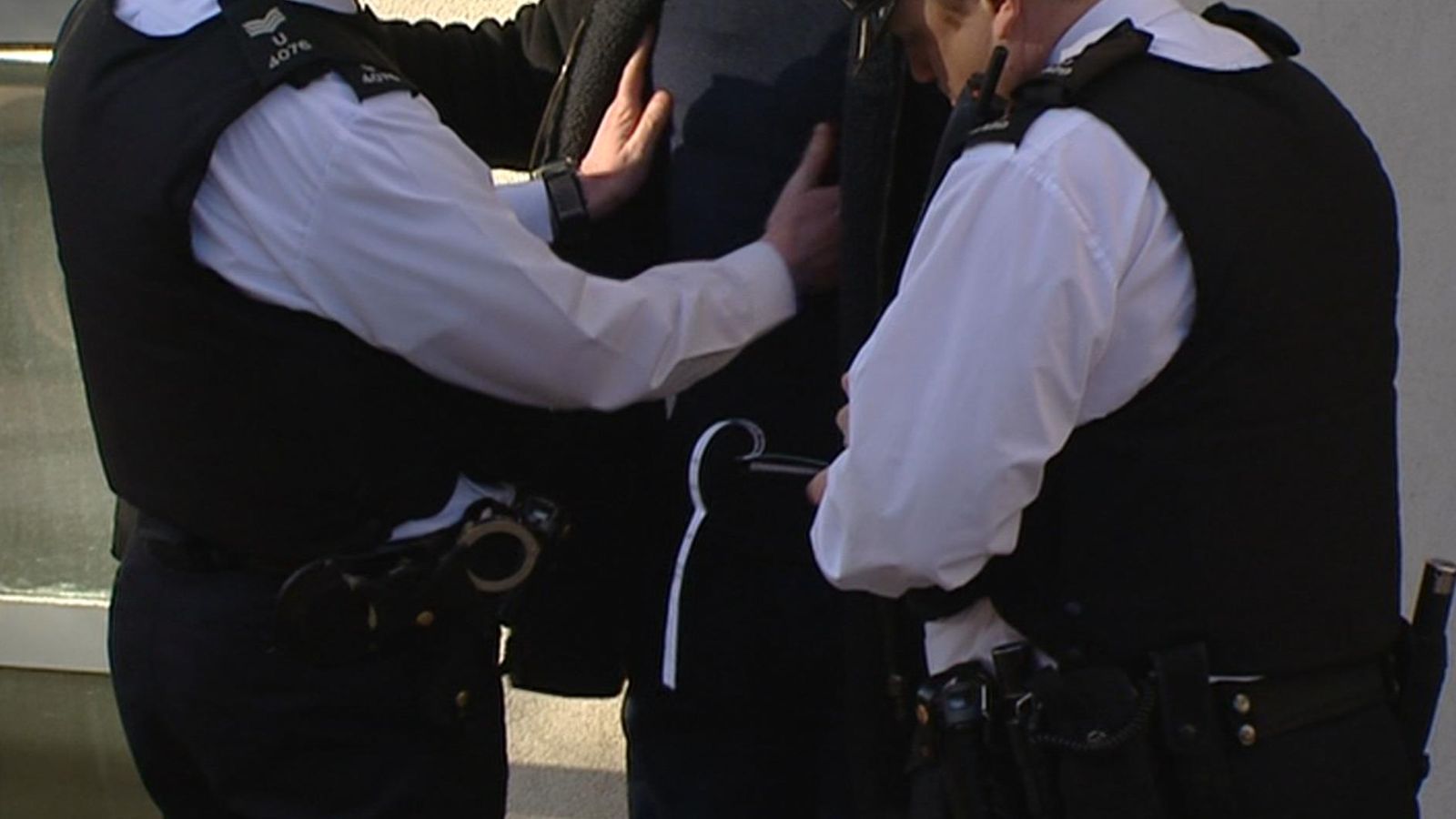

Stop and search has been described as a “rite of passage” for black boys – as a new report highlights the trauma it can cause.

It says a “perceived failure” to protect black communities, combined with negative experiences and stop and search practices, are behind black people’s “low trust” in police.

Research by criminal justice consultancy Crest Advisory found more than half of black adults who had been searched felt embarrassed and humiliated.

Despite it being such a contentious issue, the report found most adults actually supported the power, however, those who had been stopped were significantly less trusting of the police.

The survey of more than 5,000 adults found that across all ethnicities 49% of people stopped and searched trusted the police, compared with 65% for those who hadn’t been searched.

Some 61% of black adults stopped said they found it humiliating or embarrassing to some degree, compared with 49% for white adults.

“When we think about stop and search for black boys, it’s almost like a rite of passage,” said Sayce Holmes-Lewis, who founded mentoring organisation Mentivity.

Millions of Britons to receive £324 in their bank accounts from today to help with cost of living

Just Stop Oil protesters arrested in second day of M25 disruption

Rishi Sunak believes Sir Gavin Williamson’s account of events on the allegations he faces, No 10 says

Mr Holmes-Lewis has been stopped and searched more than 40 times in his lifetime, despite being a community leader and even sometimes training the Metropolitan Police.

When asked if he could share what it’s like, he paused, took a long deep breath and told Sky News: “Not everyone is able to overcome the trauma. How it makes them feel, being perceived as a criminal.”

He explained that stop and search often takes place in public places and passers-by assume the person being patted down is guilty.

‘You look like a criminal’

“It’s highly embarrassing. Having people look at you with disdain, just because you have been stopped – you look like a criminal,” said Mr Holmes-Lewis.

“Unfortunately that is the reality of a lot of black men doing great in their careers, young people engaged in education, no matter what you do there is a negative connotation of black people being criminal because of a narrative that we don’t control.”

The report found that while there is clear support for the use of stop and search in principle, including among black people, the police should not use it as a blank cheque.

Mr Holmes-Lewis agrees, and like many black people is extremely worried about the impact of crime on communities.

But he argues “stop and search under this guise is null and void” as it can cause more harm than good, worsening links between police and communities.

Harvey Redgrave, chief executive of Crest Advisory, said support for stop and search is “dependent on stops being conducted fairly, effectively and proportionately” but “currently this is not reflected in black people’s experience”.

“It is clear from our research that trust is the key,” he added.

“There are opportunities which could be grasped quickly if police strengthened relationships with communities, listened closely to their concerns and worked with them to tackle problems together.”

Confidence in police ‘far too low’

A spokesperson for the Police Race Action Plan admitted black people’s confidence in the police was “far too low” and needed to change in order to increase “legitimacy and effectiveness”.

“Chief Constables in England and Wales have signed up to the Race Action Plan as part of a commitment to improving policing for black people and becoming an anti-racist police service,” said Deputy Chief Constable Tyron Joyce, director for the Police Race Action Plan.

“One of the key actions in the plan is to ‘understand any disparity, seek to explain it or build a case for potential reform’ and develop a new national approach to help forces tackle race disparities in their use of powers, including stop and search.”

DCC Joyce reiterated that stop and search is a valuable tool but admitted it can have a “significant impact on individuals and communities, particularly on young people”.

He added: “It is our responsibility as leaders to ensure that we balance tackling crime with building trust and confidence in our communities, and we haven’t always got that balance right.”