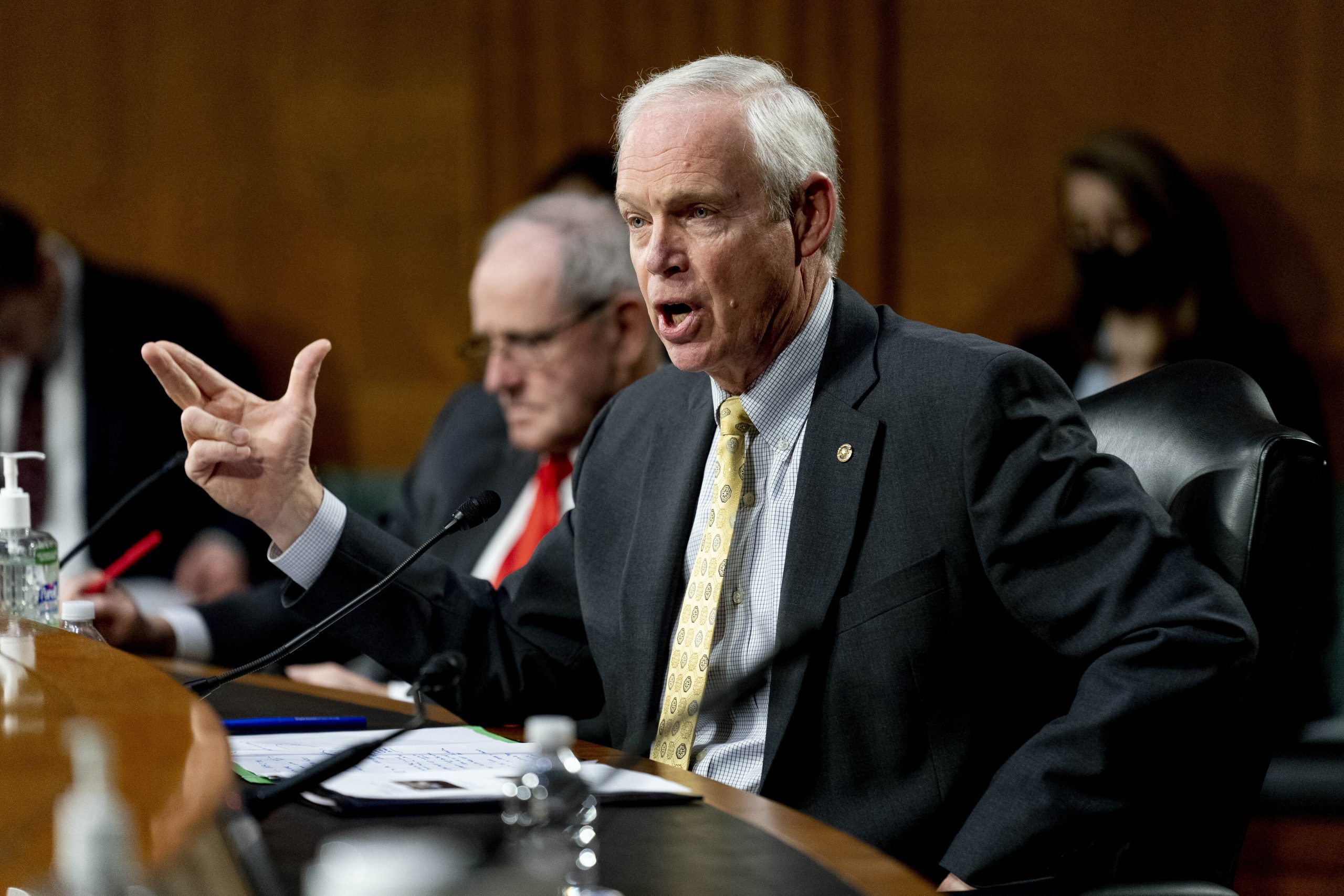

Ron Johnson could give Republicans the Senate majority this fall — though not without some headaches along the way.

The Wisconsin conservative is already a favorite foe for Democrats, thanks to his investigations into Hunter Biden and vehement distaste for Covid restrictions and vaccine mandates. And now he’s aligning himself with National Republican Senatorial Chair Rick Scott (R-Fla.), arguing their party needs to put up an affirmative agenda so it doesn’t fall on its face when it gets power.

In doing so, Johnson (R-Wis.) is castigating the GOP’s failed effort to repeal Obamacare in 2017 as little more than a plan based on a “slogan” while also reviving his complaints that he “wasn’t a real fan” of the party’s Trump-era tax cut bill because it didn’t simplify the system.

Though he’s not taking direct aim at Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, something he’s flirted with in the past, Johnson is clearly aligning himself with the Rick Scott wing of the party. Asked about McConnell’s Mutombo-style rejection of Scott’s plan last week, Johnson replied: “whatever.”

“I’m frustrated about everything about this place,” Johnson said of McConnell’s reluctance to thus far put forward an agenda. “Do I agree with everything in the Rick Scott plan? No. I don’t agree with anybody 100 percent of the time. I support him telling people what he’s for. I don’t see anything wrong with that.”

For McConnell, it’s the latest sign that his conference will probably be even more difficult to control a year from now, whether Republicans are in the majority or not. McConnell is losing several of his close allies to retirement this year, and the new crop of GOP senators will be more aligned with former President Donald Trump than those who are leaving.

A sizable number of McConnell’s members may run for president in 2024, with Scott considered a potential contender by many. What’s more, Sens. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) are favored to lead the GOP on the influential Commerce and HELP committees, respectively — a huge breakthrough for the party’s conservative wing and a potential vexation for McConnell.

And should he win reelection, Johnson will be a third-term senator with considerable sway on several key committees. Party leaders have learned to give Johnson considerable deference, trusting both his political instincts and the reality that he is a bull in a China shop — though one who usually supports his party in the end, like on that tax-cuts bill he still gripes about.

“He’s going to do it his way, but that way has worked. And so, in the end, we need him to win and we need him to hold that seat,” said Senate Minority Whip John Thune (R-S.D.). “If it requires him to chart sort of an independent path relative to what other candidates may be doing, so be it.”

Johnson’s political signature is shooting from the hip on whatever topic he is asked about. When asked about Scott’s proposed agenda, Johnson reaped a whirlwind of criticism for even broaching the subject of Obamacare repeal on Monday during an interview with Breitbart.

He said Tuesday he was merely using it as an example of how ill-prepared the GOP was to actually control the government in 2017.

“Repeal and replace, we weren’t ready for it, and we failed. And I was just using it as an example of how not to do it. I certainly wasn’t saying that should be one of our priorities,” Johnson said in an interview.

Nonetheless, he still fumes about the repeal debacle — which included him threatening to tank the entire thing on the Senate floor in 2017. And it’s no mystery who he still blames or why: “All leadership. They didn’t have a plan.”

Simply talking about repealing Obamacare is enough to provoke a cavalcade of criticism from Democrats, adding fuel to a fire Scott started by proposing all Americans pay income taxes. On the Senate floor on Tuesday, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said Scott and Johnson should create “a new ‘hurting working families caucus.’”

“Rick Scott and Ron Johnson have let voters know exactly what they can expect from a Republican Senate: higher taxes on seniors and working families, ending Medicare and Social Security, and a new effort to spike health care costs and gut coverage protections for pre-existing conditions,” said David Bergstein, a spokesperson for the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee.

Nonetheless, Johnson’s approach is a little more accommodating behind the scenes. Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) has traveled extensively with the Republican to places like Ukraine and said “privately I’ve always been able to get into much more interesting, nuanced conversations than people might think are available with him.” Murphy added that the conservative is not to be counted out in November.

“One thing I know about Ron is you underestimate him at your peril. I think he’s likely been constantly underestimated and bucked the political odds multiple times,” Murphy said.

Those miscalculations, by his opponents and colleagues alike, have shaped Johnson’s occasionally fractious relationship with his own party leaders. In 2016, McConnell wasn’t sure of the Wisconsinite’s reelection chances, as it appeared for months he would lose to former Sen. Russ Feingold (D-Wis.), and Republicans did not prioritize his race from the outset.

Since then, Johnson has shown little reluctance about speaking his mind, even if that puts him at odds with McConnell or any other Republican. He forced Senate clerks to read the entire 628-page American Rescue Plan, criticized the bipartisan infrastructure bill supported by 19 GOP senators as “crap” and now is voicing concerns about his party’s lack of a plan if it takes back power.

“I try and get along with everybody. But I’m not afraid to say what I believe,” Johnson said.

And he and Scott aren’t the only ones calling for the GOP to run on its own policy blueprint. In interviews this week, a couple more Republicans said that they wanted Senate Republicans to do more than just run as a foil to Senate Democrats. Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) said “when it comes to politics it’s hard to beat Mitch and his success rate,” but he’d like to see a more affirmative agenda.

“Between the two approaches, I lean more towards the Rick Scott approach to life,” said Sen. Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.).

Other than smacking down Scott’s idea to levy income taxes on more Americans and sunsetting federal laws after five years, McConnell has spoken only in generalities about the GOP agenda, should it win in November: inflation, energy, defense and crime. That’s enough for many Senate Republicans, who are eager to take their gavels back and obstruct Biden without a separate agenda that might become its own political liability.

“That’s an issue for 2024. It’s a question we really haven’t talked about. I’m really into 2022,” said Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), who is close to McConnell.

But that’s not enough for Johnson, whose reelection campaign could determine who is majority leader next year.

“I’m not afraid of a process to hone into what our top priorities ought to be and then be ready for them. You know, Democrats are always ready for this stuff,” Johnson said. “They plot for decades about how they are going to put us further down the road to socialism.”