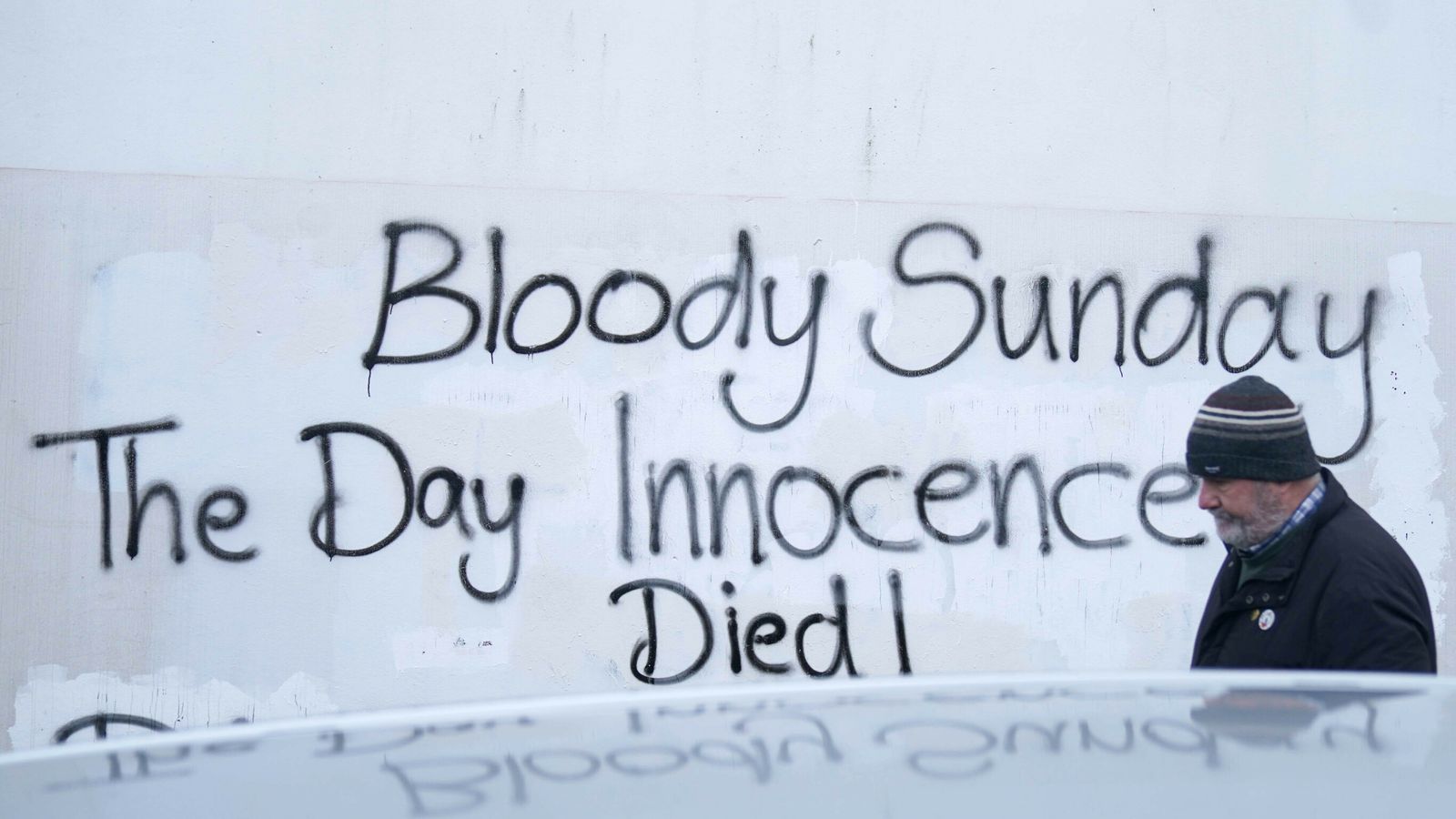

Relatives have marked the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday by rejecting British government plans to halt historical prosecutions in Northern Ireland.

They retraced the route of the civil rights march that took place in Londonderry on 30 January 1972 and remembered the loved ones who did not come home.

“My older brother Jackie, 17 years of age, taken away for nothing, shot running like myself that day, running for cover,” recalled Gerry Duddy.

Caroline O’Donnell, whose father was shot on Bloody Sunday, said they were still fighting for justice because “murder is murder”.

Thirteen people were shot dead and a 14th fatally wounded when members of the British Parachute Regiment opened fire that day.

Hundreds gathered around the modest Bloody Sunday monument in the Bogside, among them Ireland’s prime minister, Taoiseach Micheal Martin.

Having laid their wreaths, families stood in silence, but when it came to the government’s de-facto amnesty for veterans, they did not mince their words.

Victory for defiant Irish fishermen as Russia agrees to move its war games from their patch

Man charged after dead body of pensioner brought to post office in Ireland

Mental health: Irish father of three children killed by their mother calls for law reform

‘Please put up your hands’: Grieving sister appeals to soldier 50 years after Bloody Sunday

Mickey McKinney, whose lost his brother Gerard, said: “We send a very clear warning to the British government.

“If they pursue their proposals, the Bloody Sunday families will be ready to meet them head on.”

“We will not go away, and we will not be silenced,” he added.

Deputy First Minister Michelle O’Neill joined families on the march, along with the Sinn Fein leader, Mary Lou McDonald.

Mrs McDonald said: “It’s very humbling to be here in Derry 50 years on, generations on from that awful atrocity on that awful day.”

“Ironically, at the time when the British government now believes that they can grant an amnesty and impunity to their armed forces,” she added.

At the precise moment the first shot was fired on Bloody Sunday, relatives fell silent in the Millennium Forum theatre.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

The actor Adrian Dunbar, who hosted the memorial event, described Bloody Sunday as “a tragedy made worse by a travesty”.

He said: “Bloody Sunday, one of the darkest days since the foundation of Northern Ireland, Derry’s Sharpeville.

“A hammer-blow from a callous and cruel government designed to squeeze the sense of freedom out of the people of Derry and to choke the struggle for civil rights for all, regardless of political hue or persuasion.”

He commended the Bloody Sunday families, who received a standing ovation as the choir sang: “We shall overcome.”

Thirteen people were shot dead and a 14th fatally wounded after the British Army opened fire on crowds demonstrating in Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland, on Sunday 30 January 1972, against anti-Catholic discrimination.

It came at the start of the Troubles – years of conflict between Unionists, who are largely Protestant and want to remain part of the UK, and Nationalists, who are largely Catholic and want to be part of a united Ireland.

Stones were thrown, and paratroopers eventually tried to arrest as many as possible. Army documents show 21 soldiers fired a total of 108 live rounds.

The government announced an inquiry into Bloody Sunday the day afterwards. It largely cleared the Army of any blame and was branded a farce by victims’ families and their supporters.

In 1998, Tony Blair commissioned a new inquiry – it became the longest and most expensive public inquiry in British history, lasting until 2010 and costing around £200m.

It found Bloody Sunday protesters completely innocent and although there was “some firing by Republican paramilitaries”, the Army was considered responsible for the violence.

The police then spent years on new murder inquiries, but prosecutors concluded that only one solider, identified only as “Soldier F” could be charged.

Last year, two charges of murder and two of attempted murder were dropped, and the prosecution halted when evidence was deemed inadmissible.