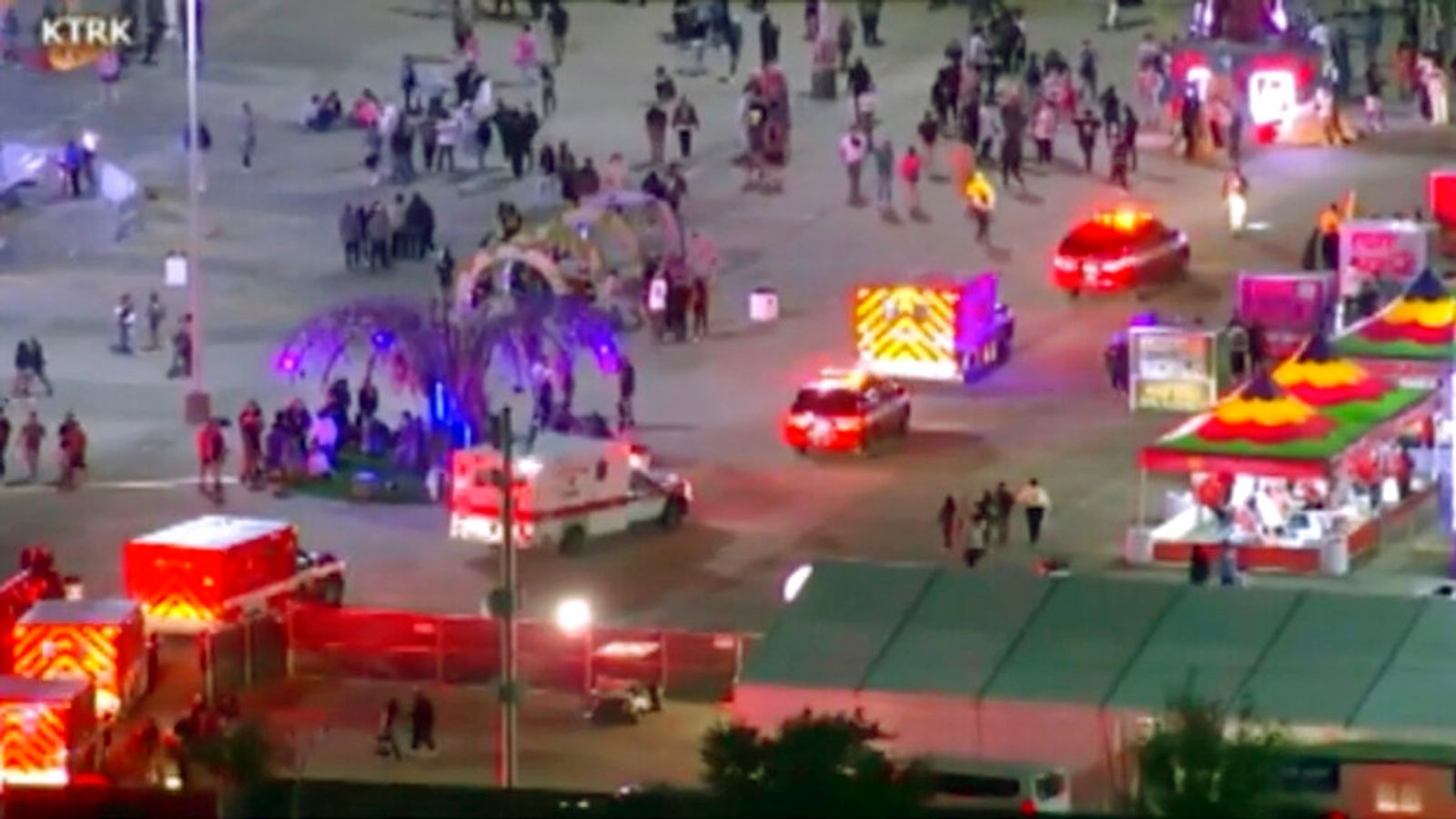

Police in Texas are investigating how eight people died and hundreds more were injured during a crowd surge at a Travis Scott concert in Houston.

Eight people, aged between 14 and 27, have been confirmed dead by their loved ones after the surge at the Astroworld Festival on Friday evening.

Investigators are expected to look at what crowd control measures and safety barriers were in place, using video footage and witness interviews, to establish why it happened.

Here Sky News looks at crowd surges, why they happen and how they can be deadly.

What do we know so far?

The incident occurred at around 9pm on 5 November ahead of rapper Travis Scott‘s performance at the two-day Astroworld Festival he founded at Houston’s NRG Park.

Around 50,000 people were in the crowd when a timer appeared on screens counting down to the start of the show.

Travis Scott sued after Astroworld Festival crowd surge tragedy in Texas – with lawsuit for $1m filed

Travis Scott concert deaths: Two best friends and ‘beautiful’ student named among victims of crowd surge at Astroworld Festival

Travis Scott releases video saying he is ‘devastated, as Kylie Jenner posts statement on Instagram

According to Houston Fire Department chief Samuel Pena: “The crowd began to compress towards the front of the stage, and that caused some panic, and it started causing some injuries.”

People then “began to fall out, become unconscious” causing “additional panic”, he added.

The show went ahead, but Scott stopped a number of times after spotting people in distress near the stage. “Security, somebody help real quick,” he said into his microphone.

Houston Police Chief Lieutenant Larry Satterwhite said the incident lasted just a few minutes, adding: “Suddenly we had several people down on the ground experiencing some type of cardiac arrest or medical episode.”

At this point, police asked organisers Live Nation to end the show early.

Families and friends have identified at least eight people who died at the concert, with more than 300 treated at a temporary medical facility on site, 25 taken to hospital and 13 still there on Sunday.

A criminal investigation has been launched, with police revealing over the weekend that a security officer was left unconscious after seemingly being injected in the neck.

Scott, 29, says he is fully cooperating with the authorities and his partner Kylie Jenner released a statement saying: “I want to make it clear we weren’t aware of any fatalities until the news came out after the show and in no world would have continued filming or performing.”

How do crowd surges happen?

Organisers of large events should have crowd management systems in place to ensure attendees have enough room to move around, enter and exit the venue safely.

If something unexpected happens and people move suddenly in one direction – for example towards the stage, exit barriers, or seeking cover from bad weather – there should be crowd calming procedures ready to stop a crush happening when they hit a barrier.

Professor Keith Still, an expert in crowd science at the University of Suffolk, has been called as an expert witness in several crowd safety cases in the UK, US and Europe.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Commenting on Friday’s incident, he told Sky News: “Looking at the video footage, I think we have a high-density, high-energy crowd and no show-stopping procedure in place.

“It has all the classic characteristics of a crowd surge – all the signs were there, they could have been acted on and this could have been prevented.”

Prof Still describes it as “all too typical in the events industry” and he said it is “beggars belief” that large-scale events are being organised “without the proper awareness” of crowd control.

The underlying cause of the event has not been established and an investigation is still ongoing.

Why wasn’t the show stopped sooner?

Although Scott briefly paused to tell security he could see fans in distress near the stage, his set still went ahead.

According to Prof Still “the authority to stop a show normally rests with one or two individuals”.

Ch Lt Satterwhite, of Houston Police, was involved in that decision.

“We immediately started doing CPR [on injured fans]… and that’s when I met with the promoters, and Live Nation, and they agreed to end early in the interested in public safety,” he said.

The criminal investigation now under way will look at whether the show-stopping order was taken soon enough.

Prof Still added that in his experience, staff who are in direct contact with the performer can often be “vague” in their instructions.

“That show-stopping process needs to be clear, laid down and understood by all,” he said.

Why are crowd surges deadly?

Although crowd surges are often referred to as “crushes”, Prof Still explains fatalities are usually caused by “suffocation rather than physical crushing”.

The inquiry into the 1989 Hillsborough disaster found asphyxiation to be the cause of several of the 97 victims’ deaths.

Others included “inhalation of stomach contents”.

Suffocation can either result from people being piled on top of each other vertically, pressed together horizontally, or pushed against a barrier – such as the tunnel and pens at Hillsborough.

At the 1971 Ibrox Park football tragedy in Glasgow that killed 66 people, police found enough bodies piled on top of one another to create the equivalent chest pressure of up to 64st (407kg).

Similarly at a Who concert in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1979 when 11 people died, lines of people 9m (30ft) long resulted in compressive asphyxia.

A US National Bureau of Standards study found that people pushing against railings or barriers can result in forces of between 30% and 75% of the weight of the person involved.

How do the authorities respond?

Houston police chief Troy Finner said late on Sunday that his team have launched a criminal investigation with homicide and narcotics detectives following the reports of a security officer being injected in the neck.

He said it was “too early to speculate” on the cause.

Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo has called for an “objective, independent” investigation of safety at the festival.

“Perhaps the plan were inadequate,” she said. “Perhaps the plans were good but they weren’t followed.”

Those pursuing justice for deaths at large events can pursue criminal and civil cases.

So far one concertgoer, Manuel Souza, has filed a civil lawsuit against Scott and organisers Live Nation, Reuters reports.

The petition, seen by the news agency, claims he suffered “serious bodily injuries” and is seeking damages of $1million (£741,000).

Another man named Kristian Paredes has also filed a lawsuit against Scott, Live Nation and the rapper Drake, who made a guest appearance at the concert, according to US media.

Prof Still says both civil and criminal investigations can take years due to the size of the events.

“When you’re dealing with mass fatalities and a large event, there could be hundreds of potential eye-witnesses,” he told Sky News.

“Every account needs to be heard and that’s why it often takes so long.”

He said that while criminal probes by the police are “more severe in terms of punishment” than civil claims by victims’ families, often civil litigation prevails and ends in a financial settlement out of court.

“With the events industry, it’s dealt with through litigation, which will take years and have a confidentiality agreement,” he said.

“This means court documents are sealed because of potential reputational damage and we never hear about it and therefore never learn from it.”

Sky News has contacted representatives for Scott and Live Nation for comment.

A spokesperson for Drake decline to comment on the lawsuit reports.

Has COVID made a difference?

Prof Still says that coronavirus has seen a “change in crowd behaviour” that event organisers need to “adapt to accordingly”.

He claims that emerging from lockdowns people tend to follow three main patterns of behaviour.

The “COVID cautious” still avoid large groups of people, while others respond by “celebrating” and having less regard for personal safety – or in a “contentious” way whereby they have “had enough” of restrictions and refuse to abide by them.

“At mass events, you tend to see more of that celebratory behaviour, with people being more exuberant and excitable,” he said.