The opening arguments at former President Donald Trump’s second impeachment trial kicked off with the most modern of evidence: a powerful video, spliced together largely from social media, forcing senators to relive the disturbing events of Jan. 6, 2021.

However, as advocates dove into the constitutional arguments, the assembled lawmakers soon found themselves being transported back in time to 18th-century England and even to ancient Greece and Rome.

Both sides trotted out historical examples to buttress their arguments on the pivotal, threshold issue occupying the trial’s first day: whether the Constitution allows for impeachment proceedings against Trump despite the fact that he is no longer in office.

House managers insisted that the precedents squarely favored their view. They invoked the case of William Belknap, a secretary of war who quit moments before the House impeached him back in 1876. The Senate held a trial for Belknap anyway, which Democrats consider powerful support for pressing on with the Trump impeachment even as he lives out the early weeks of his post-presidency in Florida.

“Many senators at that time, when they heard that argument, literally they were sitting in the same chairs you all are sitting in today,” Rep. Joe Neguse (D-Colo.) said. “They were outraged by that argument, outraged. You can read their comments in the record. They knew it was a dangerous, dangerous argument with dangerous implications. It would literally mean that a president could betray their country, leave office, and avoid impeachment and disqualification entirely.”

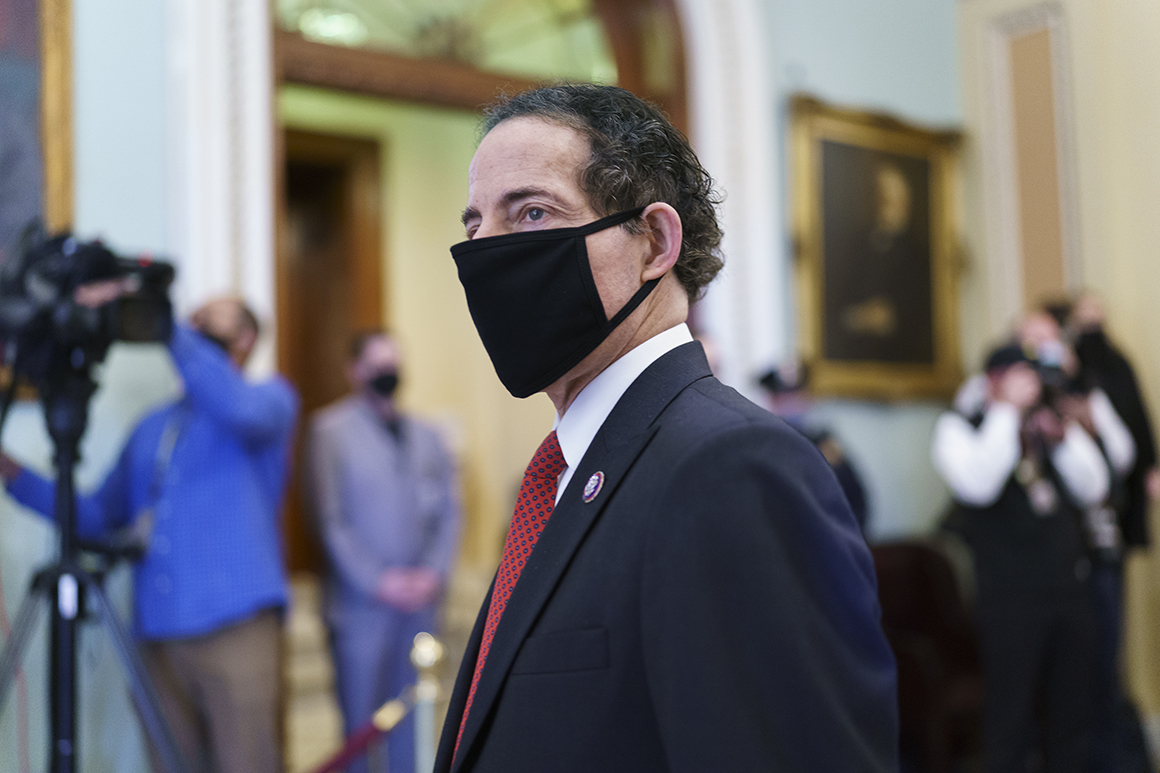

However, lead House manager Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) — a longtime constitutional law professor before being elected to the House — also jumped back almost a century earlier. Raskin used the same video screens that had just shown the Capitol riot to display a painting of Warren Hastings, a former British official in South Asia whose impeachment was underway as the Constitution was being debated.

“Every single impeachment of a government official that occurred during the framers’ lifetime concerned a former official,” Raskin argued. “The framers knew all about it and they strongly supported the impeachment. The Hastings case was invoked by name at the convention. It was the only specific impeachment case that they discussed at the convention. It played a key role in their adoption of the standard.”

Trump’s lead lawyer, Bruce Castor, was clearly listening. When he came to the lectern, he scoffed at Raskin’s analysis, arguing that most of the founders were not interested in emulating England.

“We have enshrined in the Constitution the concepts of liberty that we think are very critical, the very concepts of liberty that drove us to separate from Great Britain, and I can’t believe these fellows are quoting what happened pre-revolution as if that’s somehow a value to us,” Castor declared. “We left the British system. If we’re really going to use pre-revolutionary history in Great Britain, then the precedent is we have a parliament and we have a king. Is that the precedent we’re headed for?”

Castor wove in his own historical references, insisting that the senators could hasten the collapse of American civilization if they capitulate to the passions of the moment and vote to convict Trump or even to press on with a trial.

“The last time a body such as the United States Senate sat at the pinnacle of government with the responsibility that it has today, it was happening in Athens and it was happening in Rome. The form of republicanism throughout history has always and without exception fallen because of fights from within, because of partisanship from within, because of bickering from within,” warned Castor, a former district attorney from Pennsylvania.

“The greatest deliberative bodies, the senate of Greece sitting in Athens and the senate of Rome, the moment that they devolved into such partisanship. It’s not as though they ceased to exist. They ceased to exist as representative democracy, both replaced by totalitarianism,” Castor added.

While the history lesson may have bored some senators, it was surely more enervating than the grammar lesson Trump lawyer David Schoen offered, which involved parsing not only words like “the,” but also punctuation.

Schoen noted that the constitutional provision on impeachment says the punishment “shall not extend further than to removal of office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of Honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.”

“Ordinarily, an everyday English use of the conjunctive ‘and’ in a list means that all of the listed requirements must be satisfied while use of the ‘or’ means one of the listed requirements needs to be satisfied,” Schoen told the senators. If his sheer logic wasn’t convincing, the Trump attorney invoked the wisdom of Kenneth Starr, the former solicitor general who has been a reliable ally for Trump on a variety of legal issues.

“Judge Starr understands the comma to provide further support for the reading,” Schoen told the senators, who were silent but not rapt.

Many of Schoen’s arguments about principles of statutory interpretation seemed better suited to a legal brief than to an oral presentation to 100 senators. That appeared to dawn on the longtime civil rights attorney and regular Fox News commentator at one point as he sensed his audience growing restless.

“I know this is a lot to listen to at once — a lot of words,” Schoen said, sounding apologetic. “But words are what make our Constitution, quite frankly, and the interpretation of that Constitution, as you well know, is a product of words.”

The deep dive into history, grammar and canons of legal interpretation played out just minutes after Raskin seemed to promise senators they wouldn’t be subjected to academic digression.

“I know there are people dreading endless lectures about the Federalist Papers. Please breathe easy,” Raskin quipped. “I remember well W.H. Auden’s line that a professor is someone who speaks while other people are sleeping,”

The initial presentations from each side may have not taken all of that advice to heart, but Raskin clearly took measure of senators’ impatience following the Trump team’s two-hour-long presentation. Although the House managers had saved up 33 minutes for rebuttal, they chose not to belabor the point.

“Nothing could be more bipartisan than the desire to recess,” Raskin declared. “We waive all further arguments.”