For a moment, it looked like Donald Trump might be losing his iron grip on the GOP. In the wake of the deadly Capitol riot, 10 House Republicans joined Democrats in their vote to impeach him. Several other Republicans openly suggested at least censuring the president.

Not anymore.

Local and state Republican parties are censuring Republicans for disloyalty in states across the country. The lawmakers who broke with him are weathering a storm of criticism from Trump-adoring constituents at home, with punitive primary challenges already taking shape. In Washington, party leaders who once suggested Trump bore some responsibility for the Jan. 6 violence are backtracking.

On Tuesday, 45 Republican senators — all but five members of the GOP conference — voted that putting a former president on trial for impeachment is unconstitutional, all but guaranteeing the Senate won’t convict him. If the Republican Party seemed to be at a crossroads about its post-Trump future, it now appears to have concluded in which direction to travel.

“There is a level of support for this president more than during the election,” said Don Thrasher, chair of Kentucky’s Nelson County Republican Party, which recently voted to censure minority leader Mitch McConnell, a Kentuckian, for what Thrasher called “impugning the president’s honor” in debate over certifying the election results.

Of the post-presidential fervor for Trump, he said, “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The devotion to Trump, however, comes at great expense. The party risks tying its future to a one-term president whose deeply polarizing style cost the party both the House and the Senate during his four years in office. And he blew a hole in the party’s suburban foundation that might be irreparable.

Trump’s place in the party’s landscape appeared less certain after his November defeat and the Capitol insurrection that he helped to fuel with his false claims of a stolen election. Polls suggested Trump’s influence over the GOP was beginning to fade.

But the GOP is still a party in which Trump’s approval rating stands at about 80 percent. For Trump loyalists, Trump’s second impeachment has been taken less as an indictment of the former president’s behavior than a cause to rally around him — a martyr for an aggrieved populist base.

“There are 74 million people who voted for him,” said Charlie Gerow, a Pennsylvania-based Republican strategist. “You’re not going to get a mass exodus … At the grassroots level, he’s very, very popular, and I think the party as a whole understands that in order to be a majority party, it’s going to have to include those Trump enthusiasts.”

The real question now may not be how long Trump looms over the GOP, but whether there is room beneath his shadow for anyone else.

In Washington state, several Republican Party county chairs called Monday for the resignation of Republican Rep. Dan Newhouse, who voted for impeachment. The Republican Party of Oregon formally condemned “the betrayal” of the 10 House members who voted to impeach. Over the weekend, Arizona Republicans, despite watching their party founder during the Trump era, voted to censure Cindy McCain, former Sen. Jeff Flake and Gov. Doug Ducey, while reelecting a Trump loyalist, Kelli Ward, as state party chair.

And in Wyoming — a state that went 70 percent for Trump in November — the Republican Party of Carbon County voted to censure the state’s representative, Liz Cheney, for her vote to impeach Trump.

Joey Correnti, the Carbon County chair, ranked Trump in his “top five” presidents of all time.

As for the GOP’s posture toward the former president, he said, “If you’re going to receive the benefit of the brand, you ride with the brand.”

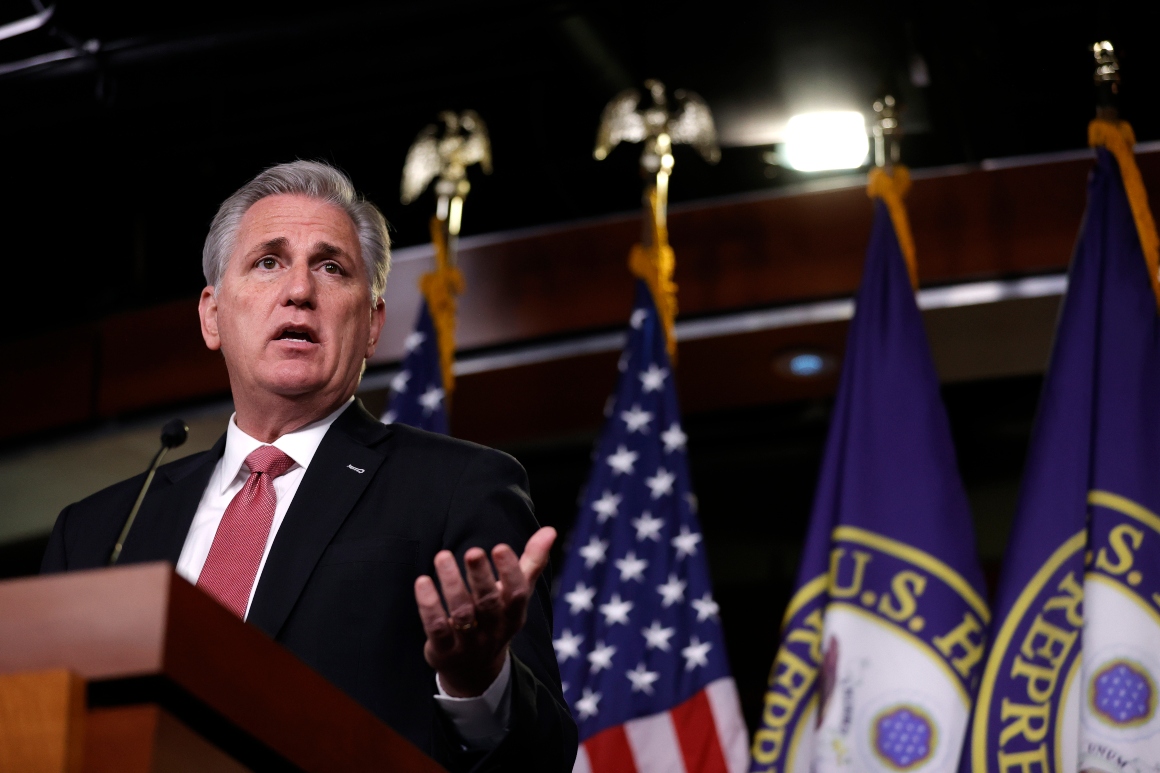

In recent weeks, the party’s governing class appears to have taken note of the base’s sustained fealty to Trump — and the impact it could have on their own political prospects. House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy said after the insurrection at the Capitol that Trump bore some responsibility for the riot. But then the California Republican said “everybody across this country has some responsibility,” and he otherwise labored to mend his relationship with Trump.

Nor are the Republican Party’s leading contenders for president in 2024 eager to cross Trump. Former U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley lit into Trump following the Capitol riot, telling Republican National Committee members that his “actions since Election Day will be judged harshly by history.”

More recently, on Fox News, she said, “I don’t even think there’s a basis for impeachment.”

“At some point, I mean, give the man a break,” Haley said. “I mean, move on.”

Many traditionalist Republicans are hoping that’s exactly what GOP voters will do. Republicans down-ballot were more successful than Trump in the November election. Scores of Republican voters cast ballots for candidates not named Trump — and do not concern themselves with the local party operations that are fuming at more moderate Republicans.

“The crackpot base that are Trump’s people, that are Trump’s wing men and wing women, will never leave him,” said Barrett Marson, a Republican political strategist in Arizona. But though “Trump still has a hold on the core base of Republicans,” Marson said, “In the larger Republican Party, that is not the case.”

Still, the most Trumpian, activist wing of the party controls many state and county party operations. And the once-fringe forces unleashed during the Trump era have metastasized within the party.

Millions of Republicans bought into Trump’s lie that the November election was stolen from him, with a large majority of Republicans saying after the election that they did not think it was free or fair. In Hawaii, a Republican Party official resigned recently after posting tweets sympathetic to subscribers to the QAnon conspiracy theory. The Texas Republican Party continues to use the “We are the storm” slogan, despite criticism about the phrase’s links to QAnon [The party has denied a connection].

Sean Walsh, a Republican strategist who worked in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush White Houses, suggested Trump’s pull on the party was so great that “you have to ease out of Donald Trump.”

“Many in the party kind of quietly hope that he goes away, and they can transition to the future,” Walsh said.

However, he said, “Elections are decided on such a thin margin in states, you don’t have to make too many activists angry to where it has a real meaningful and life-altering impact on your electoral future if you’re a politician. Darwin and politics are very similar: You have to survive to move on. And you can’t survive if you go out and dump on Trump hard.”

For Republicans who bucked Trump and faced recriminations from within the party, that has been the lesson of the last three weeks. Trump, despite his departure from Washington, remains close to the center of the GOP political universe.

Solomon Yue, the Republican national committee person from Oregon who pushed the resolution in his state condemning the 10 impeachment-supporting House Republicans, described the Republicans’ pro-impeachment vote as reflecting a lack of courage, which he said is “not made out of chickens—.”

Like other Trump supporters, Yue suspects Trump’s stature in the party will only improve over time, as Republicans who held off voting for Trump recoil from the Democratic agenda advanced by Joe Biden.

In Kentucky, where McConnell is the godfather of the state party, he nevertheless faced the prospect Saturday of a resolution urging him to oppose impeachment. While the state party ruled it out of order, the mere challenge to his authority raised eyebrows. And he was still taking flak at the county level, where Thrasher said he has been coordinating with other county chairs on a measure to rebuke him. The chair of a neighboring county party told Thrasher one of his constituents, an elderly woman supportive of Trump, asked if they couldn’t have McConnell “tarred and feathered,” while volunteering to “pour on the tar” herself.

Trump has kept an unusually low profile since leaving office, but he has indicated a desire to remain a force in Republican politics. If he rises up — whether supporting pro-Trump Republicans in primaries in 2022 or as a candidate himself in 2024 — whole swaths of the party may bend at his direction.

Trump “can intervene in pretty much any state operation — or at least 90 percent of the states,” Thrasher said. “If he interjected himself in any of the state party elections, it would go in his favor … I know in Kentucky, if he called for the removal of the whole apparatus, we’d vote them out.”