It all sounds dreadfully familiar. As the summer ends and the autumn term approaches, cases of COVID-19 are rising.

We all know what happened next last winter: cases rose through the roof, as did deaths. The winter wave of this pandemic turned out to be considerably worse than the first wave in the spring.

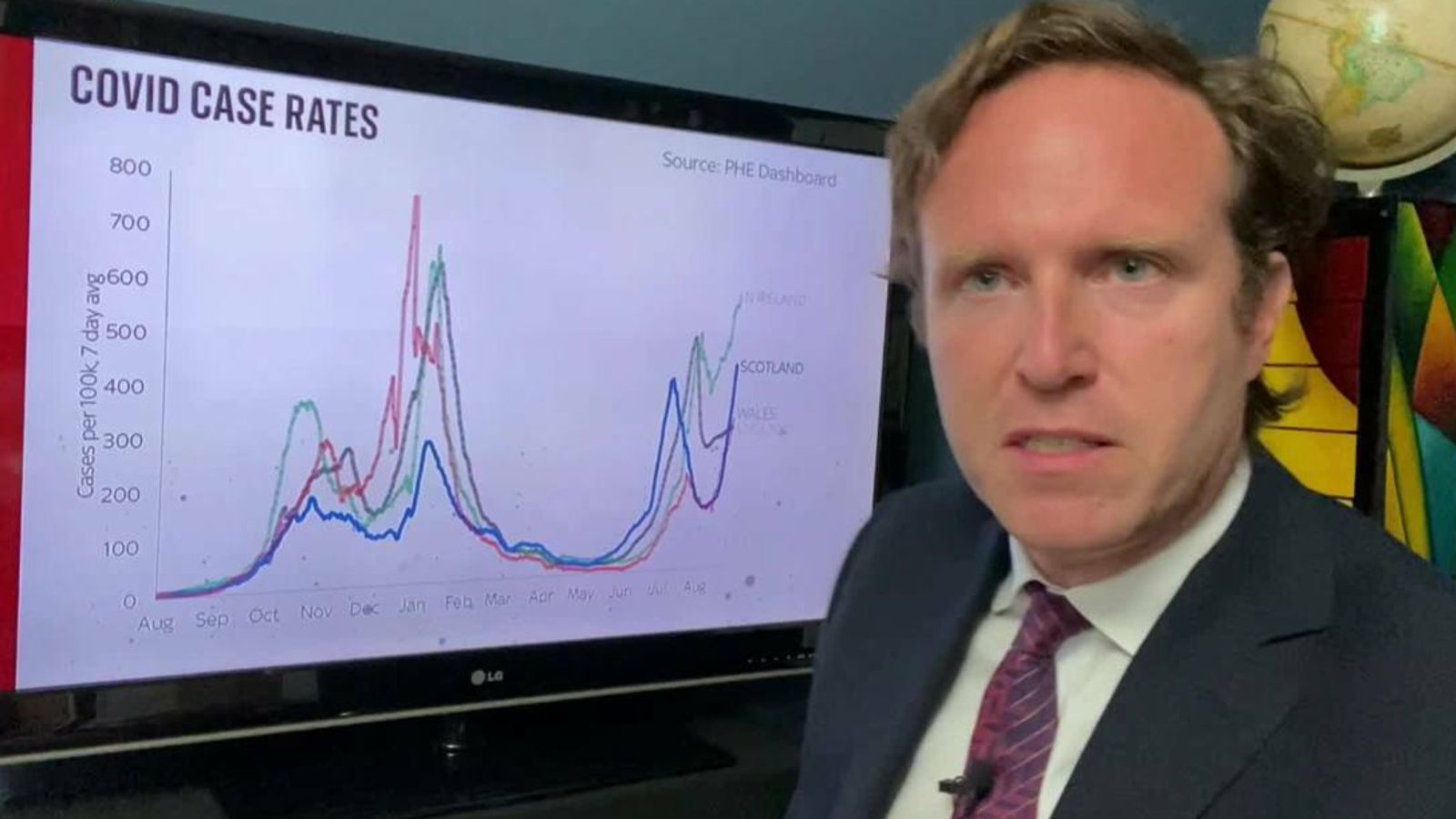

This time around, with school holidays about to come to an end in most of the UK, cases are at an even higher level than they were last August. So too are hospitalisations. So is it time to panic?

The short answer is no: it still looks as if the vaccination programme is doing precisely what was hoped for, but that doesn’t mean the next few months won’t be somewhat nerve-wracking: cases are likely to get even higher, as are hospitalisations, and deaths will surely creep higher still.

But crucially, the relationship between cases and deaths remains very different to how it was this time last year; that is perhaps the best news that could be hoped for.

Let’s start with the data on cases. Numbers are certainly on the rise. The latest daily figure reported by Public Health England was 38,281, and while cases across the UK are below their July peak, that may not be the case for long.

Indeed, in Scotland, case numbers (and the rate of cases per 100,000 of the population) is at the highest level on record.

In Northern Ireland, the case rates are higher still. In Scotland’s case, some have put this surge in numbers down to the fact that most of its pupils have returned to school before the rest of the UK.

But break down Scottish case rates by age group and a somewhat confounding picture emerges.

Certainly, the highest case rates are to be found among those aged between 15 and 19. But the case rates among the youngest age group, zero to 14, is actually quite low in comparison to most other age groups.

COVID rates among 20 to 24-year-olds, on the other hand, are almost as high as among teenagers.

As with all data, it’s hard to draw firm conclusions, but it looks somewhat more likely that these high case rates are more a reflection of teenagers and early twenty-somethings socialising than a return to school.

That suggests that there is considerably further that these case rates could rise, since we know from previous experience that the beginning of term often pushes numbers higher.

So don’t be surprised if case levels in Scotland and indeed the rest of the UK rise in the coming weeks.

But how much does that matter? For in the post-vaccination era, what matters even more than case data is what’s happening to hospitalisations and with deaths. So what is the story there?

The short answer is that while both are creeping up, they remain a long way below their winter levels. Hospitalisations in England are close to the July peak; in Scotland they are well short of that.

Across the UK, the daily deaths figures are rising. Of the past ten days, eight has seen reported death totals of over 100.

These numbers are certainly not trivial, and each death is a tragedy for a group of family and friends. But the crucial thing to note is that the levels are considerably below where they were the last time cases were this high.

Consider: right now the seven-day average of cases in the UK is running at just over 34,000 a day.

Back in winter when case numbers passed that point, the seven day average of deaths was running at over 500 a day.

Today it is running at just over 100, in other words, it’s five times lower than in the previous winter wave. And if anything this is an understatement of the scale of difference, given deaths tend to lag cases by a couple of weeks, and that level of cases was roughly associated with around 700 deaths.

In other words, the data is still telling a tentatively encouraging story. But (there’s always a but) we remain in uncharted territory.

We don’t know how well antibody levels will hold up in the coming months. It’s hard to judge the likely impact of schools returning.

What will happen when the weather gets colder and people spend more time inside?

On the flip side, there are more people vaccinated now, and an ever-increasing cohort of people (both vaccinated and not) who have caught and recovered from COVID, which means the country’s combined resistance to COVID is considerably higher than in all previous episodes.

The upshot is that the coming months will be another test of nerves, for policymakers, if not the rest of us.