Democrats are scrambling to find a path forward to reforming the military justice system, as lawmakers split over the best way to address serious crimes — primarily sexual assault — within the ranks and tackle racial disparities in military courts.

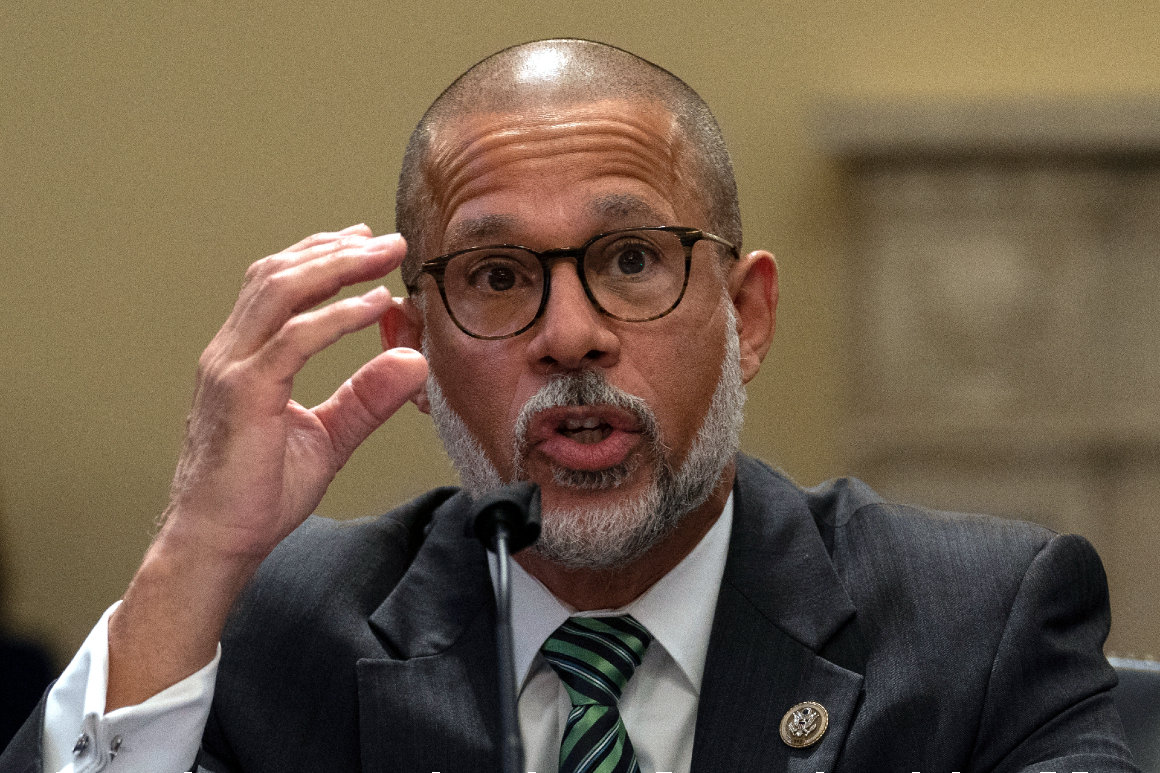

House Armed Services Committee Democratic members disagree on a central tenet of the bill — removing commanders’ authority to prosecute all serious crimes, beyond just sexual assault. Proponents of that change, such as Reps. Anthony Brown (D-Md.) and Jackie Speier (D-Calif.), say it would be a much-needed reform for U.S. service members of color, who have long faced disproportionate consequences in military courts.

“If you are a young black airman, you are twice as likely to be sent to court martial for the same offense conducted by a white airman,” Brown, who is Black and a 30-year Army veteran, told members in a closed-door caucus meeting, according to people listening. “Now is the time for Congress to step up.”

But the push by Brown and others has led to furious clambering behind the scenes by Pentagon officials, including Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who have strongly opposed the change, according to several people familiar with the discussions. In some cases, Austin has privately been phoning Democrats to oppose it.

The Democratic split on the overhaul is complicating passage of what many Democrats see as one of their few opportunities to enact criminal justice reforms this Congress, especially with bipartisan police reform talks stalled. Powerful groups, such as Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, have thrown their weight behind the bill, but some Democrats with national security backgrounds or large military presences in their districts have not backed it.

With several of his members undecided, House Armed Services Chair Adam Smith (D-Wash.) delayed consideration of the high-profile bill, which was slated for Thursday, according to committee aides.

Smith said Democrats agree that a major shift is needed in the military justice system, but whether changes are only needed for sex crimes or should extend to all felonies is still up for debate. Lawmakers, he said, "weren’t 100 percent clear" on the differences between the competing proposals.

When the Pentagon gave lawmakers a report on military sexual assault and said "’We recommend taking it away for all sex crimes,’ they’re like, ‘Oh yeah, I love that,’" Smith told POLITICO. "And then when someone said, ‘We’re going to take it away for all felonies,’ [they said,] ‘We love that too.’"

Smith said Democrats "didn’t understand" that it was a "binary choice." He wants a clear explanation of the independent review commission’s recommendation versus the proposal to remove military authority over all serious crimes "and then we’ll choose one or the other."

Though he is still undecided on the path forward, Smith said he is "leaning towards" supporting the broader change that removes all serious crimes from the chain of command.

"It’s really complicated, but it is actually the simpler, cleaner approach," he said.

Rep. Andy Kim (D-N.J.), who is among the Democrats still deciding on the serious crimes issue, said he’s seeking answers to certain logistical questions but hasn’t ruled out supporting the broader bill.

“I’m certainly open to that concept but I want to get a sense of what the implementation would be like,” said Kim, who has a large military presence in his district. The New Jersey Democrat added that he wants to know what are the “negative consequences” for taking felonies, in particular, out of that military chain of command.

One idea under consideration is to include both the sexual assault and serious crime provision in the bill, but with a longer timeline for the serious crimes, according to Democrats involved with the discussions. But it’s unclear if that could win enough support.

The dispute raises questions about how the broader measure — championed by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) — can become law. Some Democrats who support both provisions were on the fence because any add on the serious crimes provision could hold up the entire bill, a bipartisan measure named for Vanessa Guillén, the soldier murdered at Fort Hood in April of 2020 after she was sexually harassed by her supervisor.

“I think there was a strong argument for making it a broader bill. There’s also a concern among many fellow Democrats that they don’t want the whole thing to sink,” Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.) said. “It’s most important to pass something than to pass it all at once.”

The most likely path, according to senior Democrats, is including the measure in Congress’s sprawling national defense bill this fall, the National Defense Authorization Act. Still, Speier and Brown are also pushing for a floor vote in the full House, and made their case in a caucus-wide meeting on Wednesday.

“It’s my intention that it gets through intact,” Speier said in an interview.

The proposal would likely be brought up as an amendment when the full Armed Services Committee considers its version of the defense bill in September.

Brown acknowledged that some of his colleagues were still finalizing their decisions, saying some Democrats were “sort of sympathetic to the department’s claim that this is a major change. … What I say is, it was a big change when we desegregated the army in 1948.”

The effort to reform the military justice system has attracted bipartisan support in both chambers. Several House Republicans are cosponsoring Speier and Brown’s bill, including Armed Services members Mike Turner of Ohio and Trent Kelly of Mississippi.

But there’s disagreement over how sweeping Congress should go on an overhaul of the military justice system to combat military sexual assault and other problems plaguing the ranks.

Opinions on how the military should handle sexual assault cases have quickly shifted as lawmakers and even top Pentagon officials became dissatisfied with the military’s inability to stem the tide of sexual assaults.

Austin endorsed removing military commanders’ authority to decide whether to prosecute sex crimes after an independent commission appointed by the Pentagon chief recommended the change. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, also made waves by dropping his longstanding objection to removing prosecution of sexual assault from the chain of command this spring.

But advocates for further reform, led by Gillibrand and others, contend a broader reform is needed. They want to remove commanders’ authority to prosecute all serious crimes that aren’t unique to the military and hand the authority to independent military prosecutors. They point to racial disparities in troops who face courts martial, in addition to sexual assault, as a reason comprehensive reform is essential.

Pentagon brass, however, have warned against more sweeping changes in the military justice system.

The intraparty clash is also playing out publicly in the Senate, where Gillibrand has attempted to force a floor vote on her military justice and sexual assault legislation for months but has been blocked by Senate Armed Services Chair Jack Reed (D-R.I.) and ranking Republican Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma.

Reed has endorsed the limited approach of just changing how the military prosecutes sexual assault cases, aligning himself with Pentagon leadership. He has also sought to keep the debate contained to the Armed Services Committee and its annual defense bill, which is being considered this week. Gillibrand argues the move could result in her proposal being torpedoed in year-end, closed door negotiations on the must-pass bill.

Gillibrand, who chairs the Armed Services panel that deals with military personnel issues, won a bipartisan vote Tuesday in a subcommittee markup to attach her military justice overhaul to the National Defense Authorization Act. But the measure must still survive closed-door full Senate Armed Services Committee deliberations — which kicked off Wednesday morning — where opponents of the measure are likely to try and strip the broader measure from the bill.

“I know we will for sure get something done, whether it’s just sexual assault or more is the question,” Rep. Sara Jacobs (D-Calif.) said.

Heather Caygle contributed to this report.