Throughout Joe Biden’s weeks of infrastructure talks with Sen. Shelley Moore Capito about infrastructure, he was also hearing from another bipartisan broker holding her own quiet talks with Republicans: Sen. Kyrsten Sinema.

The Arizona Democrat has kept the president and his top aides apprised of her own efforts for weeks, according to a source familiar with the conversations. And now that Capito’s talks with Biden are over, it’s time for Sinema’s long-running behind-the-scenes conversations with Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) to take center stage in what’s become Washington’s endless Infrastructure Week.

Except at this point, time is painfully short for the new duo and their larger group of senators to strike a bargain.

“She’s been an honest broker, I’d say that. That’s the greatest compliment around here. She’s kept her word, she’s committed to something,” Portman said in an interview. He acknowledged "differences of opinion," adding: “She would want to spend more … I would want to spend less. We have to find a way to get to the middle.”

The group holed up for hours on Tuesday night after the Capito talks collapsed. Sinema ordered pizza and forced the group to cast their floor votes together before immediately returning to the basement hideaway where they were chatting to keep talks efficient. They had no time to waste.

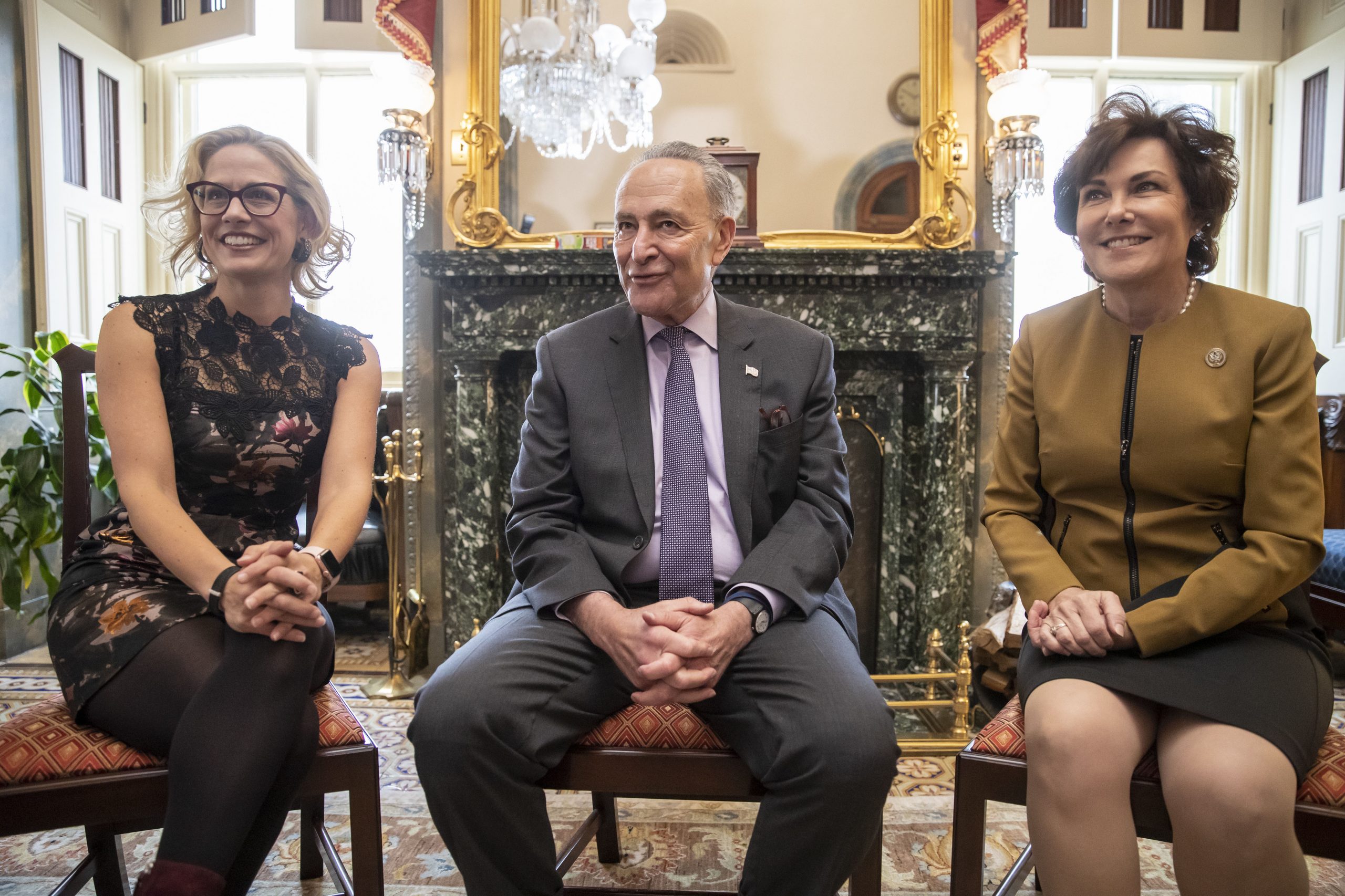

Sinema’s talks are operating on an accelerated timeline, with Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and other Democratic leaders impatient to make progress in the coming weeks before pursuing a unilateral approach that’s been resisted by Sinema and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.). For Biden, the key question is whether he will bend on asking for changes to GOP tax cuts or the overall scope of the bill after yielding nearly $1 trillion to Capito — but still asking for $1 trillion in new spending.

She’s a 44-year-old Senate newcomer, but Sinema has spent her first two-and-a-half years in office forging close relationships with Republicans that rival Manchin’s bipartisan entreaties. And the next few days will test whether that can translate to 60 votes for a big bill that the president will sign.

In a statement for this story, Sinema acknowledged that forging an agreement, with her leadership, between Biden and at least 10 Republicans will be “difficult" but “would help show everyday Americans that we can work together to modernize and make our infrastructure resilient, and expand economic opportunities.”

On Wednesday, deal-seeking Republicans gathered at lunchtime to present their fluid plans for spending several hundred billion dollars above current levels on infrastructure to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. The Kentucky Republican said only that he’s in “listening mode” on Wednesday, a shift from his explicit blessing of Capito’s negotiations with Biden.

Sinema can’t count on Capito’s help at this point. The West Virginia Republican said in an interview she’s stopped attending the bipartisan group of 20-senator meetings she had joined earlier this year and isn’t getting involved in Sinema and Portman’s cohort.

She did offer some advice: Make sure you actually agree on what the definition of infrastructure is and how you would pay for it. Those tips seem basic enough, but disagreement on those terms brought down Capito’s negotiations with Biden before the duo ever got close to a deal.

“I’m really not participating in the other group … I can’t negotiate on two tracks,” Capito said in an interview. “They’re working their own tracks. I wish them luck. Just gotta make sure what the president tells you is what matches the reality of what they really want.”

Sinema has had two telephone conversations on infrastructure with Biden: one Tuesday in the wake of the collapse of the Capito-Biden talks and an in-person meeting in May centered on the issue. She’s also spoken to top White House aides including legislative director Louisa Terrell, Biden counselor Steve Ricchetti and chief of staff Ron Klain recently about the issue. But she purposely didn’t upstage Capito, a close friend and ally, by keeping the talks with Portman low-key and on the back burner.

The Sinema-Portman group is also working with a bipartisan House group called the Problem Solvers Caucus, made up of 58 members divided evenly on party lines who helped the bipartisan Senate group resuscitate Covid relief talks at the end of former President Donald Trump’s administration. Since then, they’ve convened every other week at Manchin’s bipartisan lunch meeting.

When the Problem Solvers Caucus released its version of an infrastructure bill on Wednesday, some of its members privately said it had buy-in from the bipartisan group of deal-seeking senators. As centrists in an increasingly partisan body, many Problem Solvers members already had close ties to Sinema, who previously served in the House.

Sinema also enjoys a better relationship with McConnell than most Democrats, who are deeply skeptical of him and whether he would allow 10 or more of his members to do anything that could boost Biden. McConnell on Wednesday defended Capito and chastised Biden pointedly, claiming he is “unwilling to let go of some of the most radical promises he made to the left wing of his party.”

“McConnell wants Biden to fail,” said Sen.Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio). “There aren’t even 10 Republicans who are even willing to talk to us about compromise. And if we get 10 Republicans you probably lose some Democrats if it’s too squishy, middle-of-the-road minimalist.”

Sen.Susan Collins of Maine, a Republican member of the Sinema-Portman group, said that those trade-offs are a secondary issue. She wants to see more flexibility from the president, who is currently overseas.

“The bigger question is, can the White House accept a more reasonable bill that is focused just on infrastructure and broadband and acceptable pay-fors?” Collins asked.

Still, the distrust of McConnell has Democrats openly pressing to abandon the bipartisan approach — or at least have a party-line back-up plan ready if talks fail. Brown and Schumer are among the Democrats bracing for the deployment of the so-called budget reconciliation process to evade a GOP filibuster and pass a second huge spending bill this year after the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill passed on party lines in March.

The Democrats’ go-it-alone chorus is growing louder by the day, but they will need Sinema and Manchin to join in. Controlling only 50 Senate seats means Biden and his party need total unity if they try and pass a bill without Republicans.

Now that Manchin and Sinema are knee-deep in arbitrating infrastructure talks with Biden and Senate Republicans, the pair will soon have an answer on whether their bipartisan aspirations harmonize with the president’s vision of spending trillions on clean energy, roads and bridges and paid family leave.

“It’s a good test. Because this is not deep policy. It’s not particularly partisan,” said Sen. Angus King (I-Maine). “If we can’t make it on this, it’s a bad sign.”

Still, Democrats have made it clear they have essentially zero patience left after the Capito talks with Biden dragged out for about six weeks. Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), a member of the larger bipartisan group, said he expected it to meet on Thursday again.

His hope was that by the time senators headed to their home states Thursday afternoon, they would know whether a bipartisan agreement would materialize: “If we don’t get a deal pretty damn quick, we ain’t gonna have a deal.”

Sarah Ferris contributed to this report.