An amnesty on historical prosecutions in Northern Ireland will apply to former soldiers and to terrorists, under plans expected to be announced in tomorrow’s Queen’s Speech.

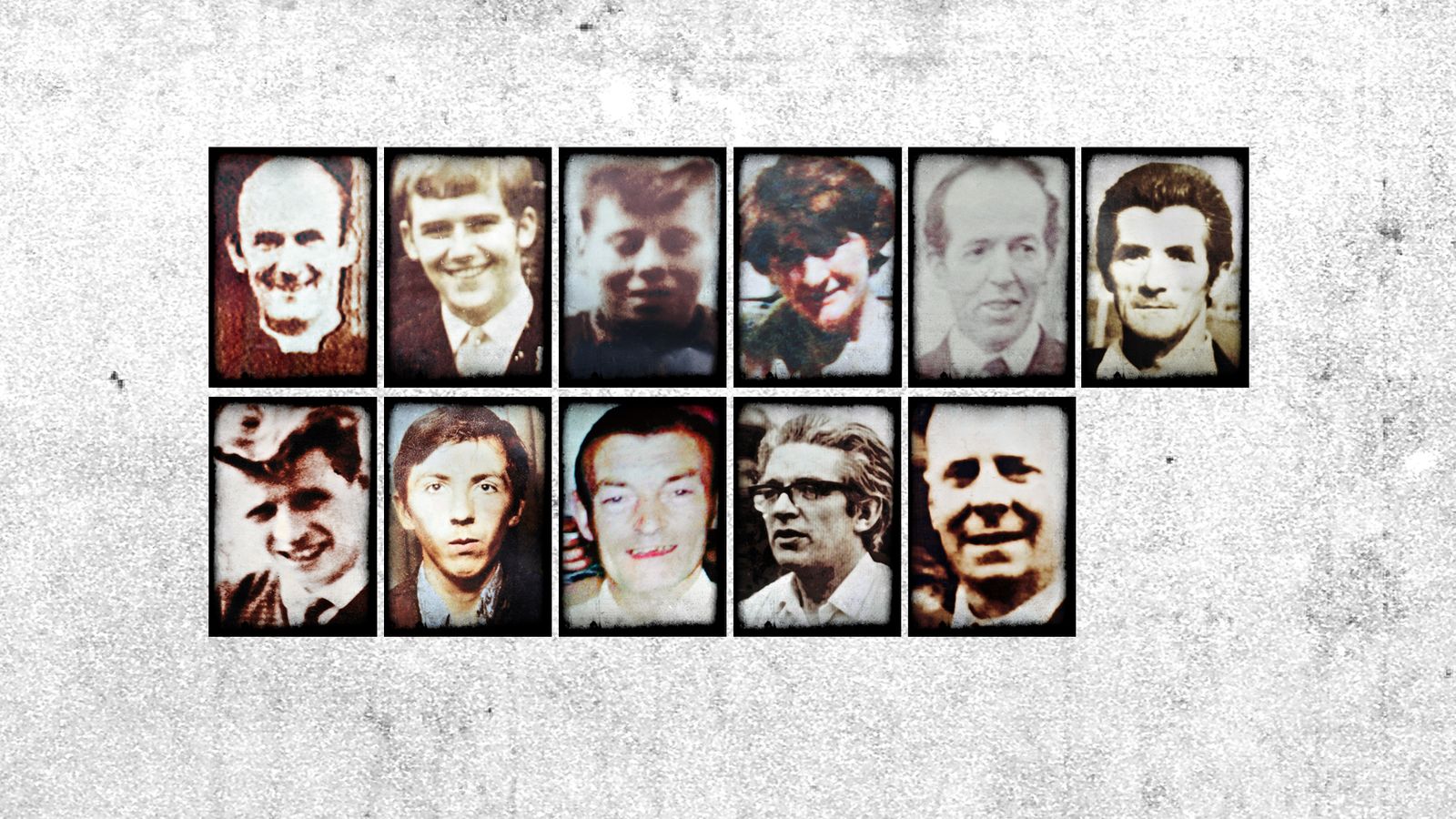

On the same day, a coroner will publish her findings into the deaths of 10 civilians shot dead during military operations at Ballymurphy in 1971.

The proposed statute of limitations on offences committed before the 1998 Good Friday Agreement is bitterly disappointing for relatives of the Ballymurphy victims.

The dead included a Roman Catholic priest who had just given another victim the last rites, two teenagers and a mother of eight children.

The inquest, which lasted 16 months, heard from more than 100 witnesses, including 60 former British soldiers and 30 civilians.

In August 1971, Northern Ireland was in turmoil – a decision to detain IRA suspects without trial fuelling serious disorder.

There were reports of a gun battle between paratroopers and terrorists at Ballymurphy in west Belfast but none of the victims was armed.

Five months later, the same battalion of the Parachute Regiment shot 14 people dead in Londonderry, the day that became known as Bloody Sunday.

Briege Voyle, whose mother Joan Connolly was one of the Ballymurphy victims, said her last words were: “The Army wouldn’t shoot you.”

“They could see very easily that she was a woman and… the first shot was aimed at her face. To me, that’s personal,” she added.

John Taggart’s father Daniel, who was shot 14 times, was one of four people killed on the same small patch of ground.

Struggling to contain his emotion, he recalled having to listen to the evidence: “It was really hard for us to sit through that, really hard.”

The issue of Northern Ireland’s troubled past still dominates its present – some victims would settle for the truth but others continue to demand justice.

Author Brian Rowan, who has written extensively on legacy, says one senior police officer likens it to a “mass grave” that Northern Ireland keeps falling into.

He said: “I think the only way out of this is an amnesty. It’s the word we will not speak, it’s too poisonous.

“But if we don’t go there, then we aren’t going to have a legacy process and with the wars over, we’re going to spend the next 30 years fighting the peace,” he added.