If invading Ukraine was the greatest political mistake of President Vladimir Putin’s 24 years in power, then partial mobilisation that September – at least domestically – was perhaps the second.

Russian society experienced a moment of collective shock, stunned into acknowledging this war might affect them too.

There were protests, a mass exodus, spasms in the opinion polls.

But they were quick to subside once the numbers were reached and the immediate fear of being press-ganged into the armed forces on your morning commute faded.

The Kremlin may not accept the first of those mistakes, but it does recognise the second.

So if there is one certainty before the presidential elections next March, beyond the fact Mr Putin will run and win, it’s there will be no further mobilisation before that inevitable and resounding victory.

In the meantime, the Kremlin spin doctors are hard at work.

The message is simple: Russia is great, the future is rosy. And don’t worry about the war, it’s in hand.

A utopian vision of Mother Russia

The public seem to lap this up.

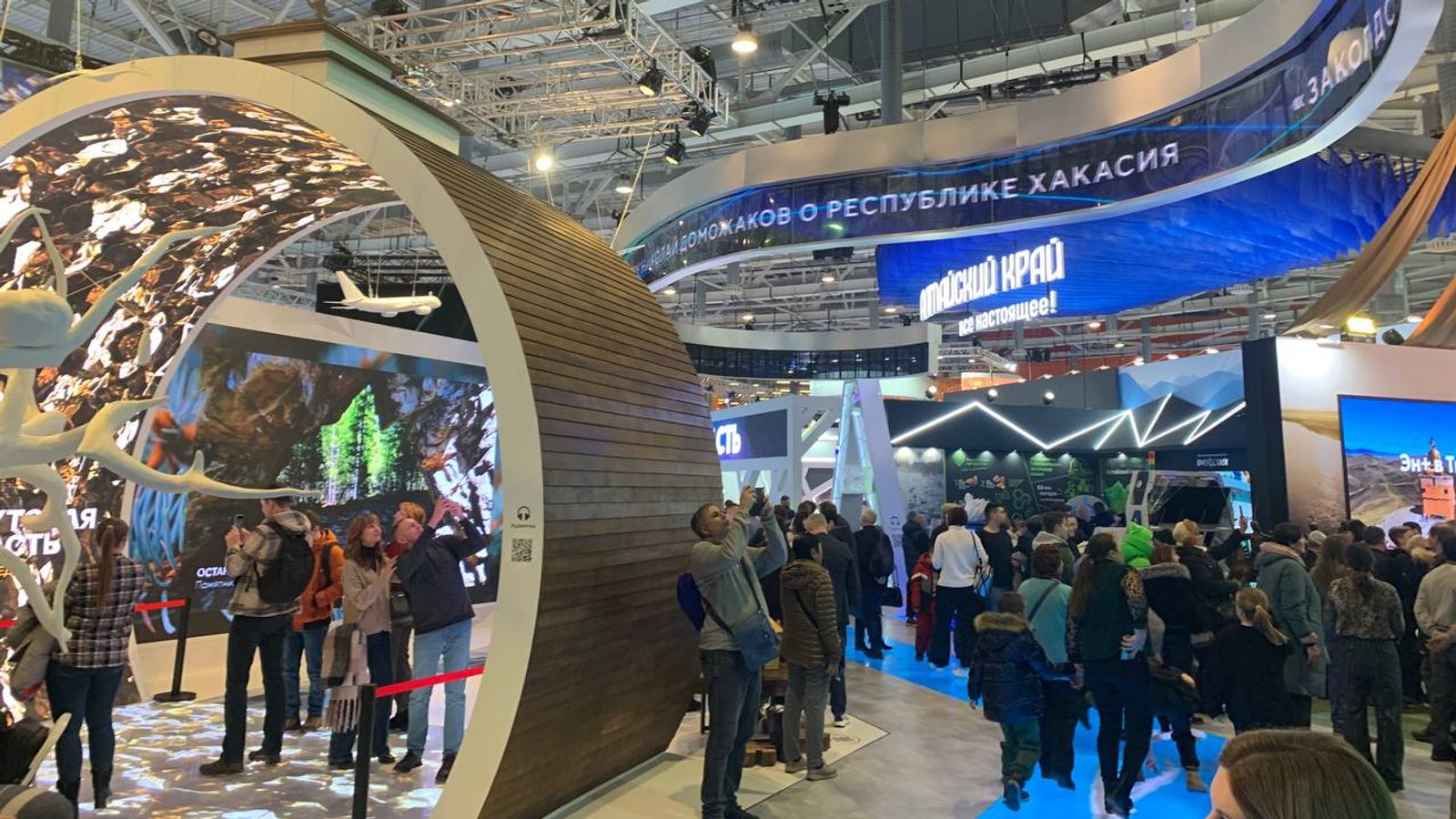

Just take the new exhibition called simply Russia, running at the huge Soviet “All-Russian exhibition centre” in Moscow until April, just after the elections.

When we visited on a Tuesday afternoon, it was rammed.

Children with the Russian tricolour painted in hearts on their cheeks marvelled at huge LED screens showing the breadth and diversity of Mother Russia, and clambered around interactive displays.

A statue of a god of the huge Yenisey river towered over glittering futuristic cities, apparently due to be built somewhere along its banks.

Mannequins modelling Russian high fashion stood a few feet from photos of Mr Putin on horseback in the wilds of the remote region of Tuva.

It was a day focusing on Tuva when we were there, and a Tuvan wedding ceremony was taking place in the central exhibition space to a rapturous audience.

You would be forgiven for forgetting that this glittering LED nation of the future is also a country at war and under sanctions.

But the people aren’t meant to think about that, or the fact the technology and the microchips and the IT specialists might not be there to create this high-tech paradise.

This was all about Russian greatness and being proud of the motherland. Think about that, and everything else can fade away.

Read more:

Russian forces raid gay clubs

Zelenskyy signals ‘new phase of war’

How Kremlin propaganda seeps through

In a less well-attended corner of the exhibition were four stands which per international law should not have been there: the four Ukrainian regions illegally annexed by Russia last year.

Sergei, himself from Kherson and manning the Kherson stand, sullenly regurgitated the Kremlin’s lines on Nazis and Volodymyr Zelenskyy being a supposed puppet of the West.

The fact Russia retreated from the city of Kherson and is still fighting over the region didn’t bother him.

“Sometimes it controls it, sometimes it doesn’t,” he said.

At the Donetsk stand, a mother and her daughter raved about the exhibition but became a little forlorn when the topic turned to war.

“The situation is very difficult, but we hope and believe that there will be peace on our land,” she said.

One of the stand’s organisers interrupted as we were speaking. She wanted to know if our interviewees had formulated Donbas as Ukrainian territories, which they had not.

“Is that what they asked you?” she continues, gesturing to us. They shook their heads and she left.

“We don’t want to get into trouble,” the mother sighed.

Spiting the world

Kremlin spin is not a blunt instrument. It is not just what you’ll see on state TV.

It infects the consciousness of the nation through myriad different ways, via schools, shows, social media, billboards, fear.

It is sophisticated, it is convincing, it uses Russian talent and skills and creativity to further the Kremlin’s purpose.

Take the pop star Yaroslav Dronov who goes by the stage name Shaman.

Before the war, he was not particularly well known. But his single Vstanem, Rise up – released the day before Russia’s invasion for Defender of the Fatherland day – became a sensation, given subsequent events.

Another hit is Ya Russkiy, I’m Russian, apparently “to spite the world” so the lyrics go, and it is so ubiquitous it is almost an unofficial anthem. On stage recently he mock-detonated an atomic bomb during a performance of that song.

We caught up with him at a patriotic play in Moscow and asked him what he meant by his lyrics.

“To be Russian is to be in one’s place and do work giving your all,” he replied.

When I asked if he felt he was more an artist or a propagandist his agent intervened and told us we were the propagandists.

But Shaman is one of the hit acts at the patriotic set-piece concerts which Mr Putin attends, and he’s sure to feature as the campaign hots up.

Making ‘Putinism’ cool

He makes patriotism – and Putinism – cool and catchy.

He is useful for the Kremlin and the Kremlin’s razor-sharp focus on patriotism has proven useful for his career too.

The play we saw him in told the story of three Russian women working on the frontlines in Donbas, and it was filled with the loss and the tragedy which both sides experience in war.

The audience were moved, some had tears in their eyes, some waved Russian flags. The actresses had been to Donbas themselves and had written the songs based on their impressions.

“There is this awareness that this is our reality,” one of them said. “The only thing we can do is help, from all our hearts, help with a pure heart and firmly believe that soon everything will be fine, for every person in our big great country.”

The patriotic narrative is everywhere and it is compelling.

Russians are told they had no choice but to send in the troops, and “seek justice” for Donbas as Mr Putin has put it.

It is easier for them to believe it than to face up to uncomfortable truths. That by invading Ukraine, Mr Putin has set their country back. And that the Kremlin’s glittering projection of the future might look very different to the one they end up living.