Human cells have been grown in monkey embryos by scientists in the US, sparking ethical concerns and warnings that it “opens a Pandora’s box”.

Those behind the research say their work could help tackle the severe shortage of transplant organs as well as enable better overall understanding of human health, from the development of disease to ageing.

But some experts in the UK have highlighted the significant ethical and legal challenges posed by the creation of such hybrid organisms and called for a public debate.

Concerns have been raised after researchers from the Salk Institute in California produced what is known as monkey-human chimeras.

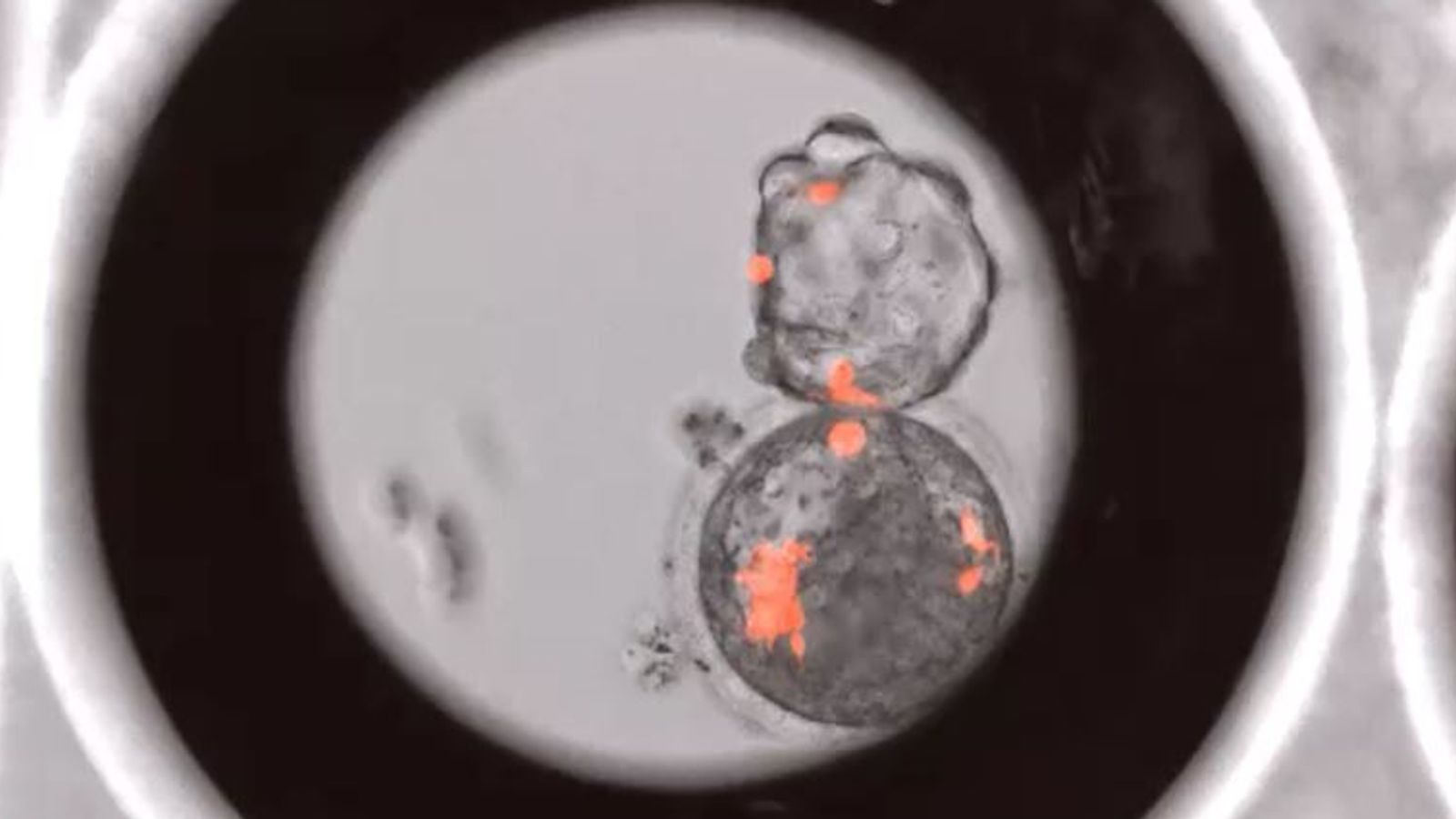

This involved human stem cells – special cells that have the ability to develop into many different cell types – being inserted in macaque embryos in petri dishes in the lab.

The aim is to understand more about how cells develop and communicate with each other.

Chimeras are organisms whose cells come from two or more individuals.

In humans, chimerism can naturally occur following organ transplants, where cells from the organ start growing in other parts of the body.

Professor Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, who is leading the research, said: “These chimeric approaches could be really very useful for advancing biomedical research not just at the very earliest stage of life, but also the latest stage of life.”

In 2017, he and his team created the first human-pig hybrid, where they introduced human cells into early-stage pig tissue but found the environment provided poor molecular communication.

As a result, the researchers decided to investigate lab-grown chimeras using a more closely related species.

The human-monkey chimeric embryos were monitored in the lab for 19 days before being destroyed.

According to the scientists, the results, published in the journal Cell, showed human stem cells “survived and integrated with better relative efficiency than in the previous experiments in pig tissue”.

The team said understanding more about how cells of different species communicate with each other could provide an “unprecedented glimpse into the earliest stages of human development” as well as offer scientists a “powerful tool” for research on regenerative medicine.

Insisting that their research has met current ethical and legal guidelines, Prof Izpisua Belmonte said: “As important for health and research as we think these results are, the way we conducted this work, with utmost attention to ethical considerations and by coordinating closely with regulatory agencies, is equally important.

“Ultimately, we conduct these studies to understand and improve human health.”

Responding to the research, Dr Anna Smajdor, lecturer and researcher in biomedical ethics at the University of East Anglia’s Norwich Medical School, said: “This breakthrough reinforces an increasingly inescapable fact: biological categories are not fixed – they are fluid.

“This poses significant ethical and legal challenges.”

She added: “The scientists behind this research state that these chimeric embryos offer new opportunities, because ‘we are unable to conduct certain types of experiments in humans’.

“But whether these embryos are human or not is open to question.”

Prof Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities, University of Oxford, said: “This research opens Pandora’s box to human-nonhuman chimeras.

“These embryos were destroyed at 20 days of development but it is only a matter of time before human-nonhuman chimeras are successfully developed, perhaps as a source of organs for humans. That is one of the long-term goals of this research.

“The key ethical question is: what is the moral status of these novel creatures? Before any experiments are performed on live-born chimeras, or their organs extracted, it is essential that their mental capacities and lives are properly assessed.”