Blue whales have always been considered record breakers when it comes to the size department.

Not only is it the largest animal alive today, but the species is often considered the heaviest to have ever lived.

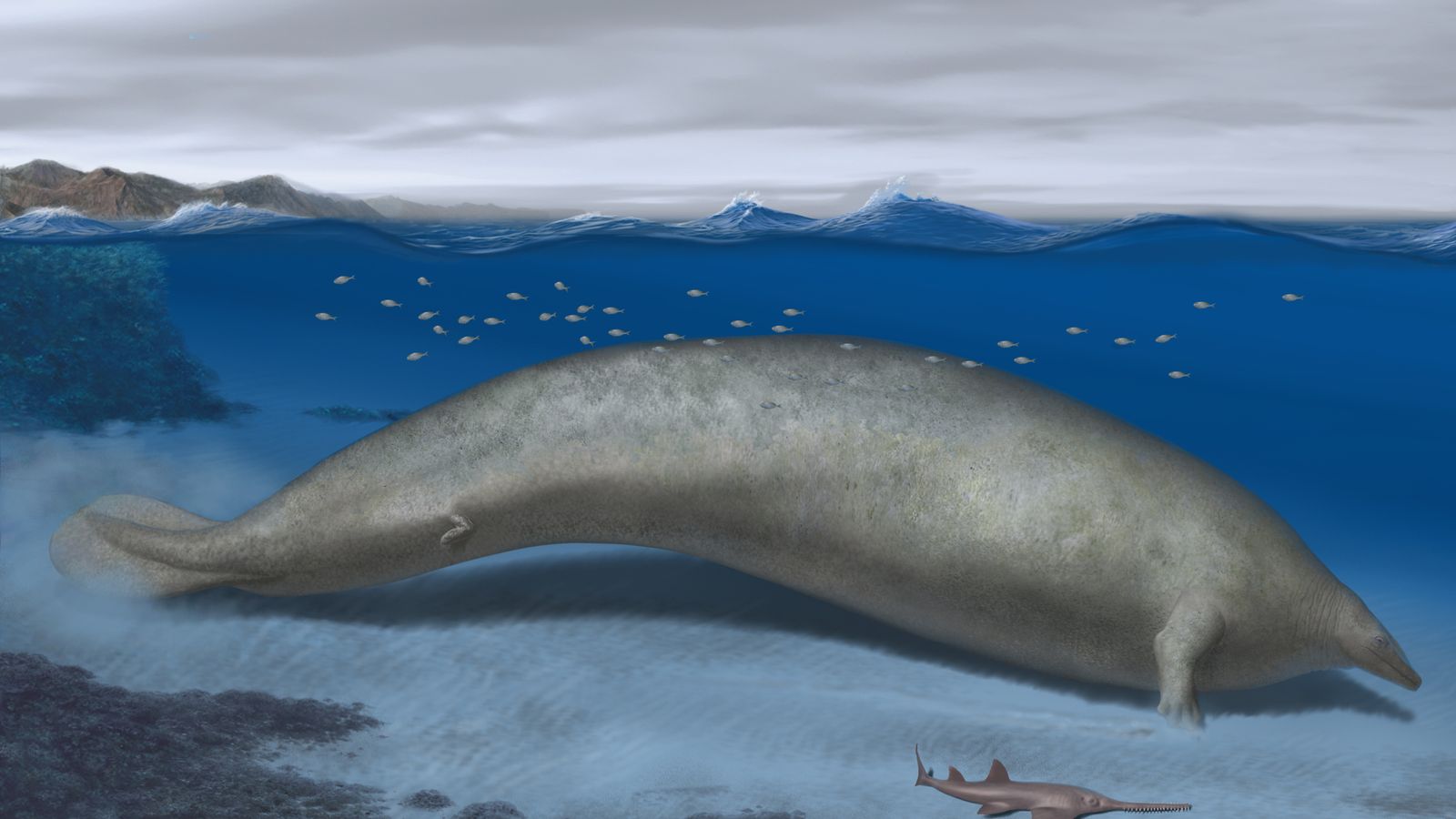

But new research shows that title might belong to an ancient whale species which swam in the oceans around 39 million years ago.

Researchers have analysed the remains of a partial skeleton uncovered 13 years ago in the Ica desert on the southern coast of Peru.

Their findings, published in the journal Nature, suggest this extinct species had a body mass of up to 340 tonnes – three times heavier than the blue whale.

Scientists have named the species Perucetus colossus, a nod to its huge body mass and the place where it was discovered.

“It might be the heaviest animal known to date,” said Dr Eli Amson, a researcher at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in Germany.

Warning over invasive salmon species set to arrive in UK waters

Deepest fish ever recorded revealed by scientists

France ordered to ban fishing in Bay of Biscay as dolphins are in ‘serious danger of extinction’

“In any case, it was at least as heavy as the blue whale. But the P. colossus we describe was not longer than the largest blue whales.

“We estimate the new species’ specimen to have been 17m-20m (56ft-66ft) long, while blue whales can reach 30m (98ft).”

The ancient species belongs to a family of extinct cetaceans, a class of mammals that includes dolphins, whales and porpoises, known as basilosaurids.

They lived from the middle Eocene to the late Oligocene epoch, about 41 million to 23 million years ago.

A reconstruction of the P. colossus suggests it is two to three times heavier than the 25m (82ft) long blue whale skeleton on show at the Natural History Museum in London.

Read more:

20,000 visitors a day seeing ‘fake bear’ after zoo video goes viral

Mysterious object found on Australian beach identified

Be the first to get Breaking News

Install the Sky News app for free

Researchers say the tremendous bone mass of P. colossus is caused by extra bone on the outer surface of the skeletal elements and the filling of inner cavities with compact bone.

This extra weight helps these animals regulate their buoyancy and trim underwater, the authors said.

The researchers speculate that P. colossus may have been a slow swimmer and lived near the coast.