Six men have been found guilty of murder over the 2016 Brussels terror attacks that left 32 people dead.

The trial lasted seven months and was held in the former headquarters of NATO.

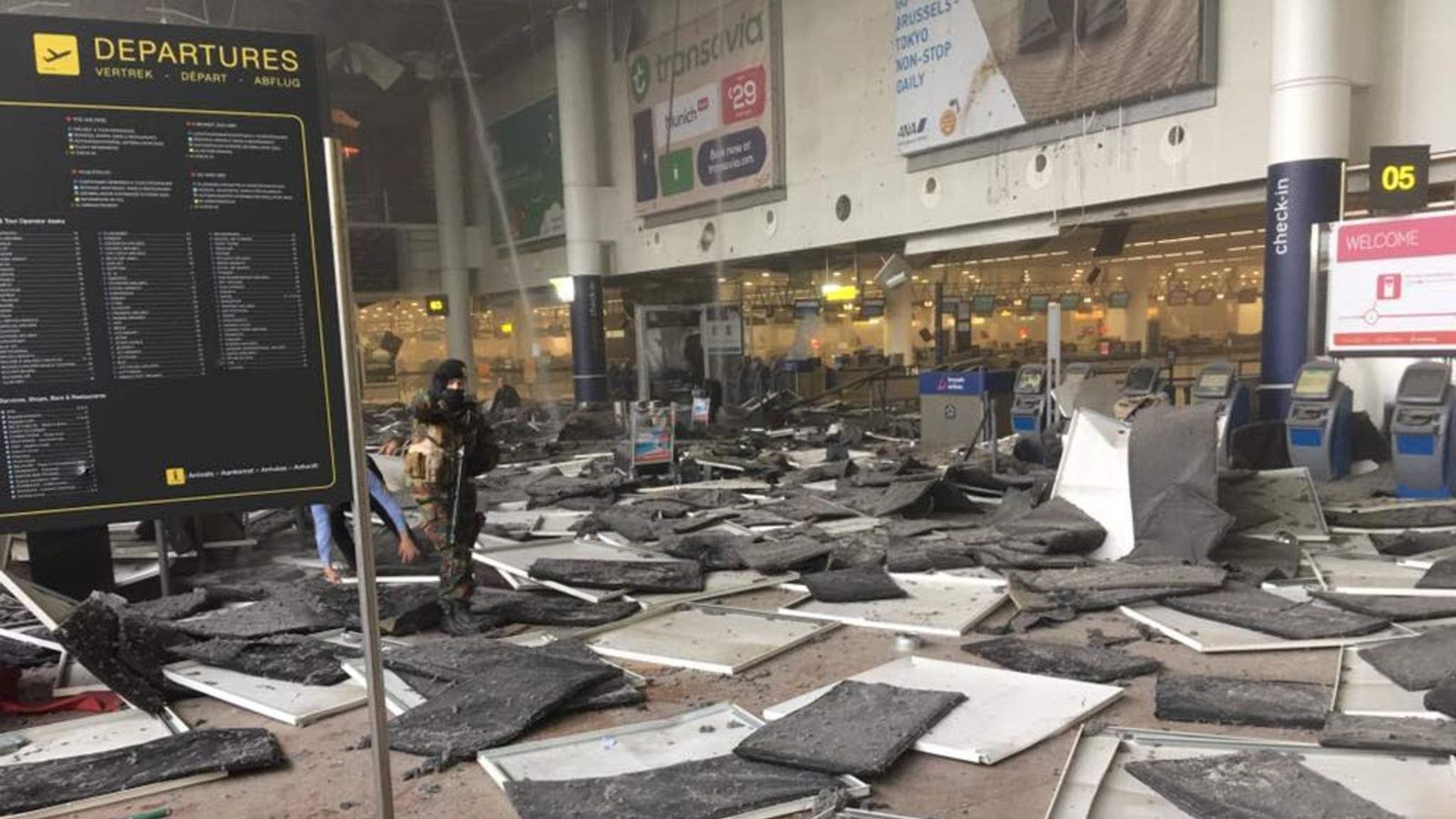

Bombs exploded at Brussels Airport in March 2016 and then on a metro train passing through the city’s European quarter, in attacks claimed by Islamic State.

Fifteen men and 17 women were killed, with more than 300 people injured. The attacks were the deadliest in Belgium since the end of the Second World War.

Among those convicted were Salah Abdeslam, the main suspect in the Paris attacks in 2015, which killed 130 people.

Abdeslam, who was born and brought up in Brussels, has already been convicted, at a trial in France, for his part in those attacks.

The French sentenced him to life imprisonment, without parole, but allowed Abdeslam, along with four others, to be transported to Belgium so they could face justice once more.

One of the group is presumed to have been killed in Syria and was tried in their absence.

Read more:

How the Brussels attacks unfolded

The trial in Belgium is estimated to have cost at least €35m (£30.2m).

Nearly 1,000 people were represented during the hearings, underscoring how many lives were impacted by the attacks – but now the country has some form of closure.

The immediate aftermath led to vigils, protests, border checks, parliamentary inquiries and even the partial evacuation of the nation’s nuclear power stations.

Belgium was a country gripped by a fear that took a long time to quell. Now, it knows where to place the blame.

‘The man in the hat’

Also found guilty was Mohamed Abrini, who became known as “the man in the hat” after being seen in a CCTV image taken at Brussels Airport shortly before bombs were blown up.

Abdeslam was arrested during a police raid and shoot-out in Brussels in March 2016.

The arrest prompted the terrorist group to change its plans – instead of returning to Paris to launch a new wave of terror attacks, as planned, they rushed into place to cause devastation in the Belgian capital.

The murders began at the airport.

CCTV footage shows three men pushing trolleys through the departure terminal shortly before the explosions. In all of their bags there was a bomb, but only two of them were detonated by suicide attackers.

The third man was Abrini. A friend of Abdeslam since childhood, he survived the attack after failing to detonate his device.

He, too, had previously been convicted by the court in France for his involvement in the November 2015 attacks.

Abrini told the Brussels court that “just like in Paris, they’ll convict us for what others did” and said that he, and the other defendants, “are not the tip of the pyramid”.

He added: “You never caught those pulling the strings but you have to trot out someone and that someone is us.”

‘Bomber pulled out when he saw women and kids’

Abrini also claimed that he had suffered a change of heart and refused to blow up his bomb after being shown his target – a queue of passengers preparing to fly to America.

“I saw women and children. I turned around immediately and told them ‘I’m not doing that’,” he claimed.

The court asked him why, if he had suffered a sudden pang of conscience, he did not try to dissuade the other bombers or defuse the devices, but received no clear answer.

Instead, Abrini maintained that those killed and injured in the attack were, in fact, victims of both Islamic State and the foreign policy of Western nations.

The airport was evacuated amid scenes of chaos and fear. But just an hour and a quarter after the airport explosions, another device was detonated in the middle carriage of a train at Maalbeek metro station, not far from the headquarters of the European Commission.

As well as the 32 people who were killed by the attacks, three terrorists also died.

More than 300 people were injured, 62 of them critically.

Woman euthanised over attack trauma

In 2022, a young Belgian woman, who had been in the airport at the time of the attack, decided to be euthanised because of the “intolerable psychological” strain it had placed on her life.

The trial in Belgium had been delayed because of questions about where such a high-profile, maximum-security event could be held.

In the end, millions of euros were spent converting NATO’s former headquarters building into a courtroom.

Police protection was high and overt.

Abdeslam, who denied any involvement in planning the attacks, told the court that he had “always tried to do good”.

When asked if he had any faults, he said: “I don’t know of any.”

He said that Islamic State attacks on Europe had been a response to bombing raids carried out by Western nations on Raqqa and Mosul, a claim repeated by a succession of defendants.

Complaints from defendants of humiliating strip searches caused more delays, with court sessions frequently interrupted and postponed.

‘You are at a crossroads’

The court heard moving testimony from many people profoundly affected by the attacks.

The mother of Bart Migom, a 21-year-old who was on his way to America to see his girlfriend, told the defendants: “You are at a crossroads. You can choose to do as you have done so far, or you can look yourselves in the face and take responsibility for all of this. I hope you do that.”

Another person, Caroline Leruth, told the court she had survived only because Abrini had not detonated his bomb. “I am standing here today because of your cowardice,” she said.

However, the statements from victims also included criticism of the response from Belgian authorities, alleging that help had taken too long to arrive and that they had been treated unsympathetically after the attacks, with health insurance companies trying to minimise their injuries.

Nine people were placed on trial, although the prosecution, in an unusual move, later asked for one of the men, Ibrahim Farisi, to be acquitted after accepting that there was not enough evidence against him.

A tenth, Oussama Atar, was convicted in his absence, although it is believed that he is dead after previously going to Syria to join Islamic State.