Joe Biden’s campaign promise to work with the GOP is crashing into his political reality: It’s easier to just go around the Republican Party and pass his agenda with Democratic votes.

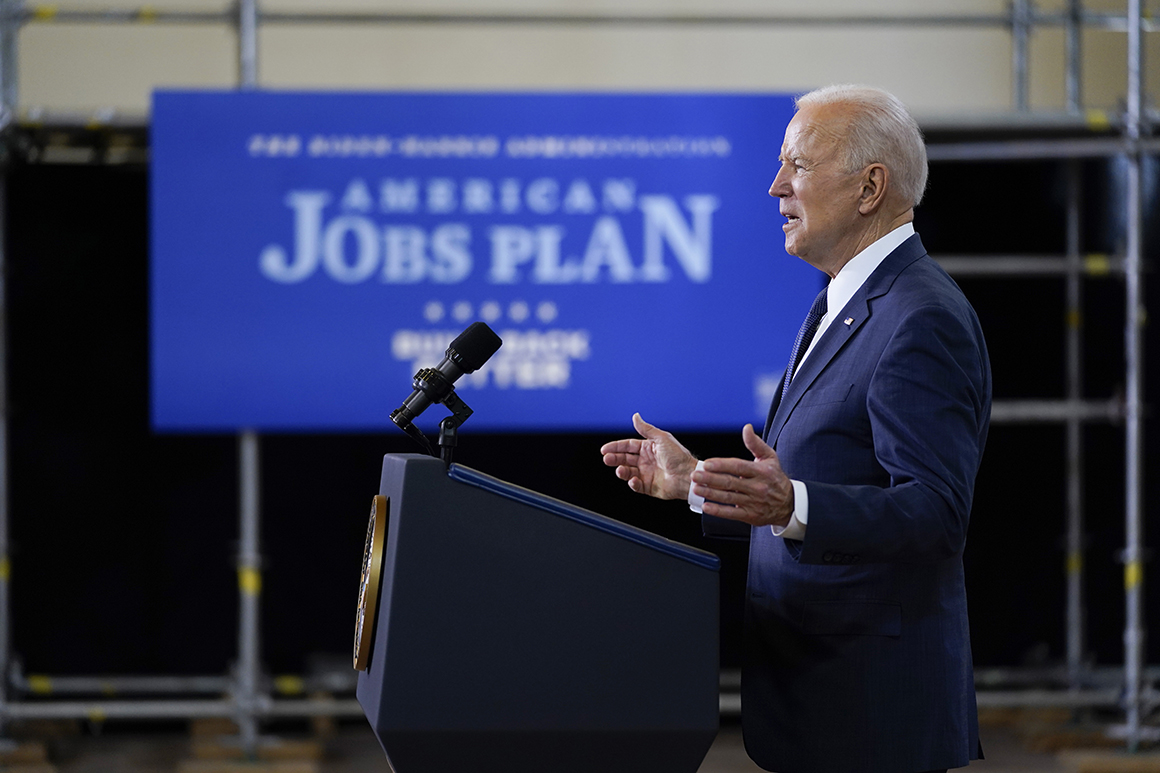

As Biden presses a fresh multitrillion-dollar proposal to spend new tax revenue on manufacturing, infrastructure and health care, the president and his party are poised once again to completely sidestep Senate Republicans whom Biden long argued he could work with. Sure, his White House says it would prefer to work with the GOP — but more importantly, Biden has indicated he’s not going to let the Republican Party stand in his way.

Sound familiar? That’s precisely how the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill played out just a few months ago. Both bills began with Biden suggesting a spending target and policy changes that Republicans simply won’t touch. But the Republicans whom the president has said he wants to work with are holding out hope that somehow this ends differently, with him making more effort to meet them halfway.

“I believe that President Biden does want a bipartisan approach,” said Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), who has spoken to Biden regularly since the 2020 election. “I have no reason to believe that he has changed. But I think that there is a lot of pressure on him from his staff and from outside leftist groups. And I would urge him to remember his past successes in negotiating bipartisan bills.”

Biden’s administration gave a briefing on his new plan to centrist Republicans, though they worry that may just all be for show. That’s because Senate Democrats are preparing to pass yet another massive spending bill with a simple majority and Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote, using the blunt filibuster-proof tool known as budget reconciliation that would require zero GOP buy-in.

Collins said she has spoken one-on-one recently with Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge, describing the administration’s overall outreach as “significant.” But she said that for Republicans, “the question is: is the administration so wedded to the details of its plan, including its exorbitant top line, that these are just courtesy briefings as opposed to the beginning of a true dialogue?"

What happens in the next few weeks to Biden’s $2 trillion-plus spending plan could determine the course of his first two years in office. If he takes a partisan approach again to enact tax increases and new spending, it would almost certainly chill the already difficult gun safety and immigration reform talks taking place in a closely divided Congress.

Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), a member of a dealmaking group of 20 senators, said that infrastructure is second only to pandemic relief in terms of its potential for bipartisanship.

“If we can’t do it in these areas, I don’t know where we can do it,” Portman said. As for future negotiations, he observed: "You lose the muscle memory of working together if you’re constantly jamming through partisan measures. And it doesn’t have to be this way."

But it is the most efficient way for Biden to pass as much of Democrats’ agenda as he can before the midterms freeze legislative ambitions, since several Senate Democrats are balking at scrapping the chamber’s 60-vote threshold to pass most bills. Using the restrictive, party-line path of budget reconciliation averts the need for negotiations with Republicans that would immediately drive the price tag for Democrats’ proposal down by hundreds of billions of dollars and lead to major policy concessions.

Even though Biden can approve more than $4 trillion in new spending while raising taxes on the wealthy and corporations, all with only 50 votes in the Senate and a narrow majority in the House, the White House maintains the best path forward is a bipartisan one.

"The president and his administration are eager to work across the aisle, in good faith, to deliver these historic investments," said Andrew Bates, a White House spokesperson. "That’s why he has already met with Republican senators himself regarding infrastructure, and why Cabinet members and White House senior staff have been frequently engaging with Republican members on this plan since before it was even announced, actively seeking their ideas.”

White House officials engaged Hill Republicans for weeks on the infrastructure pitch, starting before its official rollout. That included a teleconference last week with Biden economic advisers and 31 Republicans, according to the White House. Biden aides say that type of sustained discussion underscores that their outreach is no fig leaf.

Even before his victory, Biden’s campaign believed that Republicans would be eager to return to legislating after four years of President Donald Trump’s erratic style. But Democrats shocked the political world by taking control of the Senate in January, making bipartisanship a “maybe” instead of a “must” for key economic agenda items.

The president last year leaned on his longtime relationship with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell to market himself as a Democrat able to chip away at GOP obstructionism. But since Biden’s term began, McConnell has made clear his warmth toward the president goes only so far.

“I like him personally. We’ve been friends for a long time. He’s a first-rate person,” McConnell said in Kentucky on Thursday. “Nevertheless, this is a bold, left-wing administration. I don’t think they have a mandate to do what they’re doing.”

The GOP leader then vowed that none of his 50-member Republican conference would support Biden’s new spending bill, though Collins said in the Senate there’s “widespread bipartisan support for a focused package.” The GOP took a similar position on coronavirus relief and offered about one-third the amount of spending that Biden had proposed, an entreaty that Democrats immediately ignored.

“I am surprised and disappointed that they didn’t seek any input from Republicans,” Portman said. “I continue to be hopeful that President Biden’s message in the primary and the general election and the inaugural stage will be carried out. But I haven’t seen it yet.”

Biden has attempted to conduct outreach in other ways, hosting Republican governors in the Oval Office in addition to meeting with the congressional GOP. But even as White House staff try to keep cross-aisle communication going, they put their confidence in polling that shows Americans care more about getting things done than doing them on a bipartisan basis.

It’s also not clear how much time Democrats are going to spend on GOP input this time around before going down the path of reconciliation. While they won’t move as quickly as they did on coronavirus relief, Speaker Nancy Pelosi has privately said she is aiming for House passage of Biden’s latest plan by July 4.

The White House is releasing the infrastructure package in two parts, which Democrats say is an attempt to gauge Republican support for elements more focused on physical infrastructure versus health care. White House officials and Democratic lawmakers argue that infrastructure is bipartisan and has support from Republican mayors and governors, even if GOP members of Congress aren’t backing the Biden plan.

But there’s no greater signal that Democrats don’t necessarily need Republicans to come on board than Biden’s idea to pay for his infrastructure spending. He’d do so by partly undoing the GOP’s signature Trump-era legislation: the 2017 tax cut bill.

Natasha Korecki contributed to this report.