The crash in shares of Deliveroo this morning is an event with massive implications for both investors and for future investment.

This was the biggest flotation on the London Stock Exchange since the IPO of Glencore, the mining and commodity trading firm, in May 2011.

There are an eerie number of similarities between the two flotations.

As with Deliveroo, Glencore was dogged by controversy in the build-up to the IPO, particularly in environmental, social and governance matters.

While Deliveroo’s treatment of its couriers and its employment practices have come under the microscope, Glencore was haunted by accusations of causing pollution in Zambia, damaging crops and the health of schoolchildren.

As with Deliveroo, City institutions also objected to the valuation being sought by Glencore, arguing the company was an unknown quantity whose prospects were hard to value.

And, as with Deliveroo, shares of Glencore ended up being priced ‘to go’ in the flotation – being sold towards the bottom of the price range circulated by its bankers ahead of the IPO.

The food delivery company will be hoping desperately that that is where the similarities end.

Glencore’s shares have never since traded at the 530p level at which they were sold to investors. Deliveroo will be hoping the only way from here is up.

One key difference is that, in the case of Glencore, a lot of investors – chiefly those running funds replicating the performance of an index such as the FTSE 100 – had no choice but to invest because the company had been put on a process fast-tracking its application to join the Footsie.

In the case of Deliveroo, that was not possible, because of the unusual dual-class share structure that will be in place for the first three years.

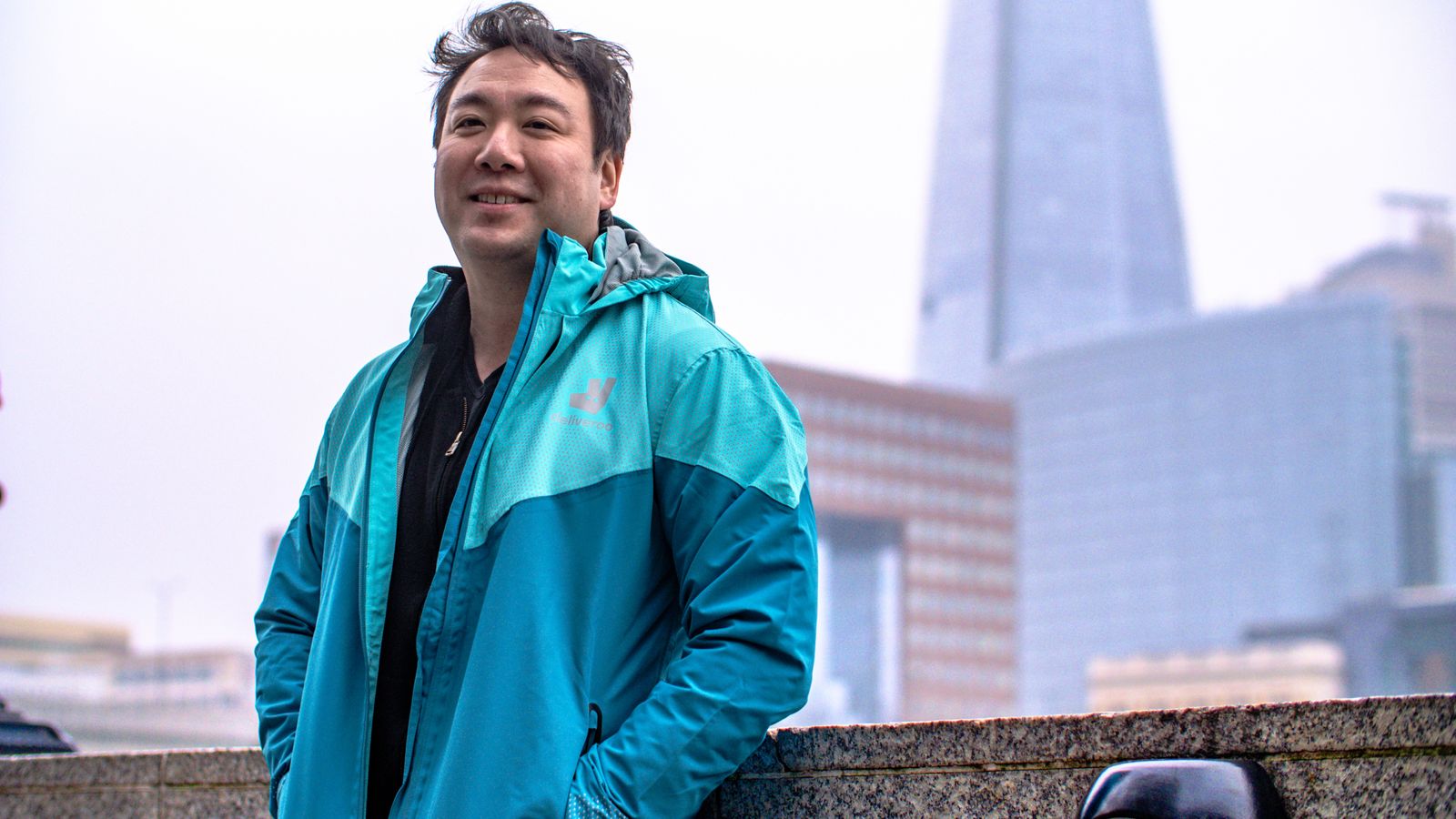

This arrangement gives the holders of a certain class of share more voting rights than the holders of another class of share. The aim was to enshrine the power of Will Shu, the founder, who after the IPO owns 6.3% of the company but 57.5% of the voting rights.

Such arrangements are not unusual in the United States, having been used by the likes of Facebook and Alphabet, the owner of Google.

In this country, however, companies with dual-class share structures are not eligible for the FTSE 100.

Accordingly, a host of blue-chip investors – among them Aberdeen Standard, Aviva Investors, Legal & General Investment Management, M&G, Janus Henderson, Jupiter, BMO Global Asset Management and CCLA – chose not to invest in Deliveroo.

These fund managers, who also expressed concerns about workers’ rights at the company, felt the dual-class share structure could act against the interests of minority shareholders.

This boycott by some institutional investors was their way of blowing a raspberry at the recent government-backed review of the UK’s listing rules by Lord Hill, the UK’s former European Commissioner, which recommended allowing companies with a dual-class share structure to be accorded ‘premium listing’ status on the London Stock Exchange.

Lord Hill argued this would encourage fast-growing companies, particularly in the tech space, to look at floating in London rather than New York. A host of exciting UK companies have recently alighted on the latter, among them the biotech company Immunocore and Farfetch, the luxury fashion retail platform. The latest to opt for New York’s rather more relaxed rules is Cazoo, the online used car retailer.

Lord Hill’s recommendations were eagerly endorsed by Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, who even went so far as to put his name on the press release announcing the flotation in which he called it a “true British success story”.

The dreadful start that Deliveroo has made to life as a quoted company means that fewer fast-growing companies are now likely to look at listing in London. It is a major setback to Mr Sunak’s ambition of attracting more of them to the UK market.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Questions are already being asked of Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, the investment banking giants that brought the company to market.

Most IPOs usually seek to leave something on the table for the next man – taking care to ensure that the issue is conservatively priced and enabling the shares to enjoy a ‘first day pop’ when trading begins. The banks will argue, legitimately, that they priced Deliveroo shares at the bottom of the pre-IPO range published.

They can also argue that, with so many big names in the London investment community shunning the issue, they were forced to cast the net further for would-be investors. The chances are that, in the absence of so many institutional investors, many of those on the IPO order book will have been hedge funds looking to ‘flip’ the shares for a quick gain.

Some of those funds, having seen the way the shares opened trading at 8am today, may have decided to cut their losses and sell there and then.

It is fair to say that Deliveroo suffered from a certain amount of bad luck.

Its cause was not helped by the Supreme Court ruling, during the IPO process, that Uber drivers were classed as workers rather than contractors. That raised difficult questions about the legal status of Deliveroo couriers and the impact on the company’s path to profitability in future were it forced to accord them worker status.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

Against that, it has to be said that Deliveroo’s PR campaign ahead of the IPO was lacklustre, to say the least.

There was a lazy assumption, for example, that a soundbite from the chancellor would be enough to overcome the very real concerns among investors about the share structure.

There was little attempt to push back against concerns expressed about the lack of profits at the company, even when they came from James Anderson of the Scottish Mortgage Trust, one of the UK’s most consistently successful investors in the tech sector and a man who, time and again, has proved himself willing to look beyond short-term losses and back businesses seeking to build market share for the longer term.

Nor was there much effort by Deliveroo’s communications team to respond when commentators perfectly reasonably queried why shares of Deliveroo were being accorded a premium to those of rivals already listed on stock markets, such as the Anglo-Dutch Just Eat Takeaway and the German Delivery Hero, both of which have established track records.

One immediate short term risk to Deliveroo from today’s share price collapse is that it will have alienated those customers that it invited to invest. They were allocated £50m worth of shares and have immediately lost a collective £12.5m – not that they will even be able to trade their shares until next Wednesday.

The longer term risk is that an attempt to make the UK stock market more attractive to fast-growing young companies will instead have the opposite effect.