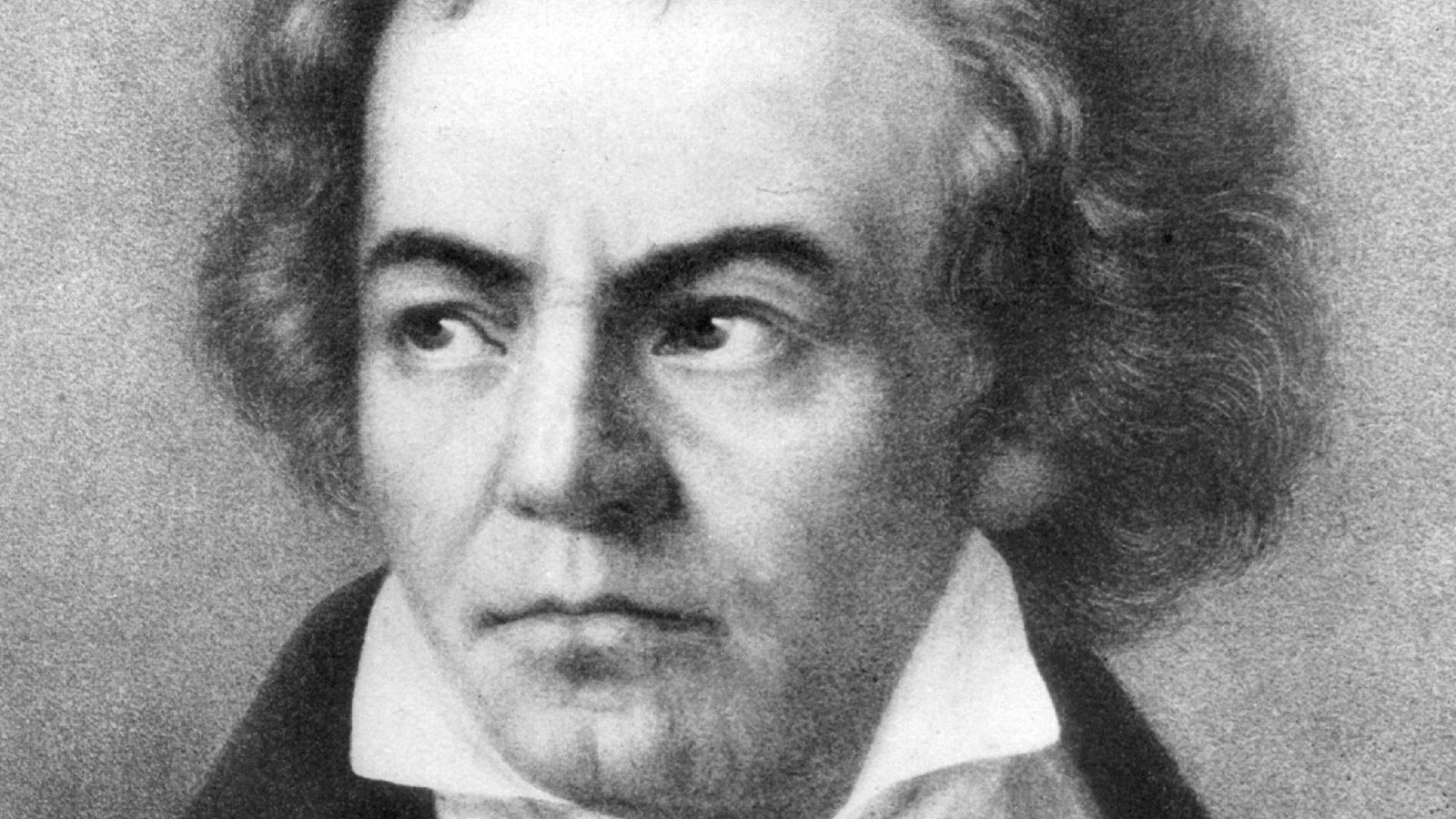

Scientists have analysed locks of what is believed to be Ludwig van Beethoven’s hair to sequence the genome of the prodigious composer – finding the likely combination behind his death at 56-years-old, as well as a potential affair in his paternal line.

An international team of researchers led by Cambridge University analysed strands of hair from eight different locks in public and private collections, five of which were deemed to be authentic and from one male European.

The German composer and pianist was born in 1770 in Bonn and began suffering from progressive hearing loss in his mid to late 20s – he was left functionally deaf by 1818. He died aged 56 in Vienna in 1827.

While unable to find a definitive cause for Beethoven’s deafness or gastrointestinal problems, the researchers’ findings indicate it is likely that a genetic predisposition to liver disease and a hepatitis B infection, combined with his broadly accepted alcohol consumption, contributed to his death.

The cause of his death has raised many questions over the past two centuries with speculation starting almost as soon as he was laid to rest.

Exposure to lead had been one of the main explanations – with some scientists suggesting that he had drunk too much cheap wine that was sweetened with lead to hide the bitterness as was the custom in the 19th century.

This was ruled out by a 2010 study, with researchers saying that a small piece of Beethoven’s skull they examined had found no more lead than in the average person’s skull.

Ukraine war – live updates: Nuclear war more likely now than ‘in decades’, Russia claims in UK uranium row

New CCTV footage released of Irvo Otieno ‘smothered to death’ by US police

Uganda set to introduce death penalty for ‘aggravated homosexuality’

‘His alcohol consumption was very regular’

Lead author of the latest study, Tristan Begg of Cambridge University, said that Beethoven’s “conversation books”, which he used during the last decade of his life, suggest “that his alcohol consumption was very regular, although it is difficult to estimate the volumes being consumed”.

He added: “While most of his contemporaries claim his consumption was moderate by early 19th century Viennese standards, there is not complete agreement among these sources and this still likely amounted to quantities of alcohol known today to be harmful to the liver.

“If his alcohol consumption was sufficiently heavy over a long enough period of time, the interaction with his genetic risk factors presents one possible explanation for his cirrhosis.”

The researchers say it is unlikely, based on the genomic data, coeliac disease or lactose intolerance were behind Beethoven’s gastrointestinal complaints.

“We cannot say definitely what killed Beethoven,” said Johannes Krause, from the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. “But we can now at least confirm the presence of significant heritable risk and an infection with hepatitis B virus.

“We can also eliminate several other less plausible genetic causes.”

Mr Begg added that, “taken in view of the known medical history, it is highly likely that it was some combination of these three factors, including his alcohol consumption, acting in concert, but future research will have to clarify the extent to which each factor was involved”.

The investigation of the hair samples did not reveal a simple genetic origin of Beethoven’s hearing loss.

Affair in lineage

The analysis of the locks of hair also found a child resulting from an affair in Beethoven’s direct paternal line which the researchers describe as an “extra-pair paternity event”.

The study suggests this event happened in the direct paternal line between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in Belgium, in around 1572, and the conception of Ludwig van Beethoven seven generations later in 1770.

“Through the combination of DNA data and archival documents, we were able to observe a discrepancy between Ludwig van Beethoven’s legal and biological genealogy,” Maarten Larmuseau, a genetic genealogist at the KU Leuven university in Belgium, said.

Mr Begg said: “We hope that by making Beethoven’s genome publicly available for researchers, and perhaps adding further authenticated locks to the initial chronological series, remaining questions about his health and genealogy can someday be answered.”

The research is published in the journal Current Biology.