In the shadow of Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th president of the United States, the Senate is set to put his predecessor on trial for high crimes and misdemeanors — potentially barring him from holding federal office ever again.

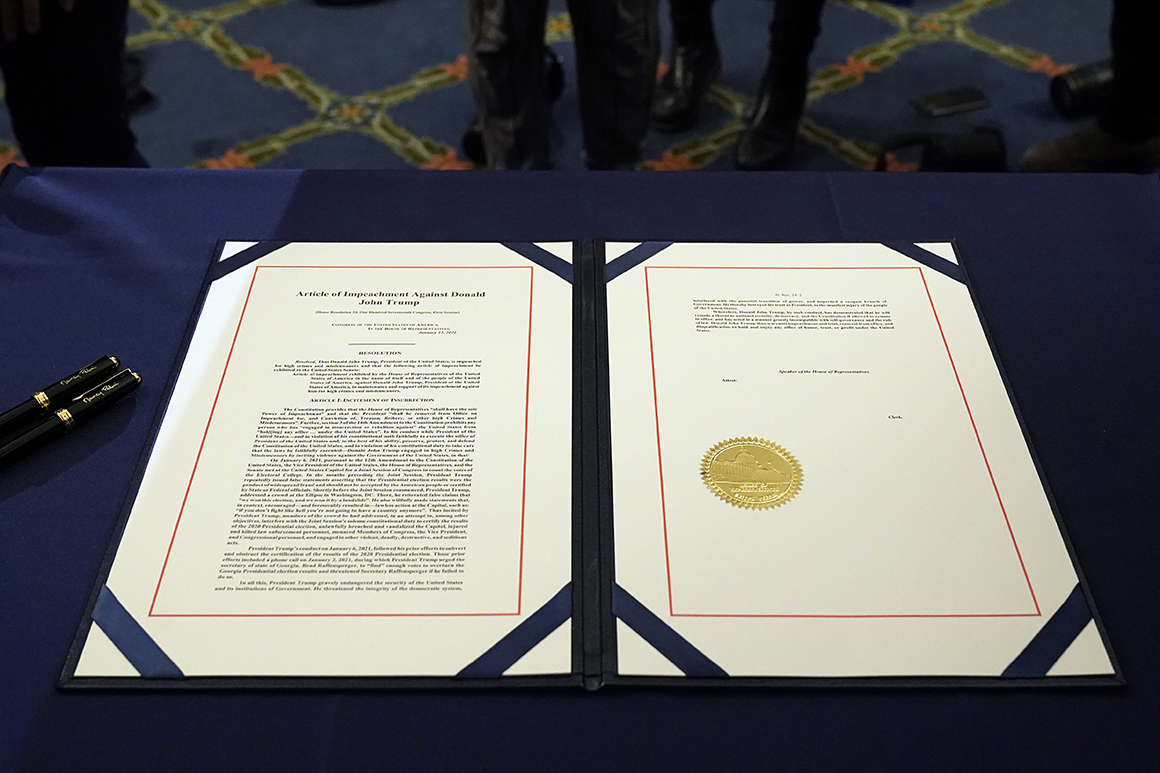

The House impeached President Donald Trump last week for “willful incitement of insurrection,” a grave charge that stems from the president’s encouragement of rioters who on Jan. 6 stormed the Capitol based on the false notion that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen.” The insurrection left five people dead and countless others injured.

The trial’s exact start date isn’t yet certain. Speaker Nancy Pelosi has not formally transmitted the impeachment article to the Senate — a move that, according to the Senate’s rules, triggers the start of the trial on the very next day. Pelosi’s deputies have said she will send the article across the Capitol “soon” but have not given a specific timeline.

Here’s everything you’ll need to know once the trial gets underway.

Can the Senate hold a trial for an ex-president?

It’s the debate that has been raging in legal and constitutional circles for a week: Does the Senate have any business deploying its most potent punishment against Trump as a private citizen?

One camp, personified by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), says no: “The Founders designed the impeachment process as a way to remove officeholders from public office — not an inquest against private citizens.” In other words, you can’t remove from office someone who has already relinquished the office.

The other view, given voice in a recent op-ed by Steve Vladeck, a University of Texas law professor, says that of course a former president can be convicted. The Constitution doesn’t just provide for removal but also for the Senate to bar that former president from ever holding federal office again. In Vladeck’s view, how could the framers have designed a “disqualification” system that could be defeated if the target simply resigned minutes before the process was complete?

The bottom line is this: Congress, by deciding to hold an impeachment trial after Trump’s exit, is daring the courts to wade into territory that judges typically avoid. The Constitution gives the House and Senate the “sole power” to handle matters of impeachment. Judges have frequently cited this to determine that they have no role in telling lawmakers how to wield their own constitutional power. It’s safe to think they’ll end up there again.

Will the 2021 trial work differently than last year’s?

A year ago, Congress spent the first full day of Trump’s impeachment trial in a fierce battle over the rules, which dictate the entire course of the trial. Back then, conviction was a nonstarter — most Republican senators had pretty much ruled it out from the start, and the major questions were how uncomfortable Democrats could make them before they summarily let Trump off the hook.

This time, with a slew of undecided senators — including Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the outgoing majority leader — the rules loom even larger.

One thing to watch for: Do Republicans like Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), who oppose the trial, try to force a vote on dismissing the charges? If they do, it will probably fail since the Senate will be split 50-50 along party lines, and enough Republicans have signaled openness to conviction that they’re unlikely to end the trial before it begins. But that vote could also be an early test for just how many Republicans might be open to conviction.

After sweeping aside any dismissal attempt, the Senate must determine how much time to give each side to lay out its arguments. In 2020, it was 24 hours apiece. Seven House impeachment prosecutors and a team of veteran White House and constitutional lawyers spent six days offering their cases. This time, Pelosi has selected nine impeachment managers and Trump hasn’t even identified a legal team to deliver his case.

Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), the lead impeachment manager, has not tipped his hand on specific strategies, but he has offered this broad exhortation: “We just want the Senate to conduct a serious trial where every member of the Senate lives up to his or her constitutional oath to render impartial judgment as a juror.”

One unusual aspect of this trial? Every impeachment manager and every juror was also a victim of the alleged crime: incitement of insurrection. The same people trying and deciding the case were the ones ducking behind chairs and dodging violent mobs less than two weeks ago, while they frantically pleaded with Trump for help that only belatedly arrived.

Raskin intends to lean on that experience as he tells a big-picture story about the insurrection as an “attack on our country.”

“There are thousands of people that work on Capitol Hill, not just members but staff members, and Capitol Hill police officers, who were pushed and shoved and punched in the face, pummeled and hit over the head with fire extinguishers,” Raskin said Sunday on CNN’s “State of the Union.” “And the president did nothing to stop it for more than two hours as members of Congress called him and begged him to do something and he continued to watch it on TV and enjoy their insurrection tailgate party.”

Democrats will also point early and often to the arguments lodged by the 10 Republicans in the House who voted to impeach Trump, including Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, the No. 3 House Republican.

Last time, Democrats also sought to empower Chief Justice John Roberts — required by the Constitution to preside over presidential impeachment trials — to decide matters of executive privilege. But Republicans rejected the suggestion, and Roberts himself signaled he intended to play a low-key role.

How likely is a conviction?

Make no mistake about it: The House impeachment managers face an uphill climb as they try to persuade enough senators to vote in favor of conviction. Last year, there was virtually no chance that the Senate would reach the two-thirds threshold required, but this year, it seems at least possible that at least 17 Republicans could join all 50 Democrats to vote to convict.

For starters, McConnell has adopted a markedly different posture. Ahead of the last trial, McConnell said there was “no chance” Trump would be booted from office and was a key defender of the president. But this time around, McConnell is keeping an open mind and is urging his fellow GOP senators to keep their powder dry. It could mean that Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, the only Republican who voted to convict Trump in the first impeachment trial, will have company this time around.

Trump’s exit from the White House alone isn’t likely to be a good enough reason for Republicans to feel comfortable with voting to convict him. Even though the president will be out of office by the time the Senate votes on conviction, he will remain a force within the GOP for years to come, and he has pledged to remain involved in campaigns. A chief concern for Republicans facing reelection in 2022 and 2024 is that Trump could back a primary challenger.

Still, convicting Trump and barring him from holding federal office could clear a pathway for the countless Republicans considering seeking the GOP presidential nomination in 2024, many of whom serve in the Senate. If Trump decided to run for president again in 2024, he could be the favorite to secure the party’s nomination.

McConnell will be the most important person to watch in determining whether the Senate has the votes to convict Trump. If he votes “yes,” it’s easy to see at least 16 other Republicans joining him. If he doesn’t, conviction becomes much less likely.

Will the House managers attempt to call witnesses?

At last year’s trial, Democrats were pressing vigorously for the Senate to hear testimony from additional witnesses who could shine light on Trump’s alleged misconduct. But this year, it might not be in Democrats’ interest to push for witnesses.

Democrats have raised concerns about holding a trial in the opening days of Biden’s presidency because it would delay Senate action on staffing his Cabinet and considering additional Covid-19 relief legislation.

At the same time, with so many Republicans appearing open to conviction this time around, it might be beneficial for the House impeachment managers to be able to call witnesses, especially because the House did not conduct a formal impeachment inquiry before last week’s vote.

For now, the House impeachment managers are remaining mum about their strategy when it comes to witnesses. Democrats have maintained that a full investigation is not necessary because the evidence for impeachment is in the public domain — and lawmakers themselves were witnesses to an insurrection that put their lives in danger.

“The last [impeachment trial] was information brought to us by others,” said Sen. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, the No. 4 Senate Democrat, in an interview. “This is an impeachment based on what we experienced, and what the president of the United States said, in speeches, that day, that were videotaped. All the evidence is really right in front of us.”

Indeed, senators themselves were forced to hastily evacuate the Senate chamber and were just feet away from the violent mob that eventually made its way onto the Senate floor. During last year’s trial, the House managers used several audio and video clips to aid their legal arguments; this year they’re likely to use to their advantage the hours of troubling footage showing the rioters desecrating the Capitol, violently beating police officers and rummaging through the Senate chamber — in addition to clips of Trump’s remarks ahead of the storming of the Capitol.

One potential witness on Democrats’ list is Brad Raffensperger, the Georgia secretary of state. Trump has mercilessly harangued Raffensperger and Gov. Brian Kemp, who are both Republicans, for not adopting his unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud in the state. Earlier this month, the president held an hourlong phone call with Raffensperger during which Trump pressured the secretary of state to “find” votes on his behalf to overturn Biden’s victory in Georgia.

Prosecutors in Atlanta are reportedly considering opening a criminal investigation into Trump over his pressure campaign.

Still, Democrats might reject outside witnesses in the name of completing the trial more quickly.

“We have so much to do,” Stabenow added. “There’s no reason to spend time that isn’t necessary. We need to follow the law and the Constitution, treat this with seriousness. And the process needs to have integrity. At the same time, we need to have it move along in a way that will allow it to be completed so that we can continue the other critical things that have to get done for the country.”

Disarray on the president’s legal team

In previous years, a chance to represent presidents would be a lawyer’s dream, a crowning career achievement that could also mean lucrative professional opportunities in the future. But Trump has proven to be a difficult client and, in this case, a toxic one. Few appear to be lining up to eagerly combat charges that the president — through a monthslong campaign of false and pernicious claims of election fraud — motivated the frothing Jan. 6 mob to attack the Capitol and hunt down Pelosi and Vice President Mike Pence.

In 2020, Trump recruited former independent counsel Ken Starr and Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz to mount big-picture legal arguments, which were effective with some open-minded senators. He also had veteran White House lawyers Pat Cipollone and Patrick Philbin at the defense table, along with outside counsels Jane and Marty Raskin, former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi and conservative lawyer Jay Sekulow.

This time, none of the same attorneys appear poised to return. Dershowitz has indicated he generally supports the view that Trump’s Jan. 6 remarks to the rally crowd, which later became the violent mob, are protected free speech. But he has indicated he will probably make those arguments from the sidelines this time.

That has left Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani — whose own efforts to aid Trump’s campaign to overturn the election have drawn bipartisan scorn on Capitol Hill — as one of the only prominent figures standing in Trump’s legal defense orbit. But reports suggest that Giuliani has also been ruled out. Over the weekend, Trump campaign spokesman Hogan Gidley said Trump had simply not decided on an impeachment legal team yet.

Burgess Everett contributed to this report.